Why this is a bad time to win an election

Kevin Rudd came to power for the first time on December 3rd 2007, just a few months after the global financial crisis commenced, and some time before its severity was truly appreciated by the political classes of any nation. On September 7, he lost office for the last time.

The first election he won was a bad one to win, not because he was blamed for the calamity of the GFC itself of course, but because his entire term was dominated by reacting to it.

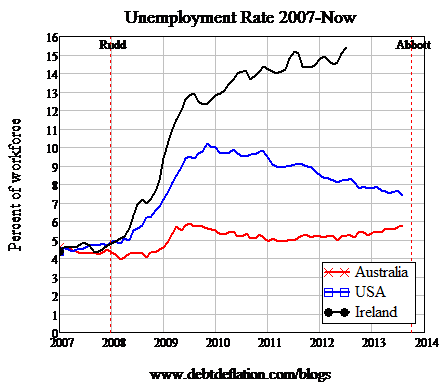

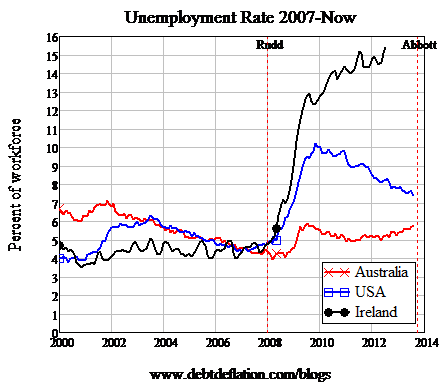

That reaction had parts that could be rubbished (everything from the Liberal Party’s favourite farce of the Pink Batts program to my pet hate, the First Home Vendors Boost) but a simple comparison of Australia’s economic performance to that of the rest of the OECD over the last six years shows that his reaction worked – see Figure 1, which shows unemployment in Australia, the US and Ireland. Unemployment never exceeded six per cent here, and growth turned negative for only one quarter. The US, on the other hand, had its longest post-war recession ever, and Europe’s obsession with austerity turned its downturn into a genuine second Great Depression.

Figure 1: Australia handled the GFC much better than the US or Europe

Of course, though Rudd had bad luck to take over when this crisis was just beginning, he also had good luck on his side as well – not least that our biggest trading partner undertook an even bigger government stimulus in response to the crisis that gave us the best terms of trade in our history, and our biggest export boom.

So could this election be a good one to lose? Not for Rudd, of course. Surely there’s no way he will emulate “Lazarus with a triple by-pass” and make a comeback from this electoral defeat. But the ALP will hand over the reins of government to the Liberals at much the time that luck is no longer playing on the Australian side. If so, this will be unusual, since normally timing has played into the Liberals' hands rather than Labor’s.

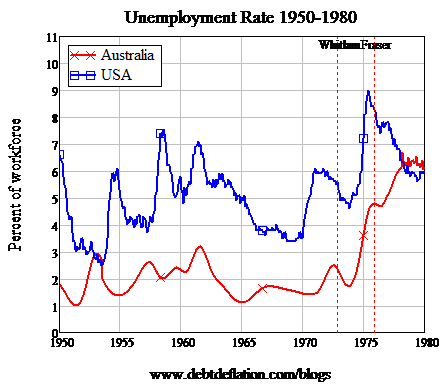

Gough Whitlam’s victory over William McMahon in December 1972 took place at the beginning of one of the last booms in Australia’s generally booming Post-WWII economy. It will be hard for readers under 60 years old to appreciate this, but the average unemployment rate in Australia from 1950 till 1972 was below two per cent. However, shortly after Whitlam took power, the boom gave way to a huge bust.

The deterioration of the economy then was blamed on the Whitlam government’s policies, but the evidence is clear that he simply had the misfortune to come to power just when the long post-war boom was unravelling. As Figure 2 illustrates, however much Whitlam might have been ridiculed locally for the Khemlani affair and the like, the collapse in economic growth and the rise in unemployment during his term was a global phenomenon. His problem wasn’t bad economic management, but simply bad timing.

Figure 2: The downturn blamed on Whitlam was a global phenomenon

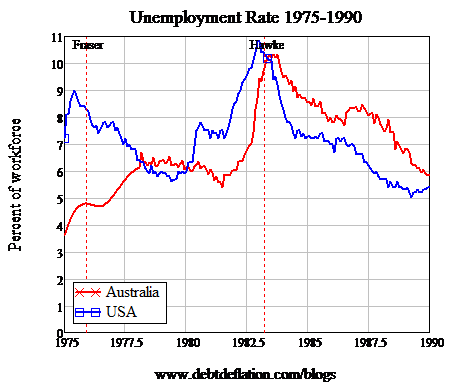

Malcolm Fraser, on the other hand, was the one post-war example of a Liberal leader taking over from a Labor one at an inopportune time. The Liberals won that election on the basis that they were better economic managers than Labor – “just look at the evidence!” – but history shows that it was simply bad timing for Labor that was followed, on the surface at least, by bad policy by Fraser’s Liberals. Unemployment continued to get worse under Fraser (with Howard as his Treasurer), despite his very different approach to economic policy to Whitlam (and Jim Cairns), and this bad performance on unemployment was the opposite of what happening in the US at the time.

Hawke, on the other hand, took over from Fraser at almost the perfect time internationally. He and his “world’s greatest treasurer” Paul Keating could bask in the success of their economic policies, but again the Australian performance at the time largely mirrored what was happening in the US when Ronald Reagan was in the White House, and followed a very different political and economic agenda to Hawke and Keating (see figure 3). It was the politician’s timing that mattered once again, far more so than the politician’s policies.

Figure 3

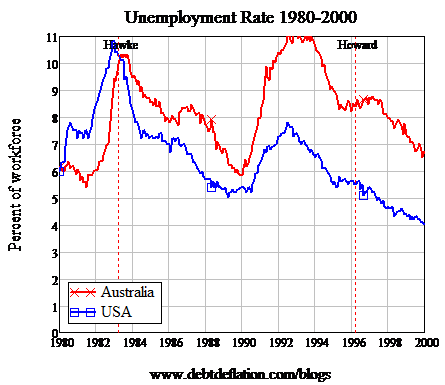

Ditto John Howard when he downed Paul Keating. By then, Australia had recovered from “the recession we had to have”, and the economy was improving in both Australia and the US, despite the fact that one country now had a conservative government and the other had Bill Clinton’s Democrats in power (see figure 4).

Figure 4

Then along comes Rudd, and though yet again timing far more than his policies dictated the economic circumstances of the day, the undeniable fact is that Australia’s economic performance diverged from that of the rest of the world (see figure 5). Rudd’s policies – or rather those proposed by his Treasury Secretary Ken Henry of “Go early, go hard, go households” that Rudd adopted with gusto – worked.

Figure 5

So if – with the sole exception of Rudd – it wasn’t the policies of politicians that determined the fates of their economies, what was it?

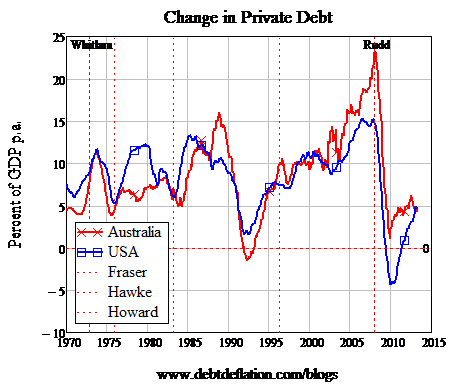

It was their timing relative to the global debt bubble that has determined the fate of Western economies ever since the early 1970s (see figure 6, which shows the rises and falls in the rate of growth of private debt in Australia and the US since 1970).

Whitlam had the great misfortune to come to power six months before the first popping of the bubble in mid-1973. Rudd was even unluckier; his first term began literally when the global recession commenced as the debt bubble had its biggest pop in history.

Fraser was, in some ways, the unluckiest of all: he came to power after the 1973 bursting of the debt bubble, but whereas the US then had another debt-driven revival, Australia didn’t. So the economy languished under him, not because of his policies (which were largely irrelevant), but because debt growth took a lot longer to rise again in Australia than it did in America after the 1973 crisis.

Hawke and Howard, on the other hand, had the fortune to come to power as the debt engine started revving again.

Figure 6: Riding the waves of the private debt bubble

So what could the future hold for Prime Minister Abbott? Here I have a hunch that he’ll end up suffering a similar fate, not to the previous Liberal leader he admires – John Howard – but to one I expect he detests – Malcolm Fraser.

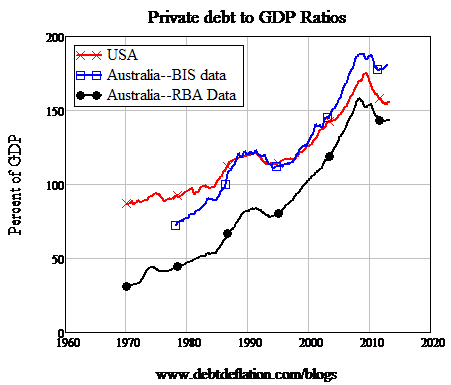

Fraser, as noted, had the good fortune to take over from Whitlam after the bursting of the debt bubble was largely over, but the bad fortune that the revival in Australia's bubble was considerably more anaemic than America’s. Abbott could well find himself experiencing a similar double-edged sword of fate. He will take over when the deleveraging that caused the GFC has come to a temporary halt, and demand will be rising in the US (and maybe even in Europe, from the depths of its self-imposed Depression) thanks to rising private debt (see figure 7). But this rise could peter out even more quickly than it did for Fraser, leading to anaemic economic performance that will be blamed on the politician rather than the times.

Figure 7

Australia also faces the headwinds of a possible bursting debt bubble in China, something that is also beyond Abbott’s control. Our new prime minister may find that he lives in interesting times, rather than favourable ones.

For a different take on the economic circumstances our new government faces, read today's article from Stephen Koukoulas: Abbott stumbles into a surplus of luck.

Steve Keen is author of Debunking Economics and the blog Debtwatch and is developer of the Minsky software program.