The three forces pushing Australia towards recession

Rampant speculation in the Australian and Chinese property sectors leaves our banking and mining sectors vulnerable to collapse within the next three years. Toxic lending and short-sighted policy have left us poorly placed to handle an economic shock, particularly if it originates in China.

These are the startling views featured in a recent book by former strategy consultant, Lindsay David, in Australia: Boom to Bust. I sat down with David to discuss his book and the broader implications of Australia’s rapidly rising indebtedness, and China’s obsession with property investment.

According to David, the Australian economy is set up around three central pillars: banking, real estate and mining. During the good times -- and with the support of China -- this set-up has proved conducive to strong economic growth, with Australia experiencing a post-war boom that is unprecedented among developed economies.

For 23 years we have, indeed, been the lucky country. But all good things must come to an end.

Australia’s property market has boomed since the mid-1980s -- though in more recent times it has been far more cyclical. Australian banks have binged on mortgage lending, reaping record profits year after year, which has resulted in one of the highest levels of private debt in the developed world.

David’s assessment of Australia’s banking system is startling and uncomfortable reading for those who believe that our major banks are well capitalised and prudent lenders.

Our major banks are huge by international standards; three of the four are currently among the biggest 20 banks in the world for market capitalisation. All four sit among the world’s top 40 banks for total assets.

They are also among the most leveraged financial institutions in the world. Most of that lending has been directed toward mortgages -- debt that is commonly considered to be relatively safe but also does little to add to the productive capacity of Australia.

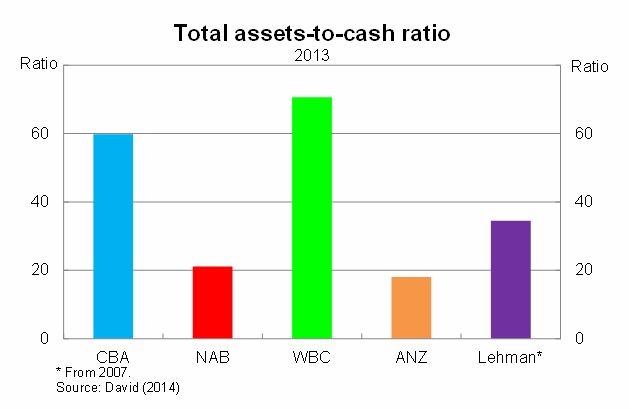

Australian banks have completely embraced the Lehman Brothers model, highlighting just how little they and policymakers have learned from the global financial crisis. In 2013, Australian banks held relatively little cash compared to their more risky asset holdings.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers -- which had assets worth around 5 per cent of US GDP -- almost brought the global financial system to a standstill. Crisis measures were required to stop most major US banks collapsing. The recovery is in its sixth year and counting.

By comparison, the Commonwealth Bank has assets worth almost half of Australia’s GDP and the other three majors are of similar size. Since their balance sheets are so similar, with regard to total assets and exposure to mortgages, they largely operate as a singular entity. A crisis that hit one bank would immediately spread to the other three.

Could the federal government or the RBA really afford to bail out one of our major banks? How about all four? David argues that while US banks were ‘too big to fail’, Australian banks are ‘too big to save’.

Toxic lending and excessive risk-taking has fed through to Australian property prices. Australians pay a premium on housing simply because our banks need to lift their profitability year after year and don’t bear the full risk of their decision-making.

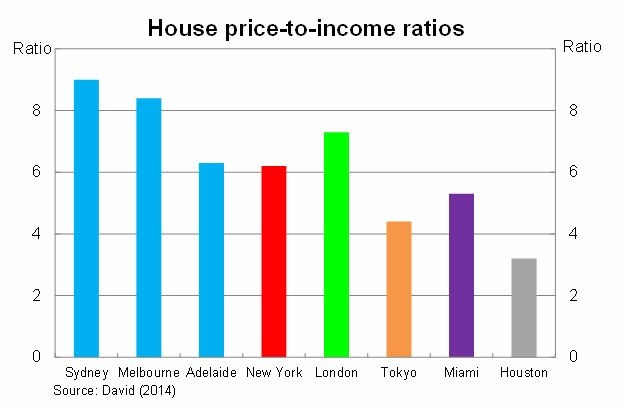

International comparisons highlight how expensive Australian housing is. The graph below contains housing multiples for eight cities, comparing Australia against some of the largest global cities in the world.

Based on population, Melbourne and Sydney are closest to Miami and Houston. But the house price-to-income ratio in Sydney is more than twice as high as it is in Tokyo, a city with over 35 million people. Remarkably, housing in Adelaide is more expensive than in Tokyo.

“The Reserve Bank and our politicians have either been asleep at the wheel or they have been managing a bubble. Not an economy,” David said.

David discounts the land supply hypothesis for high prices in Australia, and although I tend to agree that house prices are primarily driven by bank lending, our housing supply remains inflexible and slow to respond to changes in market conditions.

More responsible government policy would ensure that housing construction could react quickly to changes in demand, thereby reducing some pressure in the market.

But compared with China it seems almost comical to be concerned about Australian housing.

China has the most incredible housing bubble in the world -- perhaps in human history. First-home buyers in Sydney baulk at the house price-to-income ratios that they face; yet by comparison, some cities in China have housing multiples of between 15 and 40 times income.

Floor space per capita in China has surpassed 30 quarter metres, rocketing past the level in Japan during 1988 prior to their market collapsing. Housing construction continues at a rapid pace but annual population growth has slowed to just 0.5 per cent and China’s population will likely peak in the next 10 to 15 years.

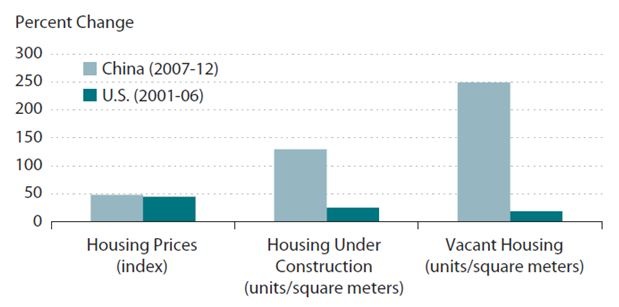

China’s housing bubble is perhaps best captured by a graph from the Federal Reserve of St Louis in a report last year. The graph is only to 2012 and since then the bubble has only expanded further, increasing the systemic risk to the Chinese financial system and by extension the Australian economy.

The Chinese property sector is already looking shaky, with property sales and prices taking a hit during 2014. With vacancies so high and speculation rife, a further deterioration is only a matter of time.

This will have important implications for the Australian economy and our mining sector, reducing commodity prices and slashing margins. Our major miners, BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, have some room to move but the smaller players remain vulnerable.

The Australian economy is poorly placed to deal with a shock from China and it is the most likely scenario that will result in a recession. The resulting unemployment and the sharp fall in the terms-of-trade will weigh on income growth and the housing market.

Australia’s housing market has suffered downturns -- three in fact over the past decade -- but it hasn’t been truly tested for more than 20 years. During the last recession, household debt was a mere fraction of its current level -- which means a household sector that is now more vulnerable to economic weakness.

A sharp correction to house prices, combined with the Chinese property bubble bursting, would put pressure on Australia’s banking sector. If one of them gets into trouble the other three will quickly follow suit and suddenly we’re off to the races with feedback loops costing jobs, further mortgage defaults and ballooning government debt.

David’s assessment of the Australian economy will not make comfortable reading but he has successfully outlined the major concerns facing the Australian economy over the next few years. No matter how you try to spin it, our banks are too leveraged, households are too indebted and our policymakers have become complacent. Unfortunately, as we head towards more challenging times, we find ourselves poorly positioned to handle an economic shock -- particularly if it comes from China.