Why crude oil plunge won't last

| Summary: The shale boom is unlikely to spur a sustained a fall in the crude price, but there won’t be a price surge either. Global crude production, or the momentum behind it, isn’t expected to change materially over the next year. |

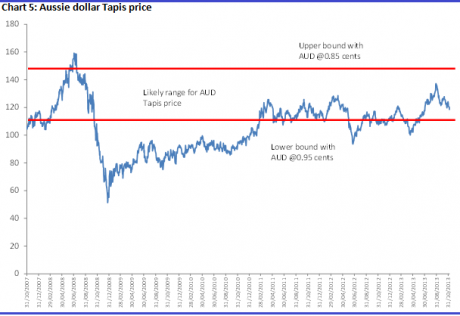

| Key take-out: From an Australian perspective, the US dollar exchange rate will be the primary determinant of crude prices. If the Reserve Bank is successful in bringing down the currency to 0.85 cents, this suggests an upper bound for the AUD price of oil at around $145 – or 22% higher than today. |

| Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Commodities. |

Reading the mainstream coverage of the shale boom in recent times you might be forgiven for thinking the recent slump in oil prices is the start of a trend.

What’s more, you might also be led to believe the US ‘shale boom’ is set to become a game changer for the wider oil market … and as this happens the rest of the world gets a brake on inflation. Sorry, but it simply does not stack up.

Since a recent peak in early September (that’s a cyclical peak … the theory of a permanent ‘peak’ has been put on the shelf for the moment), crude prices have tumbled nearly 14% on West Texas Intermediate, while Brent is down nearly 10%. Big moves, seemingly at odds with the macro data out from China, the US, Europe - and elsewhere - showing a solid acceleration in growth.

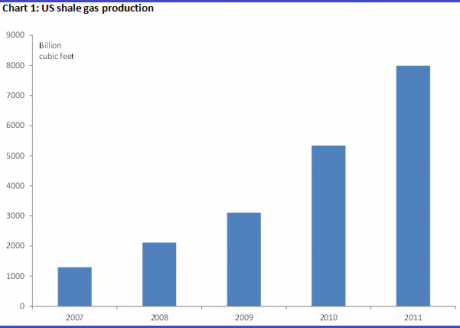

Now obviously, and many of you would have already said this, shale is quickly pointed to as the explanation for the divergence. And you can see why when you look at chart 1 below. Whether oil or gas, the shale ‘revolution’, underpins forecasts for the crude price to fall another $US20 or even more which would see WTI average around $US60-70 over the next year, Brent $US85.

The impact on the globe, if that did indeed occur, would be profound in two senses. Firstly, it would effectively amount to a major stimulus for the global economy. Think much lower energy bills – transport, electricity, heating, the lot. That, in turn, would provide a decent lift to industrial margins, not to mention the secondary effects that flow on to other areas – retail and the like.

It would also provide a significant disinflationary force. In an environment where the Fed, and the European Central Bank, are already worried that inflation is too low – sub 1% – it would almost certainly rule out a taper in 2014. Indeed, it may instead see the US ramp up the printing presses. The ECB has already provided more stimulus and promises to pump more cash into the economy in 2014.

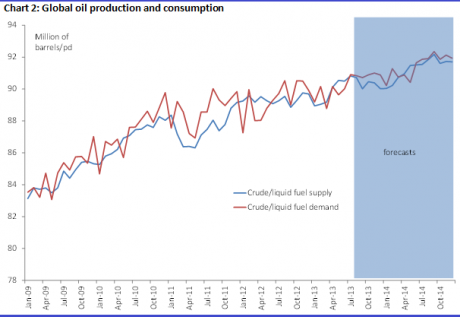

We’re obviously at a critical juncture, and the debate is a furious one. Matt Mushalik made an interesting point last week (click here) that the US, despite the shale boom, will likely remain a net importer of oil for some time. By itself, that would seem to argue against this idea of an imminent price slump. I’d probably add to his point, that while the rapid growth in shale gas/oil production may be a boom for that specific area, and perhaps the US more broadly, it doesn’t appear that shale gas/oil production is providing some sort of overall petroleum/gas oil boom to the globe. You can see this in chart 2 below.

As you can see, global crude production, or the momentum behind it, isn’t expected to change materially over the next year. There is no oil or natural gas glut as such, despite the shale boom, and the chart even shows that demand for liquid fuels including crude and gas, is still expected to outstrip supply. The world consists of more than just the US and its shale. Moreover, I’m not seeing too much difference in the long-term forecasts either – out to 2035 or 2040. Energy demand, for instance, is expected to rise by one third over the next two decades, according to the International Energy Agency. Yet, what is apparent in those forecasts is the diminishing, though still significant, role expected to be played by liquids such as crude and gas. A growing energy gap that will be met, not by shale, but rather nuclear fuels, renewables and coal.

How is that possible given the shale boom and such strong growth rates of production in that space? It’s a simple measurement difference and one between growth rates and absolute levels. The percentage change, or growth rates of shale oil/gas production are truly impressive – and it is a boom in that space. Yet, in absolute terms, and measured on a like-for-like basis (in this case barrels instead of cubic feet) the impact is less dramatic. Refer to chart 1 again at this point and after that, take a look at chart 3 below for another perspective.

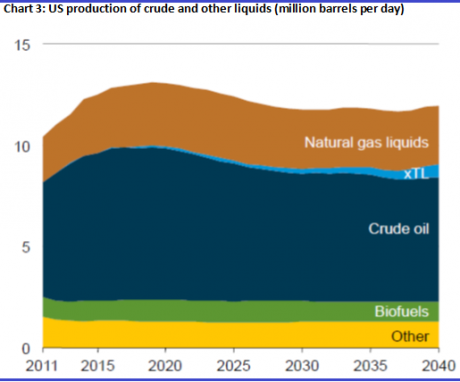

That five-fold increase (433%) in shale gas production you saw in chart 1, a real revolution for shale, really only equates to about 2 or 3 million barrels per day in total liquid fuel production for the US. So production goes from about 10 million barrels per day in 2011, peaks at about 13 million barrels per day by about 2020, before declining to 12 million barrels per day.

That’s all good and well, except that the US consumes closer to 20 million barrels per day – and thus Mushalik’s point that the US will remain a net importer is right on the US government’s own numbers. More broadly, the world consumes about 90 million barrels per day. With that in mind, to talk of shale as some revolution in the production of energy, for the globe, is not quite right in my view.

It’s also important to consider that forecasts for energy consumption, by the EIA and others, are almost certainly on the light side. The EIA forecast average growth of 1.3% per year over the next 30 years or so, down sharply from 2.5% per year over the last decade and 2% since 1980. Technology and the continued development of the emerging world ensures that forecast is going to be wrong. The issue then has been, and will remain, one of scarcity. How does the world provide for its growing energy needs with finite resources? The answer at this point doesn’t appear to be shale.

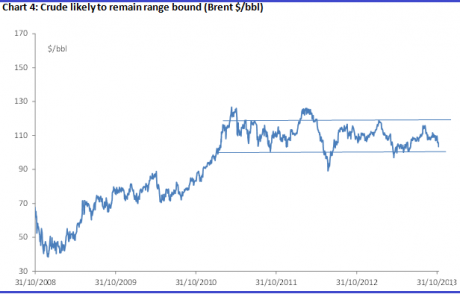

To my mind, the consequences of that a twofold. Firstly, we are unlikely to see a sustained a fall in the crude price – certainly not much below $US90. There is clearly no glut of oil or shale although, and as I’ve warned in a number of pieces since (see for instance my July 26, 2013 piece A red flag for commodity investors) neither are crude prices likely to surge – which had been my prior expectation.

That suggests to me that crude is unlikely to break out of its range – the range we’ve seen for the last three years. For WTI the lower bound of that range has been around $US85, that’s $US8-9 more downside from here although it’s never there for long. For Brent, things may be a little more stable – about $US4 or $US5 downside according to the charts.

From an Australian perspective then, that still leaves the exchange rate as the primary determinant of crude prices. If the Reserve Bank is successful in bringing down the currency to 0.85 cents, then my analysis suggests an upper bound for the AUD price of tapis at around $145 – or 22% higher than today, with a lower bound of around $108.

In the early stages of the GFC recovery I had expected a surge in crude, or commodity prices more generally, that would provide the link between low interest rates/QE, surging asset prices and then consumer prices. With that link now severed to some degree, consumer price inflation is now going to be much more subdued than I had initially thought - as I have outlined in other pieces.

The second consequence of my analysis on shale and the crude market, is that we are probably not witnessing a major disinflationary impetus. It’s true to say, for instance, that Eurozone inflation is well below target now, at an annual rate of 0.7%. Indeed the European Central Bank surprised some observers with a .25% interest rate cut this week. But remember it was only a year ago that inflation was well above target. The major change over that period was the sharp drop in energy prices, which according to the European statistics agency, fell from an annual growth rate of 8% a year ago to -1.7% now.

That being the case, and if I’m right on the above, inflation results will be volatile, but it’s highly unlikely that disinflation will take hold.