The coming uplift in equities and property

| Summary: With policymakers determined to keep inflation under control, and to ensure that commodity prices don’t force their hand, and this could herald the dawn of a new golden age of uninterrupted asset price inflation. |

| Key take-out: While it’s not great news for those in the commodity space, it is for those in the equity and property markets, which look set to have another very long run in the absence of policy intervention (rate hikes). |

| Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economics and strategy. |

The Reserve Bank governor made an interesting point this week when he said that interest rates would likely be lower going forward than they have been previously.

I certainly think he’s right about that, but I’m not sure I agree with his view that this will be the result of some new found frugality among consumers. That view implies consumers no longer seek to maximise their well-being – that people won’t respond to record low interest rates. For me, you can’t turn over thousands of years of human behaviour and well accepted economic principles that easily!

Now I’ve outlined elsewhere why consumers will eventually take advantage of low interest rates. Confidence is shot – that is the only problem in Australia. But, over time, that will change, if not just through sheer boredom. (Robert Gottliebsen also points to some short-term global economic caution signals in his article today, Global caution signs you need to heed).

Asset prices will lift sharply. Don’t forget this is what we are already seeing in the US. Equities are at new records and housing prices are fast approaching, sometimes exceeding, records. It’s the same story in the UK, Canada, and even New Zealand where house prices in Auckland and Wellington are at record highs and still rising strongly – 20% annually in Auckland.

In Australia we’re in a completely different universe – still talking as if consumer deleveraging is weighing on the market and that asset price growth will be capped as a result. This is wishful thinking from policymakers, or perhaps a little bit of jawboning. Why would Australia be any different to what is going on right now in other Anglo economies, with our much lower unemployment rates and stronger fiscal position?

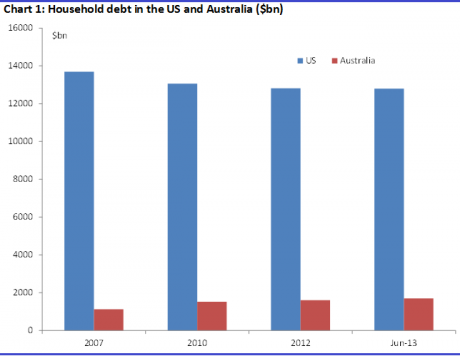

Often it is deleveraging which is cited. This is far from the reality. Take the US: The household debt to disposable incomes ratio has indeed fallen, to around 110% from a peak of 130%. Yet total consumer debt is really only off $US1 trillion since a peak in 2007 – from $US13.7 trillion to $US12.9 trillion now (see chart 1). That’s not a big fall, especially when you think that there have been nearly four million completed foreclosures. That means most of that decline in debt outstanding is due to debt destruction from loan defaults rather than from a conscious choice by the majority of consumers to deleverage. What we can say is that consumers haven’t opted to lift their debt. But, then again, amidst a housing crash there hasn’t been much reason to. That’s changing, and so is the appetite of US consumers for debt.

In Australia it isn’t even the case that that debt outstanding has declined. From 2007, household debt is up some $500 billion to a new record (about $1.7 trillion).

With that in mind, to expect record low interest rates to have such a modest effect - when the ability to service debt is the best it has been in over a decade (which is what domestic policy makers seem to be saying) – I think this is dangerously wrong. Moreover, it’s inconsistent with recent international experience. For high savings to be maintained and for assets prices and household indebtedness to remain unchanged, the RBA really would have to see a state of low confidence in perpetuity.

No, I don’t think any of that is the reason why rates will be lower for longer. It’s more subtle than that and has got more to do with something I wrote about last week: the steps regulators are taking cap gains in commodity markets (see my July 26 piece A red flag for commodity investors). It’s not that commodity prices won’t rise; they will for all the reasons I’ve outline in the past – pessimism on global growth has proved wrong. But if regulators follow through, we’re not going to see strong growth – record prices like we are in equities and housing.

Why is this so critical? Because inflation is unlikely to surge anywhere near where it would if regulators weren’t going down this path. This in turn could herald a golden age for equities and property.

Recall that the end game in all this regulatory scrutiny is to prevent the ramp-up in commodity prices that occurred in 2008. It wasn’t recognised at the time, but this is widely regarded now as being a key destabilising force during that period – a catalyst for the GFC.

Why? Because of the inflationary impetus it had. I mean, think about what brought the asset bubbles of 2007-08 to a close. It wasn’t the sudden realisation by policymakers that things had gotten out of control. They didn’t even know what was going on! It wasn’t excessive debt burdens, because at that time low rates made ‘high’ debt serviceable. No it was rising inflation, and the interest rate response to that. This is what closed the party down. At a very basic level, central bank rate hikes set off increases in adjustable rates for sub-prime mortgages in the US. This in turn set off the process of default etc., triggering, ultimately, the GFC. If rates were held low, there probably wouldn’t have been a problem – at the very least to the extent that we saw.

Here’s the thing: one of the key drivers of inflation over that period was higher commodity prices. While this fact was noted by policymakers around the globe, the extent to which commodity prices drove inflation outcomes was often understated. Instead, and readers may remember the press at the time, capacity constraints were regarded as the primary driver of inflationary pressure.

This isn’t what the data shows though. The surge in inflation up to 2008 had everything to do with surging commodity prices. Petrol prices rose about 30% in the three years to 2008; wheat and corn prices were up nearly 300%; copper up 100%. This flows through to rising airfares, rising feed costs, rising meat, bread, cakes, building costs. It hits utilities – gas and electricity prices – and it all increases the cost of building. Now it’s true that rents, education and medical expenses also surged over that period. But then they always do, and they are now. The swing factor was, and still is, commodity prices – food, fuel and the flow-through to other CPI items. I remember seeing at the time notices at bars telling me that beer prices were going up because of commodity inflation!

As I discussed last week, weight of money paid a big part in driving those commodity prices higher. There were fundamentals, very real ones, of course – and drought. But weight of money was a strong force (peak oil etc.). China was taking over the world and there were huge amounts of money flowing into (investing in) commodities. Regulators want to remove this source of demand by the looks. If they succeed, commodity prices will be lower than they otherwise would have – the speculative froth will be lower – and so too will global inflation.

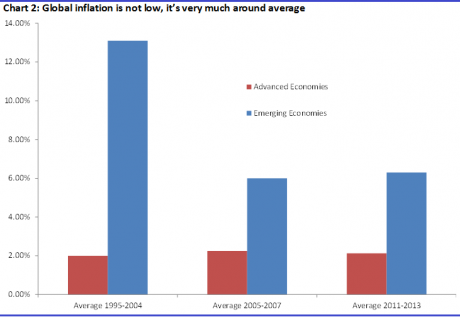

That doesn’t mean inflation won’t rise; it will and despite all the talk about low inflation it already has increased – back to average levels – which is perhaps why policymakers have ramped things up. Take at a look at the below chart.

It’s more that inflation will be lower than it otherwise would have been. No sudden commodity surge, no inflation surge like the one in 2008, and no rate hikes (well fewer). Inflation really spiked that year—it was highly unusual. This means, of course, that policymakers will be much more inclined to look through any lift in inflation we are seeing now because there will be less panic about it.

I wrote last week that the increased regulatory scrutiny of the commodity market could have profound effects and it will. Inflation is just one aspect of it. Lobbying efforts are strong though and I will admit surprise as to how successful regulators appear to be at the moment. The truth is I thought lobbyists would win the day, and it certainly looked that way when you saw all the loopholes and caveats in the Dodd-Frank bill (that was to prohibit banks trading on their own account).

While it’s not great news for those in the commodity space, it is for those in the equity and property markets, which look set to have another very long run in the absence of policy intervention (rate hikes).

Much will hinge on how firm policymakers are, but at the moment they look determined to make sure that a surge in commodity prices won’t force their hand.