Why the G20 should tackle rising protectionism

Free trade? What free trade?

A new report by Simon J. Evenett from the Centre for Economic Policy Research, highlights the dire state of global free trade. Protectionism is on the rise, with countries doing whatever it takes to find a small advantage over their global competitors.

International trade dropped sharply during the global financial crisis and has yet to completely recover. Despite the ascendency of China -- and strength throughout south-east Asia -- international trade flows are subdued and look to remain that way for at least a few more years.

In both 2012 and 2013, trade volumes grew more slowly than global real GDP. Trade has been pottering along at around a 3 per cent annualised pace over the past couple of years, compared with almost 7 per cent between 1985 and 2007 (Recent slowdown in global trade: Cyclical or structural, November 12).

Trade relations became more complicated in a post-crisis world, more desperate, and that has been reflected through the retreat towards protectionism and a return of the infamous currency wars.

The rationale was sound -- a softer currency supports export-exposed industries and encourages consumers to substitute from foreign-created to domestic products -- but globally it's also a zero-sum game. We can't all have a low currency!

As a result, it is hardly a surprise that countries have resorted to sneakier methods to support exports and their domestic economy.

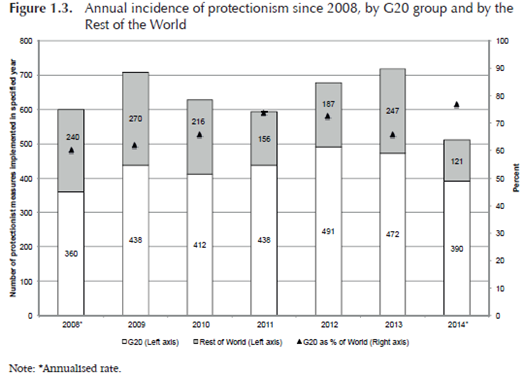

The number of protectionism acts has increased sharply since 2011 and last year topped the post-crisis high set in 2009. These are acts that are designed to support domestic enterprise at the expense of a foreign economy or commercial interest. They often involve actions that contravene established free-trade agreements.

It's important to note that there is a significant reporting lag so the results from 2013 and 2014, from the graph below, will be revised up significantly in future reports.

Protectionism has been overwhelmingly driven by G20 countries who have consistently accounted for between 60 and 70 per cent of new acts. That's broadly consistent with the global currency war, which has been concentrated among developed westernised countries.

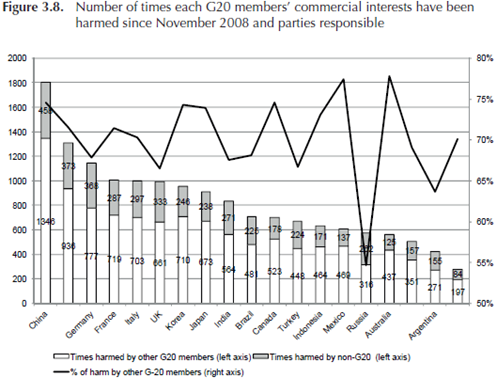

The EU has inflicted the most harm on foreign interests since November 2008 with 510 acts, followed by India on 354. Russia was in third place (338 acts), followed by Argentina (278) and the US rounds out the top five (206 acts).

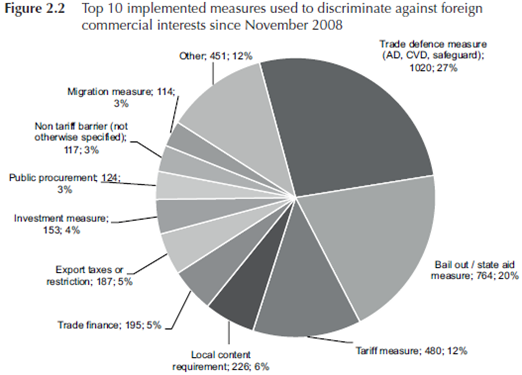

The top 10 measures are contained in the pie-graph below. Defence and bail out/state aid dominate.

How does Australia compare? We have imposed 78 harmful measures on foreign commercial interests since November 2008. It's a relatively small number -- Italy, for example, sits in 10th place on the chart with 134 harmful acts -- and reflects our stronger growth and outlook in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

To the extent that we have pursued protectionism it has been directed at China and the US, but given the volumes of iron ore and coal shipped abroad the numbers are probably too low to be of real consequence. It will however be interesting to see whether Australia becomes more protectionist now that our terms of trade has declined.

The same cannot be said of the rest of world. Almost half of all protectionist measures since November 2008 have been directed towards China. Australia has been hit on around 562 occasions -- well above the number of times we've intervened -- suggesting that we have been a loser from the retreat towards protectionism.

Naturally these figures beg the question: how do governments get away with it? According to Evenett, the answer might lie in the old expression “people who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones” (The Global Trade Disorder: New GTA data, November 13). Is protectionism now so widespread and pursued so readily that G20 members avoid criticising one another for fear they will be attacked themselves?

International trade is a messy affair. Multi-lateral agreements are almost impossible to create or maintain and bi-lateral agreements are often not as lucrative as first thought. These data from the Global Trade Agenda report indicate that free trade remains a fantasy in many countries, particularly where China is involved.

Trade is not universally beneficial -- there are clear winners and losers -- but on balance boosts economic activity in both countries party to the transaction. Given the nature of these measures, the winners have been those with the resources and connections to lobby hard for intervention. The losses have been spread across millions of households and businesses.

Free trade doesn't benefit everyone but a retreat towards protectionism benefits too few to be a viable approach to globalisation. The G20 might talk-the-talk during their discussions in Brisbane this week but are they ready to turn their back on protectionism in the pursuit of greater growth?