A different spin on mortgage arrears

No matter which way you spin it, mortgage arrears in Australia are picking up, although arrears may not be the indicator that investors think.

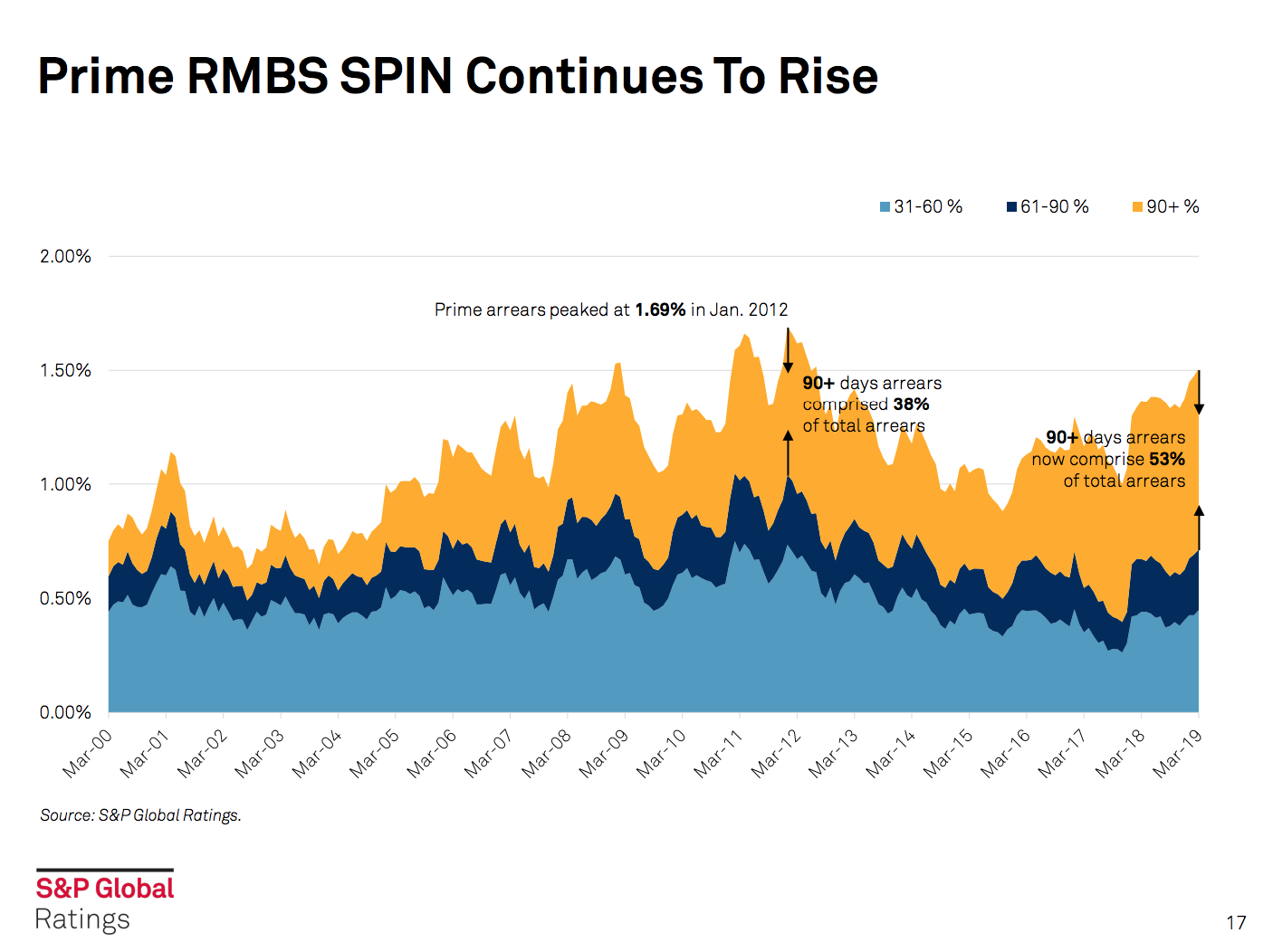

Standard & Poor’s (S&P) quarterly Mortgage Performance Index (SPIN) found more Australians are finding themselves in mortgage arrears for the first time. The 31-60 days overdue category increased the most over the first quarter of 2019, while the number of loans that are 90 days and more in arrears remained relatively stable.

Arrears events are said to be more common at the end of the calendar year because people overspend around Christmas and forget bills while on holidays. The long-run data may show that.

Money will buy you out of technical arrears, but your credit score will store the memory for at least 6-12 months.

As flagged by Erin Kitson, director of structured finance at S&P Global in Melbourne, the 90-plus day arrears bucket is much more problematic than that though.

“Once in a more advanced arrears category, that is serious, because the borrower has continued to struggle and self-manage their way out of arrears. It’s particularly concerning for these people at the moment, where lending conditions have been relatively tight.”

SPIN gains speed

In Australia, mortgage arrears were shown to take pre-GFC levels in the last SPIN Index. This wasn’t a blip on the radar, as the latest SPIN Index would show that mortgage arrears as a metric has only picked up a little more speed.

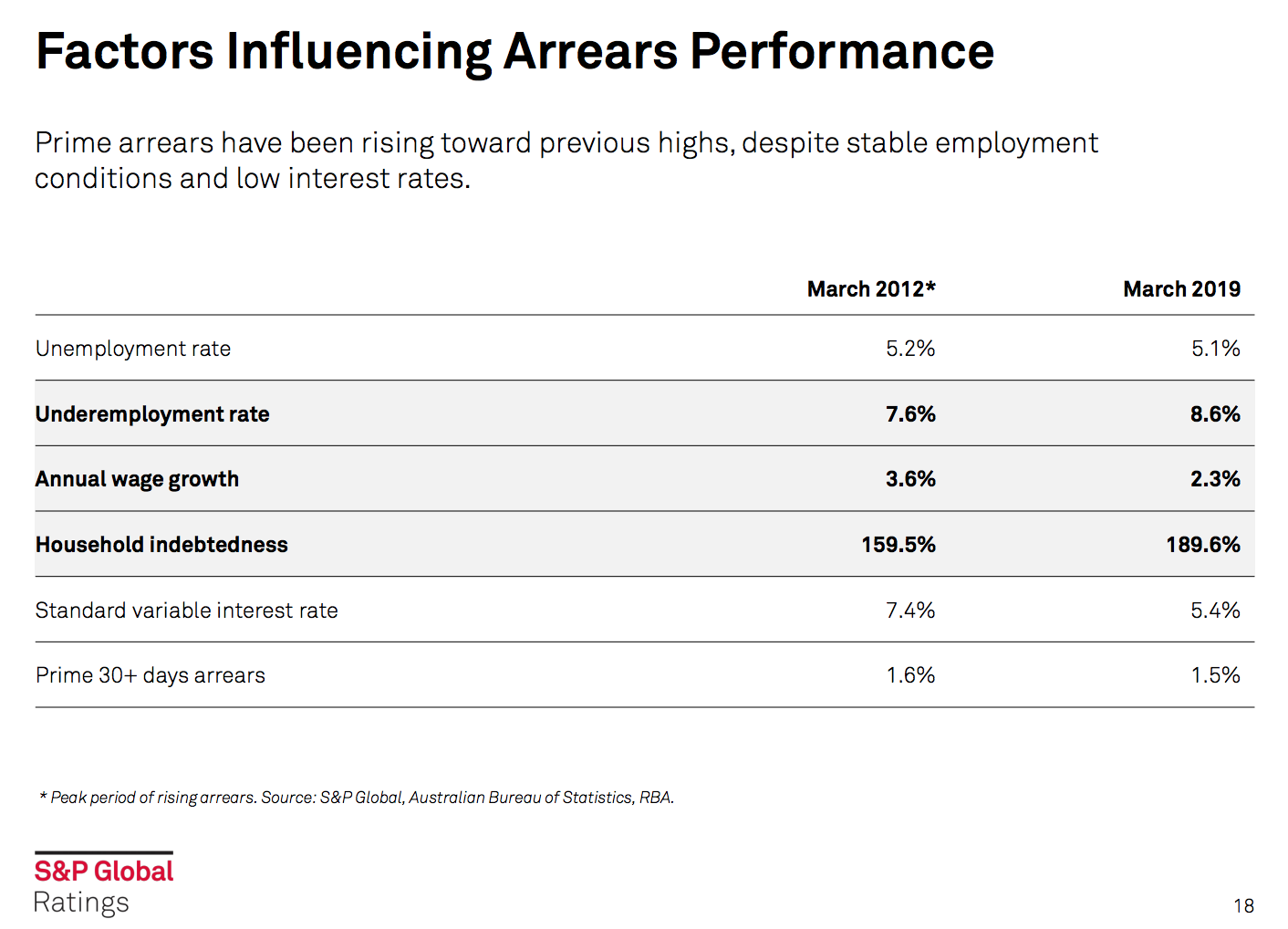

This recent uptick in mortgage arrears comes in the face of record low interest rates. The last steep increase occurred in tandem with rising interest rates in 2012.

However, this recent period marks a transition from interest-only to amortising loans, which affected serviceability in some cases.

As well, borrowers have a greater chance of entering arrears on higher loan-to-valuation ratios. Only around 2 per cent of loans captured by the data have LVRs greater than 90 per cent.

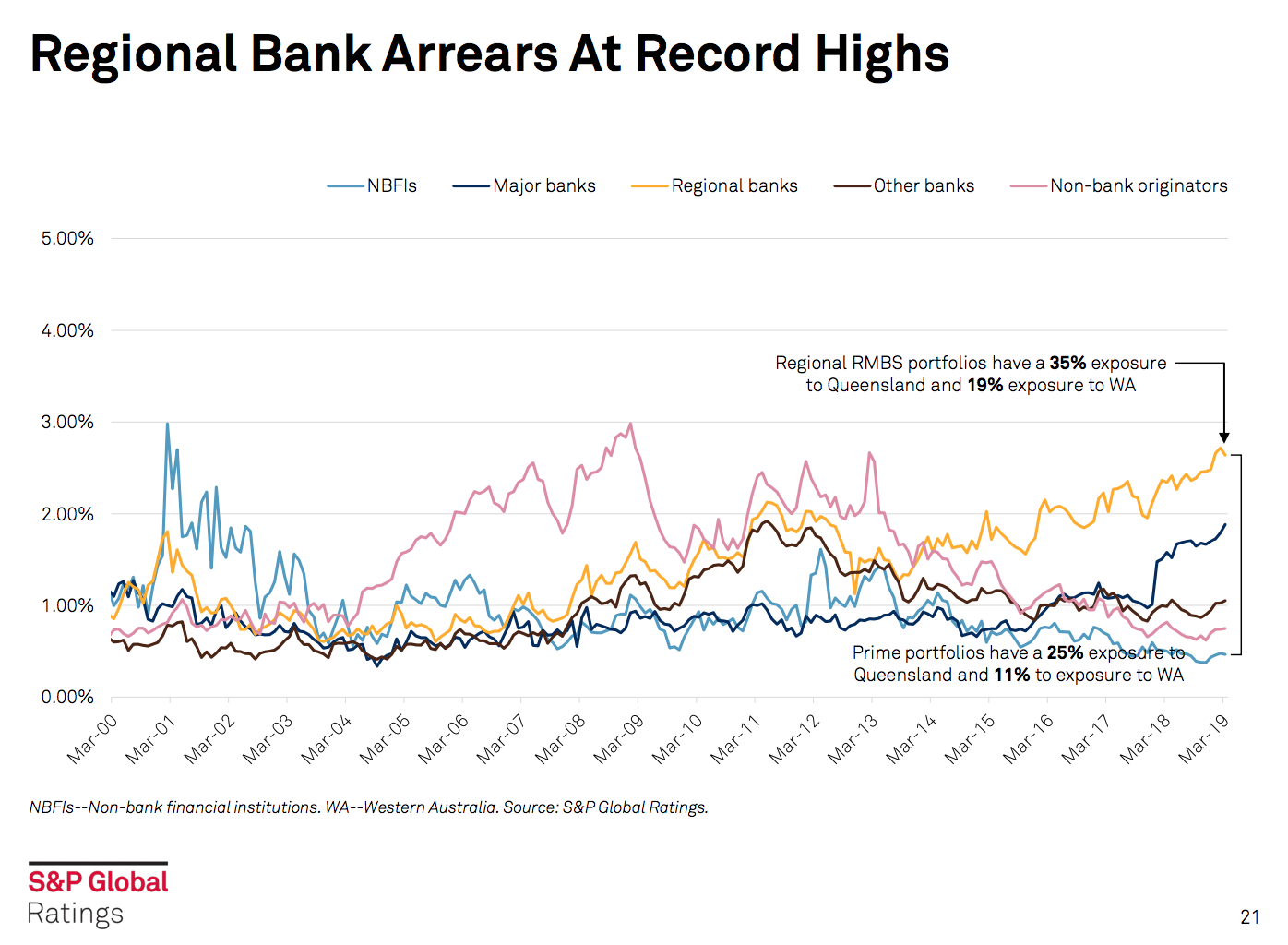

The Big Four don’t have the biggest problem with arrears. The regional banks stake that claim, being more exposed to QLD and WA, which account for more than 50 per cent of Australian mortgages in advanced arrears.

Meanwhile, non-bank lenders have comparatively been holding the line.

Kitson says much of this can be explained by seasoning. It takes a bit of time for a loan to go into arrears, and non-bank lenders have younger portfolios. But the steep, and since sustained, increase in mortgage arrears elsewhere may require a separate explanation.

A seasoned view on arrears

As Kitson will counter, there are new reporting arrangements in Australia, where the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) currently stipulates that lenders include loans under hardship arrangements in their arrears reporting.

“All lenders are now doing that, but historically that hasn’t been the case,” says Kitson.

“So where you see a pronounced uptick, some of that is a reflection of a revised uptick in arrears reporting to include loans under hardship arrangements.”

Regulators are still integrating lessons from the last crisis.

In the lead up to the GFC, the non-performing loan (NPL) rate for 90-plus day arrears was very low in Australia, Spain, Ireland, and both the US and UK. Dwelling prices were rising across the board, making it easier for distressed borrowers to sell at a profit, and refinancing was the status quo ante.

We’re no longer considered to be in a rising market, and it’s now a lot harder to refinance. Seemingly, investors are now less likely to be caught off guard.

And yet, a lagging indicator, of course, has a habit of sneaking up. Predating the GFC, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2006 referred to the NPL rate as a lagging, not a leading indicator:

“An increasing ratio may signal deterioration in the quality of the credit portfolio, although this is typically a backward-looking indicator in that NPLs are identified when problems emerge,” reads a key paragraph in the IMF Financial Soundness Indicators: Compilation Guide.

NPLs may appear once problems have already emerged, but the Australian mortgage market is built with another backstop to begin with. Kitson reminds that full recourse lending, versus limited recourse lending in the US, makes for a different kind of borrower behaviour.

“Australians hold on to that value of the home ownership,” she says. “They like to save their home and keep a roof over their heads at all costs.”

The most important thing

There are many technical ways to measure the health of the mortgage sector, with even more variance in effectiveness.

Kitson says one of the most basic metrics may be one of the best metrics, despite still being a lagging indicator.

“One of the key metrics, an economic indicator that’s really important from an arrears perspective, is the employment situation. If you are gainfully employed, you are obviously ok,” she says.

“The unemployment rate is still relatively low, and I think that’s holding pretty steady, and keeping arrears at this level. While employment conditions remain relatively stable, from the arrears perspective, I’m not expecting an increase beyond levels where they are now.”

Employment is something the Reserve Bank of Australia is keeping a keener eye on too, specifically the ‘gainful’ part of the employment equation. Underemployment is becoming less of a labour market pain, but persistently low wage growth continues to press on the market.

Ignoring the SPIN

Others forget the SPIN, and turn their focus to something a little more hedonic.

Late last year Coolabah Capital disputed how credit rating agencies measure mortgage arrears, claiming weighted-average data sets were “afflicted by severe compositional biases”. Briefly, that’s because new RMBS deals typically start out with performing loans only, which is what ultimately gets added to the SPIN Index. Coolabah Capital proposed a hedonic mortgage default index instead.

There are a lot of answers, but fewer solutions to improving the health of the mortgage market.

Above all, investors should learn the ropes of mortgage arrears and heed lessons from the past, but not take the data set as scripture. For now, it would seem, there are more important things to worry about, such as holding down a job.