Waiting for the wealth shock to wear off

In my household at present, a certain eight-year-old is often found dancing around and singing: “The hip bone's connected to the back bone/ The back bone's connected to the neck bone/ The neck bone's connected to the head bone...”

Meanwhile, Dad is more often found humming: “The jobs rate’s related to consumption, consumption’s related to sent-i-ment, sent-i-ment’s connected to real in-comes...”

Around the nation business leaders, economists, politicians and journalists are singing a broadly similar song, wondering which part of the economy will rattle first and provide a much needed boost to growth.

While the last reporting season produced results mostly in line with expectations, many firms are delaying investment and job creation while waiting for consumers to get their collective mojo back.

But at the household level, real wages are falling, consumers are nervous about job security, and on the asset side there is growing talk of corrections in the red-hot housing market and range-trading equities market.

JP Morgan economist Stephen Walters calls it “post-traumatic (financial) stress disorder”.

In a note to clients last week, Walters explained why Australia -- the nation that sailed through the GFC better than virtually another other -- could nonetheless be in a kind of shock.

The chart below, from Walter’s note, helps explain this shock. Although wages kept rising through the first couple of years after Lehman Brothers collapsed in October 2008, the end of the terms of trade boom in late 2011 set households on a different course.

As Ross Garnaut predicted in his book Dog Days, once that high point had passed the strong likelihood was that wages would grow more slowly than inflation -- that is, the ‘real’ purchasing power of household incomes would be in decline.

Walters notes “sluggish wage growth at just 2.5 per cent on one year ago, the weakest advance in the history of the wage price series dating back to 1997”.

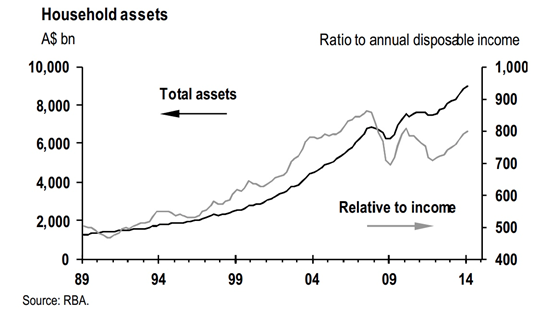

But the real cause of the ‘trauma’ was the hit to asset markets. Going into the GFC Australians collectively held $7 trillion in assets and national disposable income for the year of about $0.7 trillion. (Disposable income is simply gross income minus taxes -- the part that can be spent or saved).

We now hold more like $9 trillion in assets, but don’t feel as confident about their future -- or see them as being as valuable in relation to wages and prices.

As the chart above shows, assets recovered from the Lehman Brothers slump, but wages kept rising until the 2011 inflection point -- meaning the asset-to-disposable-income ratio fell back until the end of that year and then started tracking asset values again to the present day.

That’s a slightly confusing way of saying that since the end of the 1991 recession, household assets grew ahead of wages, and the breaking of that trend has left us all a bit shell-shocked.

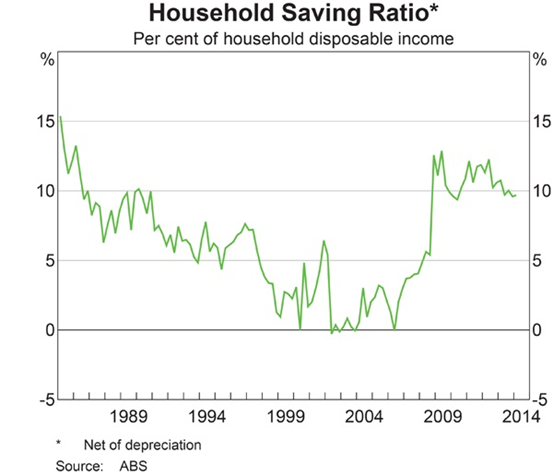

That shock is reflected most clearly in the savings rate, which remains historically high -- around 10 per cent of our disposable incomes are saved, whereas just before the GFC we were spending so much more than we earned, via bank debt, that the savings rate was occasionally negative (see chart below).

That’s no mean feat, when you consider that the savings rate includes our forced superannuation contributions. To hit zero, we effectively have to spend as much in money we don’t have (i.e. take on more debt) as we save for retirement.

And that is what happened in the debt-fuelled consumption spree between 2000 and 2007.

Now, as the nation scrimps and saves, retailers and a host of other businesses watch their bottom lines nervously, and hold off on the investment, jobs creation and general ebullience that comes with economic growth.

The latest worrying sign is the slide in new car sales.

As the RBA recently reported, the elevated incomes of the mining boom years “mean that motor vehicle purchases may have been 30 per cent higher as a result of the mining boom, and [consumer] durables 25 per cent higher”.

With the combination of falling terms of trade, sluggish wages growth, and the end of the wealth effect that flowed from buoyant asset markets, consumers really are suffering ‘financial traumatic stress disorder’.

At JP Morgan, Walters thinks they may snap out of it by mid 2015. Let’s hope so.

Then again, the Abbott government’s first budget didn’t help -- if there is a rebound in confidence, and fall in the savings rate, it might take the Abbott government uncomfortably close to the next election before the bones of the Australian economy rattle back to life.