Why China faces four per cent growth: Pt. 2

This article is the second in a two-part series. The first half was published Friday 13 September, where Michael Pettis argued the upper limit of growth in China over the next ten years was four per cent because China would struggle to achieve a consumption rate of 70 per cent of GDP and investment could not be sustained at 49 per cent of GDP, an historical anomaly for emerging economies. He continues below.

So I assume that investment must drop as a share of GDP. One way or another, either because Beijing forces changes in the growth model, or because Beijing does nothing and allows debt to build to the point where debt capacity constraints are breached, after which investment collapses automatically and the investment share of GDP will drop substantially.

How long will it take? I am going to assume Beijing has ten years to bring investment levels down to the new “optimal” level just to make my calculations easier, but as in the case of taking ten years for consumption to adjust, I think this is an heroic and frankly implausible assumption. Debt levels are simply too high in China for it to continue this level of investment growth for so many more years.

To repeat the exercise, then, let me make two separate assumptions: that investment will drop to 40 per cent of GDP in ten years and that investment will drop to 35 per cent of GDP in ten years. In either case, I will assume that investment is currently 46 per cent of GDP, although it is probably closer to 49 per cent.

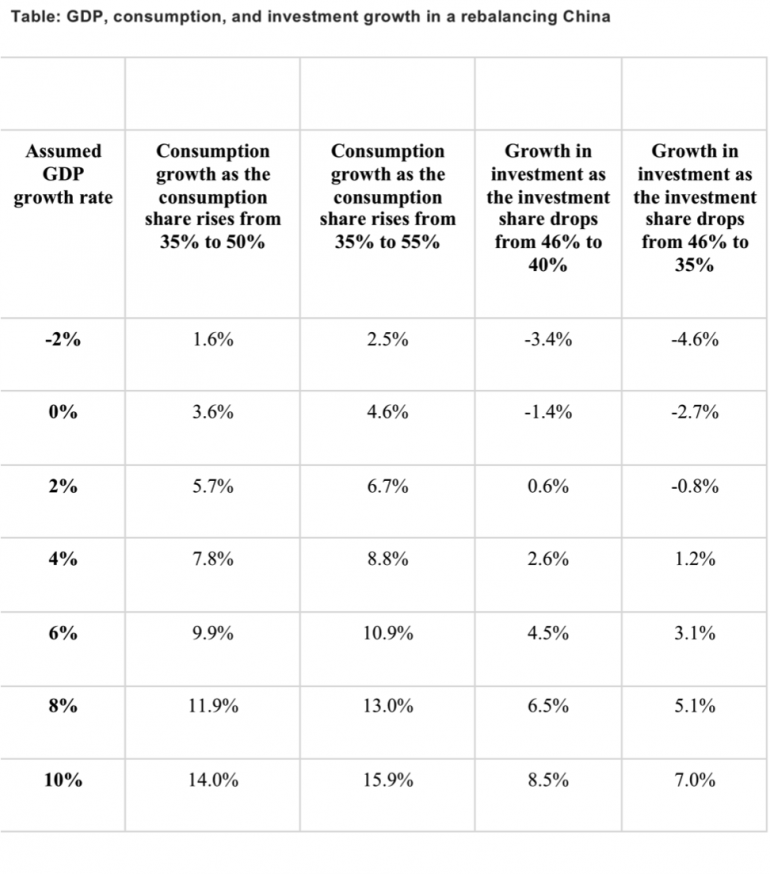

It turns out that it is fairly simple arithmetic to work out the implications of each of these assumptions relative to GDP growth. Rather than start with growth assumptions in consumption and investment and use these to determine what the corresponding GDP growth rate is likely to be, I thought it would be more useful if I reverse the process and simply assume a bunch of GDP growth rates ranging from -2 per cent to 10 per cent. These are the different average GDP growth rates possible under different scenarios for the next ten years.

We will assume two sets of adjustments for investment and consumption. The “easier” adjustment scenarios have household consumption growing from 35 per cent of GDP to 50 per cent of GDP, while investment declines from 46 per cent of GDP to 40 per cent of GDP. The “tougher” adjustment scenarios have household consumption growing from 35 per cent of GDP to 55 per cent of GDP, while investment declines from 46 per cent of GDP to 35 per cent of GDP.

The table below lists the consumption and investment growth rates needed for rebalancing to take place at each of the highlighted GDP growth rates.

To read the table, let us start by assuming, as an example, that we believe the average GDP growth rate over the ten-year period will be 6 per cent. For China to do a minimal amount of rebalancing that gets consumption to 50 per cent of GDP and investment to 40 per cent of GDP, we can quickly figure out what the corresponding growth rates of consumption and investment must be. Consumption must grow by 9.9 per cent a year and investment must grow by 4.5 per cent a year to get us there.

Notice the reason why I do it this way rather than the “normal” way most other economists would. Instead of estimating what I expect the growth rates in consumption and investment will be, and then calculating the implicit GDP growth rate from those numbers, I start with an assumed GDP growth rate and then calculate what the implicit growth rates in consumption and investment must be in order for rebalancing to take place. I am not making predictions, in other words. I am simply working out logically what any GDP growth rate must imply in terms of consumption and investment growth rates in order for China to rebalance.

This allows me to make statements like this: If you think that China’s GDP will grow by 7 per cent a year over the next decade, and if you expect a minimal amount of rebalancing, then you are implicitly predicting that consumption will grow by 10-11 per cent a year for ten years and that investment will grow by 4-5.5 per cent. If you believe these two implicit predictions are plausible, then your 7 per cent prediction is also plausible.

Trade is a residual

Notice that for the changes to work, we are implicitly assuming that the GDP share of the sum of other consumption (government and business) and the current account surplus changes automatically to allow the equation to work. For example, if consumption rises from 35 per cent of GDP to 50 per cent of GDP, while investment falls from 46 per cent of GDP to 40 per cent of GDP, the other sources of demand (mainly other consumption and the current account) must have reduced their share of GDP from 19 per cent to 10 per cent. This probably means a sharp contraction in the country’s current account surplus and perhaps even a current account deficit.

I want to state again that these numbers are not predictions. They are simply the arithmetically necessary growth rates that are consistent with our assumptions. To return to the interpretation of the table, let us assume again that China does the minimal amount of rebalancing so that in ten years, household consumption is 50 per cent of GDP and investment is 40 per cent of GDP. What are the investment and consumption growth rates consistent with, say, 6 per cent GDP growth, and are they plausible?

It turns out that average GDP growth rates of 6 per cent require, as an arithmetical necessity, that household consumption grow by 9.9 per cent a year over the next ten years and that investment grow by 4.5 per cent, after many years of high double-digit growth and more recently growth in the low-double digits. Is this plausible?

I would argue that positive investment growth rates for another ten years are highly likely to result in our reaching debt capacity constraints well before the end of the decade, so I am sceptical about the investment implications of this scenario. By the way, some analysts have mischievously pointed to the very poor construction quality in China to argue that investment growth rates have to stay high just in order to account for higher-than-estimated depreciation costs, and that this suggests that China can grow faster than what we might otherwise assume.

This, of course, is nonsense. The fact that buildings and infrastructure are poorly constructed means that China is worse off, not better off, and that investment projects will ultimately be required to generate sufficient returns to pay off even more debt than originally estimated. Because it is debt capacity constraints that constrain investment, anything that creates debt without creating additional productivity to service the debt cannot possibly be a solution. Higher-than-expected depreciation increases debt relative to debt-servicing capacity.

More importantly, I would argue that if annual investment growth drops to 4.5 per cent and GDP growth to 6 per cent, it will be very difficult — without significant and politically painful transfers from the state sector to the household sector — for consumption to grow at anywhere close to 9.9 per cent a year for ten years. Consumption growth is, after all, positively correlated with investment growth, especially in the internal provinces upon which a lot of useless investment has been lavished.

In order to get Chinese households to increase their consumption by nearly 10 per cent every year, I would argue that household income would have to grow at that rate, which means that wages, interest rates, and the value of the renminbi should in the aggregate increase rapidly to get consumption to rise fast enough. Of course, since it is precisely low-wage growth, low interest rates, and an undervalued currency that goose GDP growth, reversing them is not consistent with high GDP growth.

Can consumption grow at close to 10 per cent for ten years while household income grows much more slowly? Yes, of course it can, if the household savings rate declines. But as China’s economy slows and as concerns about debt rise, it seems to me a tad optimistic to assume that the household savings rate will decline sharply. Rising income and rising uncertainty both suggest that we should expect higher (not lower) household savings rates, which in turn imply that household income must grow faster (not slower) than household consumption.

All of this suggest to me that while 6 per cent GDP growth for the next ten years might not be impossible, it is extremely unlikely because it requires implausible assumptions about the ability to maintain and increase already-high levels of investment without increasing the debt burden unsustainably and about the rise in the growth rate of household income as both GDP and investment growth drop sharply. This is why even 6 per cent annual GDP growth rates, which are still lower than most current growth projections for China, are implausibly high.

What about if you believe that reducing investment is a much more urgent priority than raising consumption? In that case, you might argue that China can grow at 6 per cent while the household consumption share of GDP rises to 50 per cent and the investment share of GDP declines to 35 per cent.

In that case, you are implicitly assuming that household consumption will grow on average by 9.9 per cent a year for ten years while investment grows by 3.1 per cent a year. Is this possible? Of course it is. Is it plausible? Again, only if you believe that investment growth can drop sharply while the growth in household consumption rises to nearly 10 per cent a year for ten years.

So what is plausible? My working assumption, which I acknowledge is probably still optimistic, is that somehow Beijing can keep household consumption growing at around 7-8 per cent a year, even with a sharp decline in the investment growth rate and with the pressing need to clean up the banking system. (Remember that traditionally, in China and elsewhere, cleaning up the banking system always means finding ways of getting the household sector to pay for the losses.)

I know many consider assumption this to be a little optimistic. But if Beijing is worried about the social implications of adjustment, this is probably the target it will need to meet, and it can do so even with much slower GDP growth if the leadership implements mechanisms that transfer wealth from the state sector to the household sector. I discuss why this is the right growth rate for to target in more detail in a recent piece published on the Carnegie Endowment website and in an OpEd piece in the Financial Times.

The table above shows that if China is to do the minimal amount of rebalancing, which requires that the world accommodate large Chinese trade surpluses for another ten years, and that debt can continue to grow – quickly but at a lower rate than in the past – for another ten years without pushing China up against its debt capacity constraints, 7-8 per cent growth in household consumption is consistent with roughly 3-4 per cent growth in GDP. It is also consistent with more or less no growth in investment, which would bring the investment level down to 35 per cent of GDP after ten years.

These numbers are plausible, if still a little optimistic. This is something that I think Beijing can reasonably pull off – if it is able to manage political opposition from the domestic elite – because it can transfer resources from the state sector to the household sector at a pace necessary to keep the growth rate of household income and household consumption fairly high. However GDP growth rates significantly above 3-4 per cent, I would argue, require assumptions that are unlikely to be met unless Beijing is able radically to transform its attitude to state ownership and the power of the elite, and so embark on a major transfer of assets from the state to the household sector.

This is why I have argued since 2009 that 3-4 per cent average GDP growth for a decade is likely to be the upper limit once Beijing seriously begins to rebalance the Chinese economy. If the administration of President Xi and Premier Li is able to pull this off, it would be a huge accomplishment.

China would rebalance substantially, the problem of debt would have been managed relatively well, and the income of average Chinese households will have nearly doubled over the decade. The key assumption, of course, is that in the face of a sharp drop in investment, Beijing is nonetheless able to maintain current high levels of consumption growth.

Before closing it is worth pointing out that many analysts have told me that they do not think it is possible for household income growth to exceed GDP growth for many years. But why not? After all, state income growth exceeded household income growth for many years, and if Beijing reverses the mechanism that accomplished this – albeit with political difficulty – it can reverse the relative growth rates.

Japan did just this after 1990, when GDP grew by around 0.5 per cent annually but household income and household consumption grew by between 1 per cent and 2 per cent. The US did this too in the early 1930s when, if I remember correctly, household income and household consumption dropped by a lot less than GDP (around 35 per cent) and investment (around 90 per cent).

But notice these two examples. One occurred under conditions of no growth and the other under conditions of negative growth. Severely unbalanced systems always rebalance in the end, but the process of rebalancing is rarely easy.

Michael Pettis is a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a finance professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management. He blogs at China Financial Markets.