To Labor GST means 'good scare tactic'

One of the ironies about the simmering debate over raising the GST is that Labor, the party digging in against an increase, is more naturally on the side of politics that should be championing such a move.

As Saul Eslake puts it, value-added taxes have been most heavily used by Labor's “fraternal socialist colleagues in Europe”.

That may seem counter-intuitive. When a single mother, working part-time, buys new shoes for her child, or when an unemployed young man wants to invest in a bicycle to allow him to get to a greater range of employers, why would you want to sting them 10, 15 or 17.5 per cent tax at the point of consumption?

The answer lies in the big picture, not those micro-level emotive images.

Let's stick with a young man, Frank, looking for work -- an increasingly common scenario in Australia, as youth unemployment continues to rise.

Frank wants a $200 bike at Kmart, but because of the 10 per cent GST, he has to fork out $220. If the GST rises, it might even be $230.

But he also wants to ride it to a factory or office where there is some kind of job available -- and the difficult truth for the left of politics is that the structure of our tax system has a lot to do with whether jobs are being created.

At present, federal government revenues have become too dependent on taxing company profits at 30 cents in the dollar, and on income taxes at marginal rates of 19 cents, 32.5 cents, 37 cents and 45 cents depending on how much an individual earns.

Capital gains tax has been important too, but let's leave that out for now for the sake of simplicity and because asset markets are showing uneven growth at present anyway.

The standard lefty cry when tax reform is discussed is “raise the top marginal tax rate, raise the company tax rate, and DON'T YOU DARE RAISE THE GST”.

And when Frank hears this just before cycling to the voting booth on election day, he'll know the left is taking care of people like him -- tax the rich, tax those big corporations and keep the price of things down by leaving the GST untouched.

But Frank still has no job. And worse still, neither side of politics is able to pay for decent unemployment benefits and health care. Somehow he's not feeling that looked after, after all.

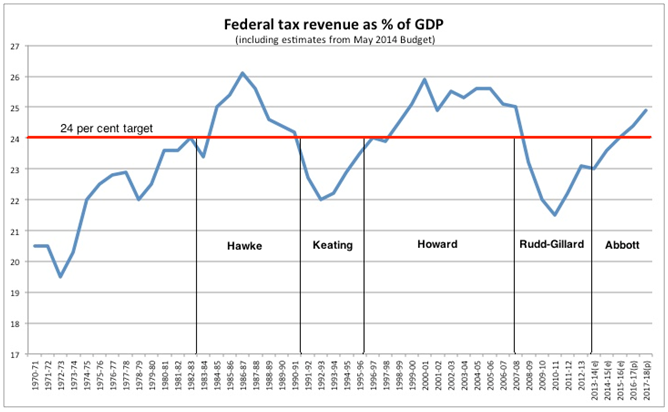

This really is where Australia now sits. As the chart below shows, federal tax revenues go up and down with economic conditions. However, the last part of the chart -- in the Abbott years -- is increasingly a fantasy.

When Joe Hockey delivered his first budget in May revenues were supposed to climb back to around 25 per cent of GDP in the next couple of years. And since the Coalition has based its fiscal plans around the 24 per cent of GDP it set as a target for the Commission of Audit (the red line on the chart), Hockey thought he would have enough spare cash to offer income tax cuts going into the 2016 election.

That's not going too well. The dramatic fall in commodity prices is flowing through to company tax revenue, which will be written down in the mid-year fiscal and economic outlook (MYEFO).

On top of that, wages growth is so restrained that Bank of America Merrill Lynch economist Saul Eslake is now warning of a possible income recession.

That would not only lower income tax receipts, but also cut off ‘bracket creep' -- in more normal times, income taxes are surreptitiously ‘raised' each year as the number of people in the top tax banks increases. A wages recession would actually produce ‘negative bracket creep'.

Once again, given this scenario, a populist left position would be “tax the rich a bit more” or “tax those corporations”.

The problem with that view is that economies are complex ecosystems, and changing one input can produce unwanted changes.

Taxing the rich might make Frank feel good, but for all he knows it could change the economy the way cane toads have changed northern Australia (not that we're comparing the rich to cane toads, of course).

In simple terms, taxing profits can be a disincentive to create new jobs through investment, and taxing incomes can be a disincentive for people with the most highly-priced skills to take on additional work.

In recent decades economists have become better at modelling complex systems, and, in fact, Britain's chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, was recently given one of the world's more sophisticated modelling systems by the UK Treasury -- a model that supported his ongoing preference for corporate and income tax cuts to stimulate the economy.

As the Telegraph newspaper reported, the model found that “... reduced corporation tax would increase the demand for labour and increase wages and consumption by £405-£515 per household. All of this will filter into the tax take, the model suggests, reducing the static impact of the tax cut on tax receipts by 45pc to 60pc in the long term”.

In the longer term, so the theory goes, the stimulus provided by the tax cuts would increase the tax take, not decrease it.

In our example, that would provide Frank with either a job, or more revenue to pay for him to attend a Tafe or university, and perhaps start a business of his own.

There's nothing new in this ‘supply-side' view of tax cuts. It underpinned ‘Reaganomics' in the 1980s. The trouble was, the zealotry with which supply-side thinking was applied led to some highly undesirable outcomes, as Alan Kohler recently described.

And the other problem with ‘cutting taxes to increase tax revenues' -- something which, by the way, even John Maynard Keynes argued in favour of -- is that it takes quite a while to work.

Australia doesn't have that long. Nor is there a clear rationale in times of a “budget emergency” for keeping the federal tax take to an arbitary 24 per cent of GDP. Both the Howard and Hawke era governments got up to 26 per cent, which is probably a better upper limit for how much tax should be gathered given the pressing need for more money in aged health care and pensions.

So to return to a theme covered yesterday, a good compromise is to keep the tax take somewhere in the 24 to 26 per cent range, and to replace some of the ‘distorting' direct taxes (income tax and company tax) with more indirect tax -- the simplest, quickest and most efficient option being a GST increase.

The Coalition clearly wants to talk Australian voters around to this view -- and raising more money for the states via GST would allow it to pay out less from federal consolidated revenue to help them meet their health and education bills.

That would leave more money to fix the budget, and would allow offsetting income tax cuts, pension and family tax benefit increases, and even better welfare or training money to get good old Frank back to work.

The big question is why Labor is not grasping the same opportunity. Telling its core voters that “you'll pay more at the shops, but you'll have more money in your pocket and more jobs in the economy” should not be too hard a sell.

However the more GST scare campaigns Labor runs, the less likely this reform is to ever see the light of day.

Sensible tax reform, free of both Reaganomic zealotry and GST scare campaigns, is the only way forward.

If the opportunity is not seized, Frank will walk to Kmart and see that the bike he wants is still the same price -- but he'll have no money to buy it, and no job to ride to anyway.