The golden age of uncertainty

Summary: While markets don't like uncertainty, investors should. Rather than using low periods of uncertainty as a sign it's safe to venture back into the share market, use it as a contrarian indicator. Invest when times are uncertain for a more certain return and if you're funding a pension, try to avoid redeeming equities when uncertainty abounds. |

Key take out: Those who invest after markets suffer losses can gain the benefits of higher returns because the price at which they entered the market is lower, and they have the potential to benefit from any price rebounds. Keep in mind that by waiting for uncertainty to subside, you could be paying much higher prices for lower returns. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Shares. |

One of Warren Buffet's most memorable quotes is his contrarian suggestion to “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful”. While this is intuitively obvious, it takes a lot of courage to put in place. Having a quantitative framework to support decision making would be helpful. With the RBA publishing an index to measure economic uncertainty in February [ read more here: RBA) perhaps we have that now.

Measuring economic uncertainty with certainty

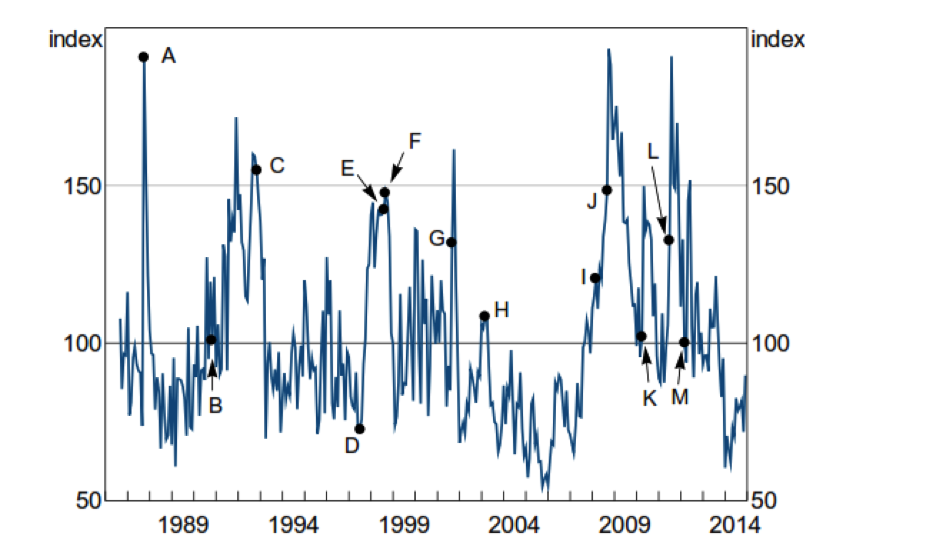

Figure 1 depicts changing levels of economic uncertainty in Australia since September 1986:

Figure 1: Economic uncertainty index and at key dates. Source: RBA February 2016

The index is constructed from four inputs: frequency of newspaper articles on “uncertainty” related topics, the volatility of share market options, dispersion between estimates of future corporate earnings and GDP growth forecasts. Press articles contributed 50 per cent to the index and the three other factors contribute one sixth each.

Index creator Angus Moore finds uncertainty “reduces investment and employment growth, raises the household savings ratio and reduces consumption growth for durable goods”. He concludes his study by suggesting: “Economic uncertainty can be an important independent driver of economic outcomes. It is therefore worth considering in policy and empirical work”. However he doesn't comment on its role in investment decision making…but we can, so let's consider the issue.

Returns from investing in certain and uncertain times

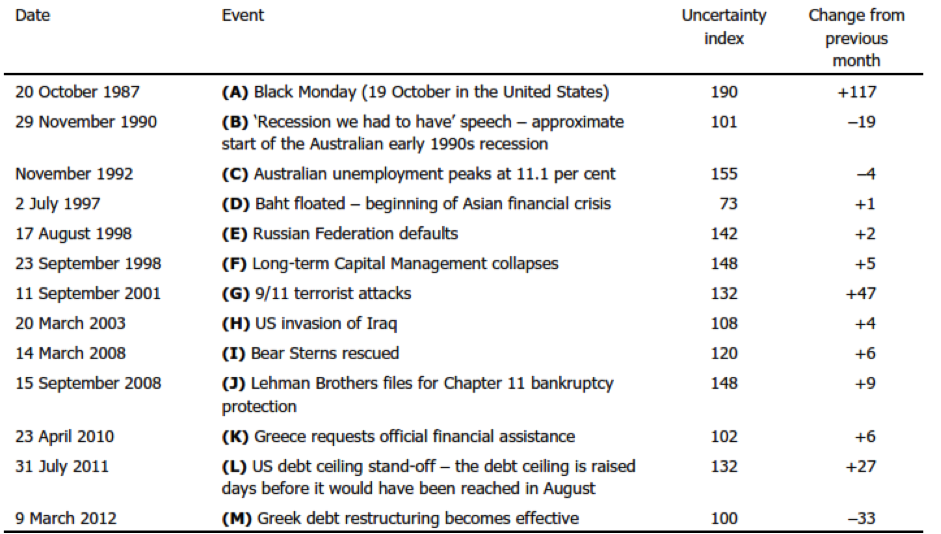

To see how investors fare investing during both certain and uncertain times, I have stacked on top of RBA's uncertainty index:

1) Local and overseas share prices,

2) Quarterly equity fund flows and

3) The one year later equity return.

I have also coloured in reassuring blue the five periods when the uncertainty index was below 100, and coloured in cautionary yellow the five periods when it went was above 100. Equity fund flows are for Australian domiciled, unlisted super and non-super equity funds, investing in local and offshore companies. They exclude purchases of direct shares and ETFs – the latter in recent years becoming more popular and taking capital from unlisted funds (and probably depressing the expected recovery in equity fund flows in recent years).

Figure 2: Economic uncertainty compared with Australian and World share prices, Australian equity fund flows (excluding ETFs) and the return investing at that time one year later.

Source: Professional Wealth analysis, RBA, Morningstar.

Investments markets and periods of high and low uncertainty are related in several ways:

The peak most profitable times for investment are when share markets are at a low, typically after a fall from a peak high (for example October 1987, November 2007). These generally occur during periods of peak uncertainty, however, rather than predict them, uncertainty is often a reaction to a share market collapse. While these are surprise events, you can still profit from them by investing immediately after they occur.

Since late 1986 the uncertainty index steadied below 100 for a combined 184 months, or 54 per cent of the time. During this period the average annual price return investing in Australian shares was only 2 per cent.

If instead one invested during the four periods, totalling 159 months, where the uncertainty index was over 100, they would have enjoyed a remarkable 9 per cent average annual price return.

In both cases investors faced an equal one-third probable future negative one -year price return. However, those who invested during more certain times were more vulnerable to a much larger negative return. Those who invested in an uncertain time were more insulated from future falls, having bought more cheaply, and often made a large profit from a share price recovery.

After periods of great uncertainty, investors who waited until uncertainty reduced to invest didn't always fare well. For instance those that ventured back into the share market in 2010 after share prices seemed to stabilise following GFC falls in 2008 and 2009 were belted by the 2011 and 2012 sovereign debt crises.

Investment flows

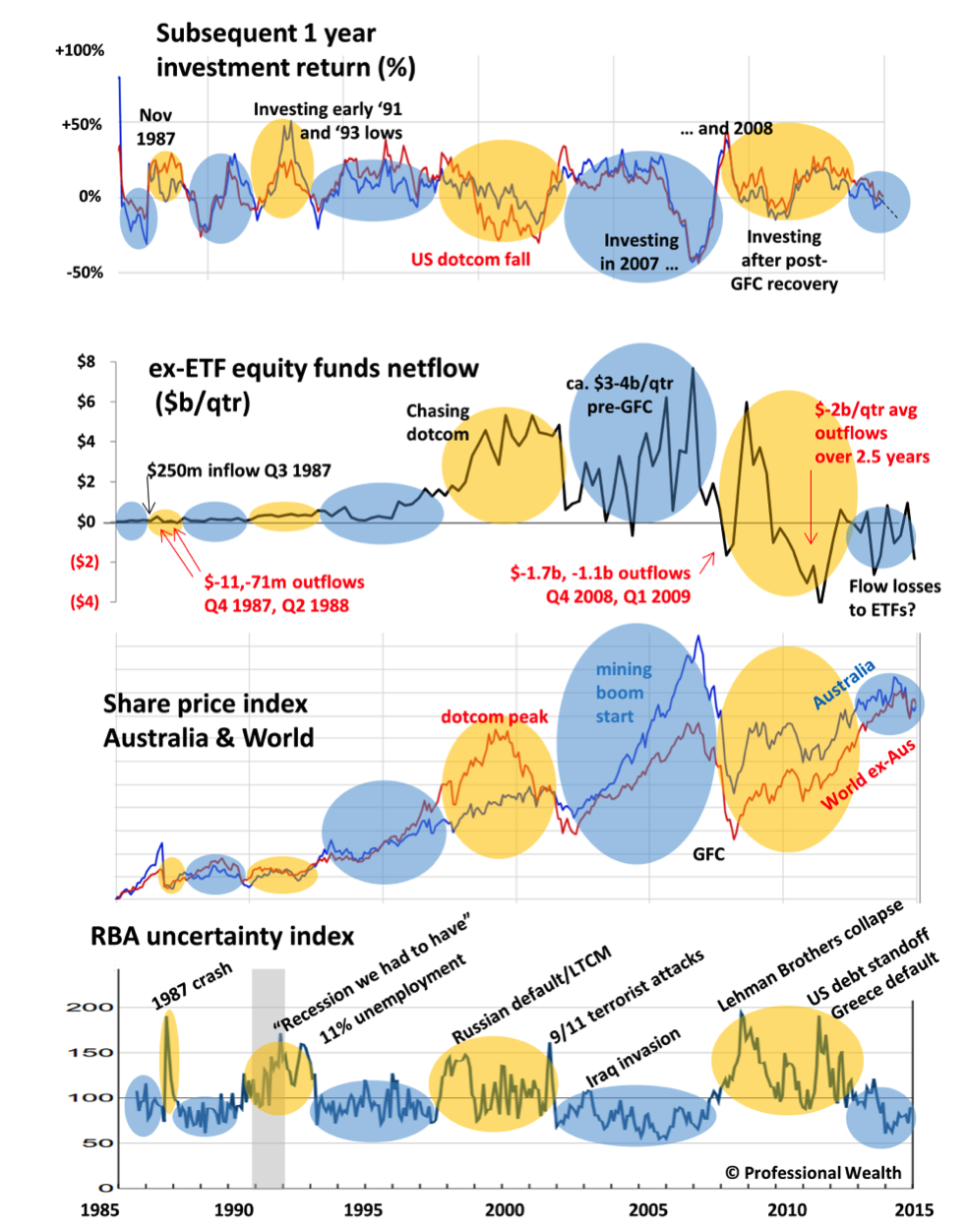

Thirty years is a long time to observe flows into equity funds given structural changes in the way investors access equities. However much can be understood from changes in fund flows around differing periods of certainty. I observe:

1) Large inflows often precede and accentuate a price peak,

2) Equity fund flows stall or reverse following a large share price fall, or during periods of great uncertainty and

3) They eventually recover after uncertainty falls and share prices recover – sometimes leading investors into an equity price trap.

This is not a local phenomenon. Figure 3 plots US investors' monthly equity fund flows over just the last 12 months where you can see this pattern continuing. About $20 billion per month flowed into US and International equity fund flows over the second quarter of 2015 while share prices were stable and conditions more certain.

However during August/September and January/February, when share prices fell, inflows stalled and outflows were larger than inflows. The only major inflows in the last six months were in October and December, the latter just preceding a second downturn in equity prices. Few felt brave enough to invest in September, January and February when share prices were at a local low. This looks like to me crap market timing!

Figure 3 Monthly US equity mutual fund flows for the 12 months to end February 2016 superimposed over equity share prices. Source: Professional Wealth, Morningstar.

US researcher Morningstar has studied both investment and investor returns for mutual funds. The former measures the return from an investment in the fund at the start of a period. The latter calculates an internal rate of return weighted to the amount of inflows into and assets in the fund. Their analysis (Read more here: Morningstar) shows on a weight of money average, investors earn about two per cent annual lower return by mistiming entering and exiting funds. Other US researchers Dalbar report a larger four per cent annual investor performance gap however the two decade time frame of their study makes it more prone to a methodological error arising from structurally lower recent returns.

In any case, we don't dispute that the average investor underperforms by piling more money into the market when times are more certain and share prices are higher. They don't help themselves further by withdrawing money in a downturn and waiting too long to return.

So what?

The RBA Uncertainty Index is a useful tool for economic policy making. However I'm not “certain” it should play a big role in your investment decision-making. As half the index is constructed from media reports, it probably isn't telling you too much you wouldn't be reading at the time. The causality of share price falls increasing uncertainty means you could just focus on share prices for a signal. However I do like how it puts a number on otherwise what is a feeling. Like fund flows it is probably a contrarian indicator, cautioning investors to invest during certain times and encouraging them to invest (more) in uncertain times – which is what a simple rebalancing discipline does.

As periods of low and high uncertainty can persist for years it is of questionable help being a market timing tool. Of course where possible it would be better to invest in times of uncertainty (applicable for accumulators) and divest during times of greater certainty (applicable for pensioners). Maybe investment guru John Templeton was right when he said “The best time to invest is when you have the money” … but I would add, just not as much when economic uncertainty is low.

Dr Douglas Turek is Principal Adviser with family wealth advisory and money management firm Professional Wealth.