Relaxing retirement drawdowns

There is no real need to make the case that retirees are facing challenges.

There has been widespread discussion of what record low interest rates, lower expected returns from growth assets and unfavourable Government decisions mean for retirees. That said, the recent deeming rate ‘debate’ and reaction by the Government to modestly change deeming rates to make them more favourable shows that changes can be made.

This article sets out to make the case for another change in regulation, which is a relaxation of the minimum drawdown rules for superannuation pension income streams, based on the current low investment earning environment. This change wouldn’t be unprecedented, as it’s similar to what happened during the Global Financial Crisis.

Lower expected returns

Let’s start by making the case for lower investment returns. Clearly, the cash rate is low. In theory, other investment returns, like the returns from investing in shares, are linked to this cash rate.

Shares, for example, provide an additional return for investors over the cash rate, referred to as a market risk premium. This is sometimes expressed mathematically as: Return from Shares = Risk Free Rate Market Risk Premium. Therefore, the lower the risk-free rate in the economy, the lower the total return from shares will be for investors. To put some numbers around this, let’s assume the market risk premium for investing in shares is 5 per cent per year. If the risk-free rate in the economy is higher, say 5 per cent a year, then the total theoretical return might be 10 per cent per year on average (always keeping in mind the volatility from investing in shares makes this a volatile return in any given year).

If the risk-free rate in the economy is low like right now, say 1.5 per cent a year, then the total theoretical return might be 6.5 per cent per year (1.5 per cent for the risk-free rate and 5 per cent for the market risk premium).

These calculations are only theoretical, but should provide a justification that a low cash rate is linked to lower expected returns in other asset classes.

Account-based pension drawdowns

In 2007, account-based pensions were introduced as a way of drawing an income stream from superannuation. These pension income streams were fairly simple, offering tax-free returns for the superannuation fund paying a pension while mandating a minimum withdrawal each year. Higher withdrawals could be taken if required.

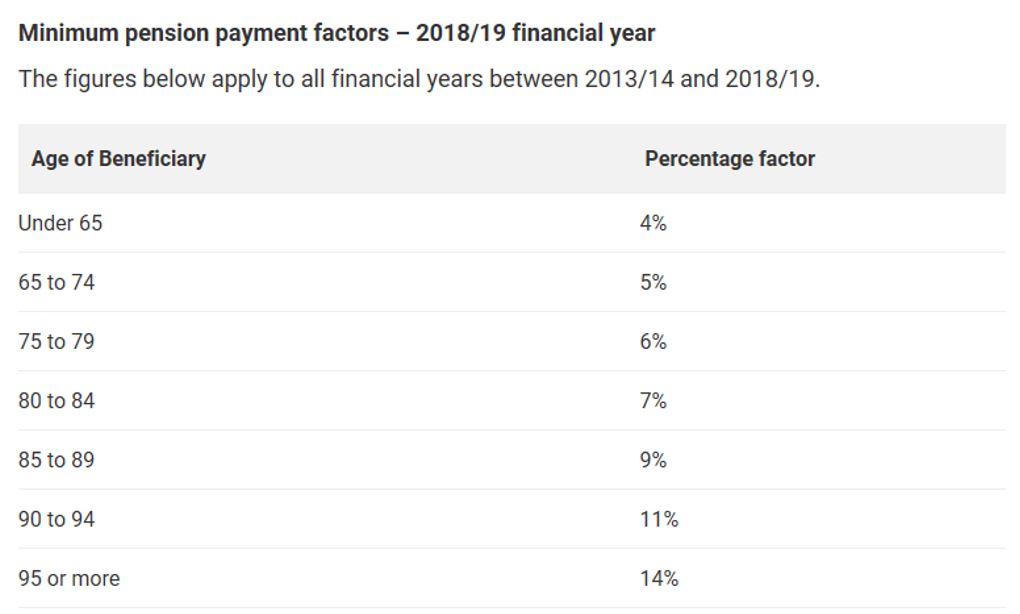

The minimum pension withdrawal starts at 4 per cent (for people up to the age of 65), rises to 5 per cent for people between 65 and 74, and increases all the way to 14 per cent for those people aged over 95.

Here is an interesting fact relating to account-based income streams when they were introduced in 2007. The RBA cash rate at the time was 6.75 per cent, meaning those people with an account-based pension under the age of 65 and drawing at a rate of 4 per cent per annum were not even drawing all their interest earnings on the cash portion of their portfolio. That’s a favourable position to be in. Today, the 4 per cent drawing rate forces people to be drawing at significantly above the cash rate of return.

Being forced to withdraw your capital

Even a portfolio made up of 50 per cent shares earning an average of 6.5 per cent a year (based on the theoretical calculation of returns), and 50 per cent cash earning 1.5 per cent, earns an average of 4 per cent a year. That’s assuming comparatively modest costs of 0.5 per cent per annum, 3.5 per cent after costs per year.

A person in the early stages of retirement with a 50 per cent growth/50 per cent cash portfolio is forced to be drawing a pension of 4 per cent a year, above the rate of portfolio income. That means, right from the word go, these investors are drawing some capital. In 2007, the same portfolio would have a theoretical return of 8.75 per cent, well above the initial 4 per cent withdrawal rate. On that basis, there is a case to consider whether these minimum withdrawal rates are still appropriate.

Reducing minimum account-based pension withdrawals

These aren’t normal times, even taking our lead from the conservative side of politics. Joe Hockey in 2013 described the 2.5 per cent RBA cash rate of the time as being ‘beyond emergency levels’. A cash rate of 1 per cent is unprecedented, clearly well beyond ‘beyond emergency levels’.

That suggests this is a reasonable environment to reconsider these minimum drawdowns – an approach that is not unprecedented, with the Government halving the drawdown rates for three years during the GFC, a decision that I’ve never heard linked to any negative consequences or costs. It was justified at the time as a way of giving people drawing a pension the option to draw less to not eat into their investment capital, a justification that equally fits today’s situation. Indeed, rather that negative consequences for the government, it would seem if a person was withdrawing money at a slower rate from their superannuation pension assets, they would be even less likely to require less government support in the future.

At a personal level, it is worth noting that if you are forced to withdraw more than you would like from your superannuation pension fund, you are not then forced to spend it. You can use it to build assets outside of superannuation, then use the income (and indeed capital) from those assets as you like. For many people in retirement who have little earned income, no tax is paid. That’s a solution very similar to having assets within the superannuation environment.

The only downside is complexity. The investor must then manage investments both inside and outside of superannuation. Sometimes the level of assets outside of superannuation will also create a tax liability.

Repeat, strange times

These are not normal economic times. A historically low interest rate of 1 per cent underlines this point.

With the swipe of a pen, the government could make a simple change to make things easier for retirees. It would mean referring to the GFC playbook to halve the minimum withdrawal rate for pension income streams. That would allow retirees greater flexibility to choose whether they want to withdraw their investment capital or not. As a low-cost option, it seems hard to argue against.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

Retirees are facing challenges due to record low interest rates, lower expected returns from growth assets, and some unfavorable government decisions. These factors make it difficult for retirees to generate sufficient income from their investments.

The case for relaxing minimum drawdown rules is based on the current low investment earning environment. Lower cash rates mean lower expected returns, making it harder for retirees to sustain their income without depleting their capital. Relaxing these rules would provide retirees with more flexibility.

Low interest rates lead to lower expected returns across various asset classes. For example, the return from shares is linked to the cash rate, and a lower risk-free rate results in a lower total return for investors.

Account-based pensions are income streams drawn from superannuation, offering tax-free returns while mandating a minimum annual withdrawal. The withdrawal rate starts at 4% for those under 65 and increases with age.

Current minimum withdrawal rates might be inappropriate because they force retirees to withdraw more than their portfolio earns, leading to capital depletion. This is especially concerning in a low-interest-rate environment.

During the Global Financial Crisis, the government halved the drawdown rates for three years to help retirees preserve their investment capital. This precedent suggests that similar measures could be justified today.

Reducing minimum pension withdrawals would allow retirees to preserve their investment capital, potentially reducing their future reliance on government support. It offers greater flexibility in managing retirement funds.

Yes, retirees can manage investments outside of superannuation. If forced to withdraw more than needed, they can reinvest the excess outside superannuation, although this may introduce complexity and potential tax liabilities.