Why Australia is floored by sky-high house prices

Was the International Monetary Fund right to question Australia’s housing market? Or does it simply not get that Australian property is ‘different’?

Unfortunately, it has a point. Our major banks, the government and the Reserve Bank of Australia have a lot to answer for.

Australians take great pride in their property, which is understandable since we pay a bloody lot for it. Whenever our property market is questioned -- often by a foreigner -- our reaction is usually defensive.

Don’t they realise that we are ‘different’? Don’t they realise that we’re not subject to those pesky economic rules that bind everyone else?

Unfortunately, the reality is that we’re not different. Sure, our cities have some unique characteristics -- coastal locations and great weather being just two -- but our differences don’t explain why we pay so much more for housing.

I find that many Australians don’t truly appreciate how expensive housing is in Australia. Two simple examples might shed some light on the subject.

Sydney dwelling prices, for example, are around 50 per cent higher than prices in New York, despite New York being home to more accumulated wealth than anywhere in the world.

A more amusing example, sourced from Lindsay David’s Australia: Boom to Bust and independently verified, is that the median price in Mildura -- a country town with a population of around 30,000 people on the Victoria / New South Wales border -- is broadly similar to house prices in Chicago -- the third biggest city in the United States.

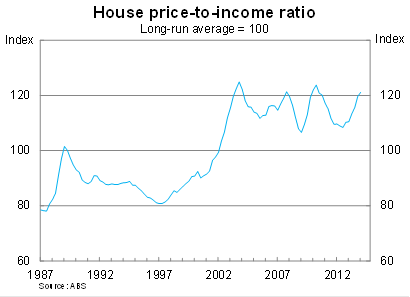

The IMF was right to highlight that housing has become increasingly costly over the past few decades. As the graph below shows, housing as a share of income is approaching its highest level in history.

What most Australians don’t realise is that it doesn’t have to be this way. The current predicament -- high prices and elevated indebtedness -- is completely intentional. The fault lies with our major banks, the RBA and government policies.

Housing cannot climb to such great heights unless the banks allow it. The rapid rise in house prices over the past thirty years partly reflects banking deregulation but also loose lending standards from the major banks.

We shake our heads at the US over their lending practices leading up to the global financial crisis, but banks in Australia routinely lend two or three times as much to couples who need support from their parents simply to make the deposit.

Banks have gone all in on mortgages and face massive losses in the case of a prolonged housing slump. But a short-sighted approach, which emphasises near-term profitability as opposed to sound investment, encourages the major banks to continue pushing billions into our property sector.

As if poor lending standards weren’t enough, the government weighs in with a variety of policies that promote speculation at the expense of home ownership. Negative gearing and capital gains concessions make housing an increasingly attractive investment. While the first home buyer grant creates the illusion of affordability for young Australians when in reality it simply redistributes funds towards the wealthy.

State governments help to keep prices high by limiting the land released for development. High house prices lead to more stamp duty and that is a major source of state revenue.

The RBA’s main fault is one of inactivity. They lowered rates in order to stimulate the non-mining sector but so far credit growth has been concentrated in housing. The RBA has a range of tools available to slow the housing market and encourage banks to redirect their credit towards the business sector but have instead decided to do nothing (A housing policy lesson from New Zealand, February 19).

Many Australians, to their credit, have taken a fairly cautious approach to their mortgage repayments. The aggregate mortgage buffer -- a measure of balances in mortgage offset and redraw facilities -- sits at almost 15 per cent of outstanding loan balances or around 24 months of total scheduled repayments at current interest rates.

However, it is also important to recognise that these balances are likely to be held by households who have been paying down their mortgages for a lengthy period of time. There is limited offset and redraw facilities for households that have taken on considerable debt recently; that group remains vulnerable to loss of income.

Australians need to change the way they view property; we shouldn’t be proud of paying $1 million for a dump in Sydney. Nor should we have to.

The only thing ‘different’ about Australian housing is the loose lending standards and poor policy that underwrite it. Australian banks encourage increasing indebtedness as a way to boost near-term profitability but the only people who benefit are the banks, the real estate agents and those who purchased properties more than a decade ago.

If we were wise, we wouldn’t discount the comments from foreign commentators. Instead, we’d take their advice on board and lobby our state and federal governments and the RBA to finally do something about housing affordability.