Exploding shale

| Summary: Is Australia’s shale oil and gas sector set to ignite, or is such talk just hot air? While the US shale sector has boomed, there are key differences between what is happening there and the development of the Australian shale sector. |

| Key take-out: Flow rates to date have been disappointing, and considerable infrastructure investment will be required. It could be a while before the valuations of some companies operating in the sector are justified. |

| Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Commodities. |

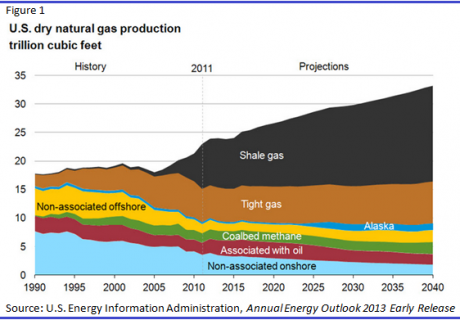

The US shale boom continues unabated. Rapidly growing oil production is dramatically reducing import requirements, while lower gas prices are driving a manufacturing renaissance.

With these successes, many countries are attempting to emulate the feat. A burgeoning shale industry is evolving in Australia, however it could be a long time before commercial production, and I caution investors in paying for the prospect.

Australia experienced its own energy boom only a few years ago. The dramatic consolidation of coal seam gas companies from 2007 to 2011 saw many investors profit handsomely from multi-billion dollar acquisitions of Sunshine Gas, Queensland Gas, Pure Energy and Arrow Energy.

These investors, and many who missed out, expect similar outcomes for the current crop of shale companies. While the recent entrance by BG and Chevron into the Cooper Basin is undeniably positive, I believe there are stark differences between the US and Australian shale assets.

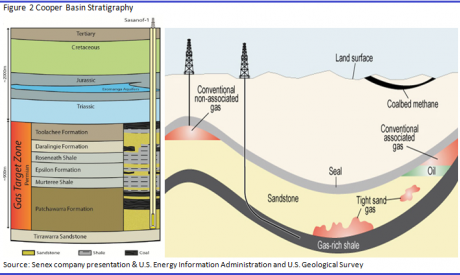

The Cooper Basin in north-east South Australia is by far the most advanced shale play in Australia. The basin has a long history of conventional production and therefore a rich dataset for initial analysis. However the geology varies widely through the play, challenging companies to identify prolific ‘sweet spots’.

Carbon dioxide, a significant negative in a shale project, ranges from below 10% to above 40%. Condensate loading, the amount of associated liquids within a well, is generally low across the basin. While these impediments may be overcome, the play is so embryonic it is still unclear as to whether best production would occur from the gas saturated coals, the tight sand or the shale itself.

Figure 2 highlights the stratigraphy of the Cooper Basin and the broad range of potential targets.

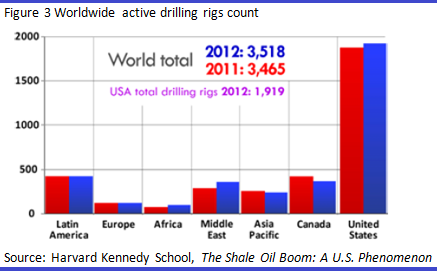

While the geological understanding of the play is evolving, another major challenge confronting the industry is that of costs. Capital efficiency is integral in shale production. Spud to spud times, frac costs and well costs are a few of the key success factors.

Costs have come down significantly in the US and Australian companies hope this will occur here too. However, as shown in Figure 3, costs have dropped significantly in the US because of the huge number of rigs and service companies operating. With only a handful of rigs in Australia, and our first horizontal well yet to be fracced, it will be some time before these benefits may occur.

In the US individuals and companies may possess property rights to mineral resources, while in Australia they belong to the Crown. This does not precude the profitable extraction of oil and gas from shale assets, but US landowners are freely capable of and often incentivised to transfer their property rights to the oil industry. Such a secondary market has facilitated rapid energy exploration and development, in contrast to what we have witnessed here in Australia.

A shale revolution in Australia would require the existence of an ample articulation of midstream and downstream infrastructure. Pipelines, storage, refineries, as well as adequate water supplies, would need to be established. The shale basins in Australia are in remote locations, and the cost of developing such infrastructure is prohibitive.

The commerciality of shale basins requires competitive capital and operating costs, high flow rates with shallow declines, and a clear access to market. Current horizontal wells in Australia cost roughly $20 million, three times comparative wells in the US.

Flow rates to date have been disappointing, and considerable infrastructure will be required. These fundamental challenges will prove difficult to overcome.

As a long/short equity manager, I look for sectors which have risen above fundamental value. Sectors where investors are paying for the blue sky and risks are not fully considered.

A number of shale companies in Australia are valued at over $500 million, and I believe it could be a long time before these valuations are justified.

Justin Braitling is a principal of Watermark Funds Management at www.wfunds.com.au.