Why Vanguard likes BHP

Summary: Jamie Horvat, co-manager of Vanguard Precious Metals & Mining, doesn't really care where the price of gold is heading. That's because the fund isn't a pure play on the price of gold, or even gold miners. While three quarters of the fund is in precious metals miners, the remainder is made up of diversified base-metals miners – such as BHP – to minimise volatility. |

Key take-out: The fund's 6 per cent stake in BHP is its third-largest. BHP's $114 billion market value is much larger than even the largest gold miners, making it less sensitive to swings in any market. It also makes it the largest by far in the fund, which, even including BHP, has an average market value of just $3.2 billion. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors Category: Shares |

Ask Jamie Horvat, co-manager of the Vanguard Precious Metals & Mining fund, where he thinks the price of gold is heading, and he's quick to tell you: “I don't really care.”

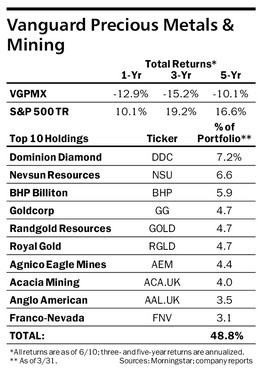

Horvat joined the $2.1 billion fund (ticker: VGPMX) in 2014, right after the price of gold tanked, falling 29 per cent, from $US1,692 an ounce at the beginning of 2013 to $US1,202 by the end. That same year, 2013, the fund lost 35 per cent. That sounds bad, but that 35 per cent loss made Vanguard Precious Metals & Mining the best-performing fund in the category, according to Morningstar.

Today, gold is even lower, at $US1,180 an ounce. But Horvat, 43, isn't worried. When pressed, he says that gold prices won't fall much further and, in fact, could even rebound. The European Central Bank and that of Japan are printing lots of money in an effort to stoke inflation. That will probably have two effects. One: It will increase demand for gold, which has long been purchased as a long-term hedge against the declining purchasing power of money. Two: Higher inflation means that the cost of raw materials increases. As the costs related to extracting and producing the metal rise, some poorly managed miners will struggle to be profitable and may even cease production. Those miners will have the same struggle if gold prices drop below $US1,100 an ounce. Either scenario leaves a bigger opportunity for the miners that can withstand lower gold prices and a higher cost of capital.

Horvat grew up in Canada, where natural resources were essentially the national industry. He once worked for a forestry-equipment company, and his brother was involved in mining. Now, along with co-manager Randeep Somel, Horvat works for M&G Investment Management, the London-based firm that subadvises the Vanguard fund. The two replaced Graham French, who managed the fund from 1996 through 2013 via M&G, and is largely responsible for the fund beating 62 per cent of its peers over the past 15 years. The fund's recent performance is even more impressive; its 15 per cent loss over the past three years beats 99 per cent of its peers; it's eking out a 2.4 per cent gain so far this year, putting it in the top quartile of its category.

Horvat has focused on the natural-resources and mining industry since 2004, when he managed a stable of resource funds for AGF Management. He then went on to manage some of Sprott Asset Management's portfolios from 2008 to 2012, including its gold and precious-minerals fund, traded only in Canada.

Vanguard Precious Metals & Mining is not a pure play on the price of gold, or even gold miners. Today, about three-fourths of the 49-stock fund is in precious-metals miners. That's up from 50 per cent under French's tenure. Horvat and Somel include diversified base-metals miners—such as BHP Billiton (BHP), which produces iron ore, copper, oil, and gas—to minimize the portfolio's volatility. BHP's performance isn't correlated with gold prices; it moves more in line with the broad market, which tends to rise as gold prices are falling.

The fund's 6 per cent stake in BHP is its third-largest. BHP's $114 billion market value is much larger than even the largest gold miners, making it less sensitive to swings in any market. It also makes it the largest by far in the fund, which, even including BHP, has an average market value of just $3.2 billion.

Horvat is focused on companies with good, conservative management. As gold prices rose steadily from 2001 through 2011, many gold miners overspent when developing new deposits. Today, Horvat looks for companies whose cost of production can withstand gold prices falling below $US1,100. That would allow them to maintain profitability even if gold prices fall another 10 per cent. “The mining industry forgot that it was cyclical,” Horvat says.

Miners' ebullient overinvesting began when gold prices began rising after the 20-year bear market from 1980 through 1999, he adds.

Mining is pricey work, and Horvat wants to see that a company can cover the cost of its capital even when commodity prices are not at their highest. For instance Randgold Resources (GOLD), a $US6.6 billion gold-mining company focused on sub-Saharan Africa, has long used conservative assumptions when developing ore deposits that allow it to earn much more than the cost of capital, Horvat says.

Specifically, he says chief executive Mark Bristow insists that an ore deposit must be more than three million ounces and have the potential to yield profits of at least 15 per cent a year when using conservative (usually below market) assumptions of gold prices—today, that would be $US1,000 an ounce.

Horvat adds that Randgold generates return on the capital employed of 6.8 per cent in a sector where other gold miners average a return of negative 8.9 per cent.

“That's the type of company you want to be aligned with,” says Horvat. And he's aligned with it by devoting 4.7 per cent of the fund to its stock.

Another top holding is $14.1 billion Vancouver-based precious-metals miner Goldcorp (GG), which has mines across the Western Hemisphere. Horvat likes its history of buying mines or mineral deposits at the bottom of the cycle and selling at the top. For instance, Goldcorp sold the San Dimas and Escobal mines in 2010, when silver was trading at more than $US30 an ounce. It has since fallen to less than $US20.

Horvat also points to Goldcorp's purchase of Virginia Gold's Éléonore deposit in 2006, when gold was just around $US620 per ounce, about half of where it is today.

Horvat says Goldcorp's shares are inexpensive relative to others in the peer group. Its stock trades at eight to 10 times annual cash flow, versus the 12 to 17 times for its peer group of precious-metals miners.

Toronto-based precious-metals miner Agnico Eagle Mines (AEM) has a history of developing deposits into mines with very long operating lives. Horvat points to its Pinos Altos mine in Mexico, which first started producing gold in 2009 and is expected to keep going through 2018. The company has consistently paid dividends for 32 years.