The Reserve Bank's ugly growth challenge

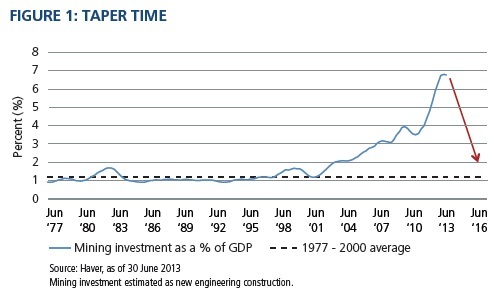

While the Federal Reserve gets to choose when to slow the pace of balance sheet expansion in the US, or when to 'taper', Australia does not have the luxury of controlling the balance sheet for the mining sector. Over the past 12 years, mining investment as a share of GDP has risen sixfold to nearly 7 per cent (Figure 1), but recent data suggest that this balance sheet is tapering, with the sector detracting from real growth in the first half of 2013. To encourage a new balance sheet to step forward, the Reserve Bank of Australia will have to keep interest rates low for an extended period, in our view, and likely lower them further to help smooth the transition away from mining-assisted growth over the cyclical horizon.

Which balance sheet, if any, will step up? We believe Australia faces three growth options over the next year, all with distinctly different policy and financial market outcomes – scenarios that could be called the good, the bad and the ugly.

Growth and taper of the mining sector

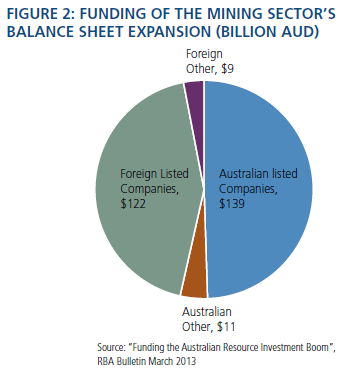

Between 2003 and 2012, the global mining sector is estimated to have invested $284 billion in new projects or expansions of existing capacity in Australia. Importantly, a significant portion of this investment has been funded by foreign entities. As Figure 2 shows, there has been close to a 50/50 split between domestic and foreign entities, with 46 per cent of this investment financed from offshore.

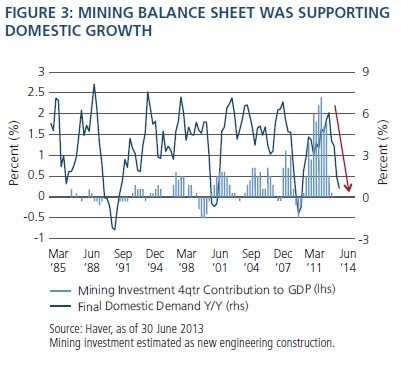

And as Figure 3 shows, since 2011 the balance sheet expansion by the global mining sector in Australia has supported domestic demand when much of the rest of the economy was growing below trend.

However, the first half of 2013 has been a different story, with growing evidence that this balance sheet has begun to taper its support. In the six months to June 2013, mining investment actually detracted 0.5 per cent from growth. With no new balance sheet stepping forward to drive growth, Australia grew by just 1.1 per cent in real terms in the first half of 2013. Excluding the first and second quarters of 2011, which were impacted by the floods in Queensland, this is the slowest six months of growth since the financial crisis ended in 2009.

The question now is what will happen as mining investment tapers and the Reserve Bank's interest rate cuts filter through to the economy. We see three possible scenarios.

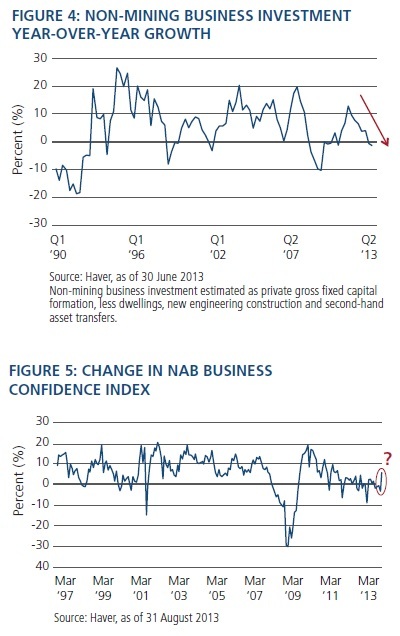

First, the good growth outcome the central bank is shooting for: Companies outside the mining sector begin to invest in their businesses again, allowing for a smooth hand-off of growth from the mining sector. Unfortunately, we have yet to see this process take place, with real growth in non-mining business investment actually contracting over the year to June 2013 (Figure 4). Could the recent uptick in business confidence after the federal election be a sign of stronger investment intentions going forward (Figure 5)? Perhaps, but we remain sceptical. Survey measures of hiring intentions and capacity utilisation remain at subdued levels, and we would need to see some sustained improvements in these measures before we would expect to see an increase in business investment. Additionally, the percentage of earnings that listed companies are paying out as dividends has continued to rise over the past 12 to 18 months, suggesting firms continue to prefer paying earnings back to owners rather than reinvesting in their own businesses.

Second, a bad growth outcome could eventuate in which demand continues to slow as the global mining sector tapers and no new domestic balance sheet steps forward to drive future growth. The first half of 2013 falls into this category, with the Reserve Bank responding by lowering the cash rate by 50 basis points so far this year.

And finally, an ugly growth outcome could transpire where an unintended balance sheet steps forward, attracted by low interest rates. In Australia, this would be the household sector, which remains highly levered by global comparisons. This ugly growth outcome would involve a temporary near-term boost to growth, but the increased leverage on household balance sheets from already elevated levels would create longer-term risks to the outlook.

The Reserve Bank would face a very difficult policy dilemma in this environment, constrained from providing the policy support required in other parts of the economy due to fears of creating imbalances in the household sector. This would prove a challenging policy environment not only over the cyclical horizon, but also over the secular horizon as growing imbalances in the household sector would also create growth risks and potentially ugly growth outcomes.

As we have expected in the New Normal deleveraging environment, there are no clear signs of this yet. In fact, real household consumption growth actually decelerated in June to its slowest year-on-year pace since the third quarter of 2009, and retail sales have grown just 1.9 per cent over the 12 months to July, well below the 30-year average of around 6 per cent. However, the potential for the household sector to expand its balance sheet is still real, particularly in light of the recent recovery in house prices. The Australian house price index rose 3.2 per cent in the first six months of 2013, its quickest pace since the first half of 2010.

Investment Implications

What does this complicated outlook mean for investors? Until we see some meaningful signs of a growth hand-off from the mining sector to a new balance sheet that has the capacity to expand, our base case calls for sub-trend growth outcomes in Australia. In this environment, we expect that the Reserve Bank will have to keep interest rates low for an extended period, and likely lower them further, supporting bond prices over the cyclical horizon.