When bricks and mortar crumble

The price of your home could well be 49 per cent overvalued.

That's the conclusion of a global survey by Deutsche Bank that ranks Australia as the fourth most overvalued housing market in the OECD after Canada, New Zealand and Belgium.

Deutsche Bank's chief economist Peter Hooper arrives at these figures by comparing where home prices are relative to incomes (38 per cent above the historical average) and rents (60 per cent above historical average), then averages the two measures.

It's not that far off calculations by the Bank of International Settlements last year that placed Australia as the second-most expensive housing market globally out of advanced economies and said there could be reasons to expect a price “correction”.

The rankings will send a shiver down the spine of homeowners, whether they have ridden the house price boom of the past 20 years and probably bought investment properties as well, or more recently scraped in to an entry-level, newly built flat for $350,000 that is little more than a glorified studio.

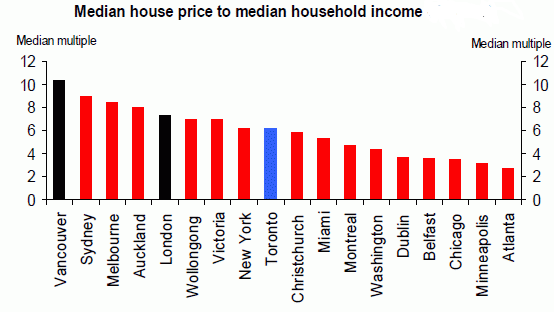

But this is the chart that should really terrify owners and policymakers alike. It shows that housing in no less than three Australian cities -- Sydney, Melbourne, Wollongong -- is more expensive than New York.

Source: Deutsche Bank

The cost of living in Australia is surprisingly high, and this is reflected not just in elevated house prices but in the high cost of goods and services. The cost of food in both supermarkets and restaurants is a constant source of astonishment to visitors from the UK and the US.

Whereas many countries experienced a bursting housing price bubble in the wake of the global financial crisis (led by the 40 per cent collapse in Ireland) Australia, Canada and other massively overvalued offenders have not. Nominal house prices rose 45 per cent from 2007 to the third quarter of last year.

Figures on Tuesday showed that 47.5 per cent of homes bought before January 2008 were sold for more than double their purchase price, compared with only 4.1 per cent bought after that date.

The Reserve Bank held official interest rates at historic lows for 16 months, and markets are toying with the possibility of further cuts. That helped lift the median house price in Melbourne 7.6 per cent last year to $587,000 and in frothy Sydney by 12.4 per cent to $730,500, according to Core Logic.

Central banks have been so preoccupied with consumer price inflation and preventing a damaging slide into deflation which causes businesses and households alike to stall activity that they have deferred rapidly inflating asset prices into a problem for another day. But the consequences of a housing market collapse in Australia are just as serious and would have ramifications across the economy and financial system.

Unable to raise rates, authorities have announced initiatives to monitor bank lending practices, focusing on interest-only loans and loans with high loan-to-valuation ratios. The controls, from the financial system regulator APRA and corporate watchdog ASIC, could lead to higher capital requirements if the regulators find signs of weakening lending standards.

The shifts in mortgage lending have been dramatic in recent years, reflecting the growth in speculative investment. Owner-occupiers now account for less than half of all new mortgage lending, ABS figures show.

In November, new lending for property investment sneaked up to a record 50.5 per cent of all new mortgages written, with property a favourite investment of many of the country's 1.2 million self-managed super funds.

For interest-only loans -- the ultimate bet that the value of the asset will not fall below the amount of capital borrowed -- the big concern is that borrowers are over-extending themselves. These risky loans have risen to a record high 42.5 per cent of all property loans, according to ASIC.

For such loans to work, house prices and wages need to keep rising while interest rates don't. Yet we are seeing an increasing trend towards stagnant wage growth, and interest rates rise as well as fall.

This raises the question of which banks are most exposed to a downturn in the housing market, particularly in the investment segment.

Westpac and NAB appear to have increased their investment lending at the fastest pace of the big four over the past year, up 10.5 per cent and 11.6 per cent respectively. Both are above the 10 per cent growth rate that APRA has raised as a red flag and may be among the first to receive a solicitous visit from regulators in the new year.