Why Australian house prices are cheap

Summary: Australian property remains cheap compared to other nations despite comparatively high urban concentration, data provided by the McKinsey Global Institute shows. In fact, while debt is already high in Australia, international experience tells us there is no reason why it can't push higher, particularly when three quarters of our household debt is being held by top income earners. |

Key take-out: As always, detached housing is a better investment than in units, particularly in Sydney where there is no sign of a pick-up in construction. If you're nervous about Sydney and Melbourne, there are good opportunities elsewhere. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors Category: Property. |

The discussion on residential property has become highly emotional and most of it has detached from any sensible analysis. The problem is that most commentators simply can't fathom why we haven't had a house price slump. It's that frustration, rather than any rigorous analysis, that underpins repeated negativity on property as an investment. Those calls were, and are, based on a fundamental misunderstanding of economics – flawed assumptions.

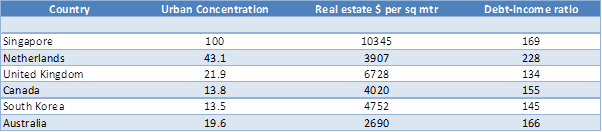

Table 1 below should dismantle most of the arguments used against property. It's based on data provided by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI). It shows real estate prices per square metre (adjusted for purchasing parity disparity), debt to income ratios and urban concentration in large cities (around 3 million) as a percentage of total population.

Table 1: Is Australian property actually cheap?

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

The table tells us a few things, but what really stands out is just how cheap property is relative to other nations – despite the comparatively higher urban concentration in Australia in some cases. Not as high as the Netherlands or Singapore, but it is high. Higher than Canada and a number of other countries. Common sense tells us that the higher the urban concentration, then the higher property prices should be – all else equal – and this is indeed what MGI generally finds.

The fact is there's a major long-term support for the property market, even with already high debt levels. That's because, while debt is already high in Australia, international experience tells us there is no reason why that can't push markedly higher. Look how high the debt ratio is in the Netherlands – 228 per cent – or Singapore. There are a number of countries that have household debt to income ratios well over 200 per cent, including Denmark and Norway. In the latter, house prices have still managed to punch up 30 per cent since the GFC, even as the debt servicing ratio fell 5 per cent.

That shows that household debt simply isn't the big constraint some think it is – the actual experience of property prices around the globe tells us this. The analysis is much more complicated than simply looking at one ratio and drawing conclusions from that. Which is what a lot of commentators do – even the RBA does it.

You see a lot depends on who, exactly, is actually taking on the debt. In the US it was lower income earners – that's why they had a crisis. In Australia and some of the European countries mentioned above, debt has predominantly been taken up by high income earners or those with high net wealth. Indeed, the top 20 per cent of income earners hold nearly half the total of household debt. The next 20 per cent hold another quarter. So 75 per cent of household debt is held by the top income earners. That's not a big problem and it's not impediment to further house price growth.

In any case, take a look at how monetary policy is being run in Australia and around the world. It is actively accommodating existing high debt levels and is even encouraging debt levels to rise. This is how monetary policy works. It will always accommodate the existing level of debt and act to the push that higher through the business cycle. So in the Australian context, if non-mining investment doesn't pick-up, the RBA will simply act to accommodate even more debt.

The fact is that property remains a great long-term investment and there is little risk of a US style bust. The conditions – the laws we have in place – are completely different. That's not to forget that the fundamentals remain very supportive. The unemployment rate has been stable at around 6.2 per cent for over a year now and even that is likely an overestimate. Otherwise, interests rate remain low and the economy looks to be accelerating, notwithstanding the slump in investment we saw last week.

That's not to say that property doesn't still have a cycle – it does – but within those cycles, the long-term prospects for Australian property prices are very strong. I'm not saying this is socially desirable or good policy. The cold hard facts remain though; property is and will remain a very good long-term investment in this country and its important – and profitable – to recognise that against what has become a very emotive and irrational discussion.

The landscape has changed though. Price gains in Sydney have been remarkable, rising about 45 per cent over the last three years or so. In Melbourne, price gains are lower but still impressive at 18 per cent. Elsewhere, gains have been more modest, but there are growing signs of life. That is, price growth is spreading in Australia's three-speed housing market.

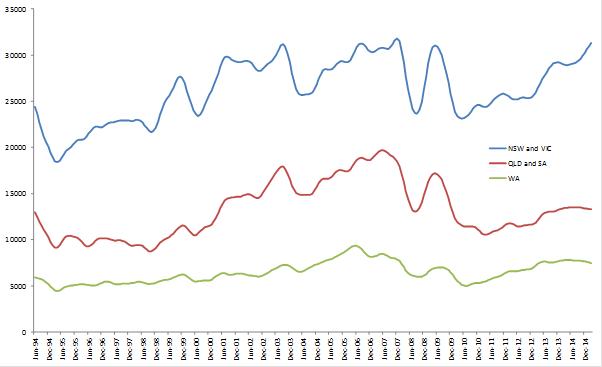

Chart 1: Australia's three speed property market – by lending

You can see this best in the lending figures. Lending in NSW and Victoria has been strong as you'd expect, especially in NSW. The thing is, while lending has also been on an upward trajectory to a smaller extent in Queensland and South Australia, it's still been there.

It's been slower, more hesitant, but there has been good reason for that. Take Queensland – where job insecurity had been extreme and confidence low. That looks to be turning on recent indicators – especially consumer spending figures. Queensland consumers actually look to be leading the national rebound in spending that we've seen so far. Annualised spending over the last quarter is over 9 per cent, which compares to the national average of 6 per cent.

Queenslanders are obviously feeling much more confident about things and that will feed into the property market. The Brisbane market has already been performing quite well and that looks set to accelerate. If you're nervous about Sydney and Melbourne there are still good opportunities within the city of Brisbane. Especially as housing construction across the Queensland capital is still inadequate to deal with strong population growth.

Otherwise it might be worthwhile looking at some of the major regions. Data from Core logic shows that rental yields in some of these areas are attractive – not to forget the solid capital growth in some instances as well. This is another sign that the positive forces hitting the Sydney and Melbourne property markets is starting to be felt elsewhere.

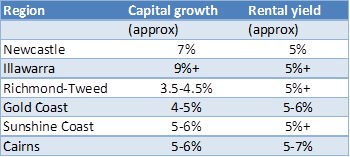

Table 2: Attractive capital growth and rental yields in regional centres

The table is only a sample, but with total returns on offer are of between 9 and 14 per cent there are clearly opportunities that investors could explore given the very positive fundamental backdrop.

As always, detached housing remains a better investment than units – especially in Sydney where it remains a fantastic investment – for the simple reason that there is no sign of a pick-up in construction. The surge in national approvals is mainly apartments and demand for detached housing far exceeds supply. That's an important development given about 70-75 per cent the existing dwelling stock is still detached housing.