Investor Psychology Series Chapter 5: Cultural Bias in investing

So far in this series I have focused on the individual and the individual habits and bias that can impact our investment decision making. However, humans are social creatures and there is a growing body of evidence that our society and culture is just as impactful on our decision making as our individual bias.

This is defined as ‘cultural finance’ and it’s designed to study both behavioural and cultural finance with a notion that ‘pure rationality’ is not a true event as culture does influence decision making.

This is interesting not just from a financial standpoint but also an economical one as economists traditionally assume biases are universal and tend to ignore how other factors might also shape our investment decision making.

What is culture in investing?

In the world of psychology, the father of defining culture is Dutch sociologist Geert Hofstede. He defined culture as ‘a collective mental programming of the mind which is manifested in values and norms, but also in rituals and symbols.’

This high-level sentence is basically saying that we interact, make decisions and form bias from an array of social and culture cues and norms.

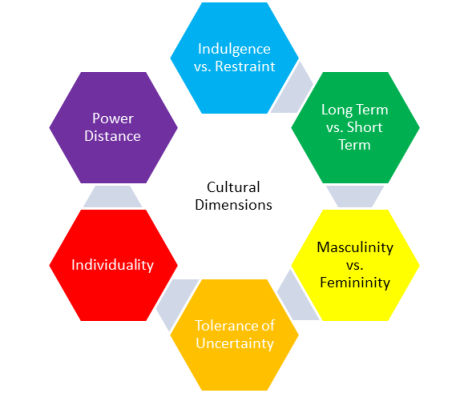

Hofstede breaks culture down into six dimensions seen here:

Be aware that the six dimensions are interlinked and cross over. So, for example, individuality, tolerance and masculinity are linked in their ideas. Same with femininity, collective and restraint.

Furthermore, the culture dimensions can be used to group societies. So, a collectivist society, such as East Asia, is where an individual’s identity is part of a larger social group compared to an individualistic society, such as Western Europe, Australia and the United State, is where personal values and achievements are more important features than the large social group.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions have had strong implications for behavioural finance, let’s examine this further.

A 2010 study by German behavioural finance and Game Theory experts Dr. Thorsten Hens, Dr. Mei Wang and Dr. Marc Oliver Rieger examined the risk and behavioural biases of nearly 7,000 investors in 53 countries. It found that the cultural dimensions of individualism, power distance and masculinity are significantly correlated with loss aversion.

This makes sense as individualistic cultures affiliate more with ideas of self-enhancement and independence. That is, people (investors) value and care more about an object (their investment) that is associated with themselves and a loss of the object (the investment) is seen as a reflection on them.

Contrast this with those from collectivistic cultures who tend to adopt holistic perspectives on a single object (their investment) and are therefore more able to cope with losses. The ‘collective society’ are also more likely to support the individual from a loss, which makes them less sensitive to losses.

The next dimension to look at is power distance which is measured as an index from 0 to 100 and is the measure of the distribution of power to wealth in a society. The higher the power distance, the more rigid the society is to hierarchy, discourages assertiveness, and encourages suppression of emotion.

To put this into the context of finance, if inequality is high (i.e., has a high-power distance), the average individual might feel more helpless about loss. Therefore, the higher the power distance, the higher level of loss aversion they might have.

Another part of Hofstede’s cultural dimension is uncertainty avoidance (UA), also known as tolerance of uncertainty. This is the measure of a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity.

A society with a higher UA score tends to be less tolerant of uncertain situations. In investing terms, those with a higher UA see the future as less predictable than the present and prefer immediate rewards (i.e., dividends or deposit yields) rather than future rewards (i.e., total returns). This is a big topic for behavioural finance as uncertainty avoidance is directly related to ‘time preferences’, as in, how long we can cope with uncertainty - think short-term market volatility versus long term investing.

What have we learnt from Part 1 of the Investor Psychology Series?

Behavioural biases are certainly important in navigating social situations and allowing us to quickly move between social interactions, however, they clearly impinge on our ability to make clear and concise investment decisions. But if we employ systems intended to counteract these instincts, such as feedback, audits of decision making and checklists, we can make more rational decisions and improve the chances of investment success.

What is also clear from this series is that you can benefit from understanding the driving forces behind investment decisions to make better ones into the future.

Other Chapters:

https://www.investsmart.com.au/investment-news/investor-psychology-series-chapter-1-overcoming-the-bias-of-human-psychology/148972?qa=true

https://www.investsmart.com.au/investment-news/investor-psychology-series-chapter-2-loss-aversion/149061

https://www.investsmart.com.au/investment-news/investor-psychology-series-chapter-3-heuristic-simplification-misuse-of-inform/149139

https://www.investsmart.com.au/investment-news/investor-psychology-series-chapter-4-the-human-psyche-and-diversification/149186

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

Cultural finance is the study of how societal and cultural factors influence investment decisions. It acknowledges that 'pure rationality' is not always possible, as cultural norms and values can shape our financial choices.

Culture influences investment decisions through social cues and norms that shape our biases. For example, individualistic cultures may focus more on personal achievements, affecting how investors perceive and react to gains and losses.

Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions include factors like individualism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance. These dimensions help explain how cultural differences impact investor behavior, such as risk tolerance and loss aversion.

In individualistic cultures, investors may prioritize personal achievements and self-enhancement, leading to a stronger emotional response to investment losses, as these are seen as personal failures.

Power distance measures the distribution of power within a society. In investing, a high power distance can lead to greater loss aversion, as individuals may feel more helpless in the face of financial inequality.

Uncertainty avoidance reflects a society's tolerance for ambiguity. Investors from cultures with high uncertainty avoidance may prefer immediate, predictable returns over long-term gains, impacting their investment strategies.

By understanding cultural biases, investors can make more informed decisions, counteract instinctual biases, and improve their chances of investment success through strategies like feedback and decision audits.

Investors can counteract cultural biases by employing systems such as feedback loops, decision-making audits, and checklists to ensure more rational and objective investment decisions.