The RBA shouldn't ignore the housing market's headwinds

Increasingly lost among the monthly debate on interest rates is the Reserve Bank of Australia’s other mandate: to promote financial stability. Given the number of headwinds facing the Australian housing market, financial stability deserves even more attention than that allocated to monthly cash rate movements.

Last night in a speech at the University of Adelaide, the RBA’s head of financial stability Luci Ellis walked us through a range of issues related to financial stability since the onset of the global financial crisis.

According to the RBA, its “focus [is] on the risk of a disruption in the financial system so severe that it materially harms the real economy”, however the exact form that such disruption might take is not specified. Ellis notes that “we want to avoid financial instability because it reduces output and harms human welfare”. Ideally, policies should limit the collateral damage that occurs when credit or a business or bank collapses.

An easy way to think about financial stability is that our financial regulators try to put in place regulations to avoid events such as the global financial crisis or European sovereign debt crisis. In that regard our two financial regulators, the RBA and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority have outperformed many of their foreign counterparts.

Normally, when we focus on financial stability we look at asset prices or credit growth or our banking sector. In Australia, that often leads us down the path of discussing house prices or housing credit growth -- two issues that I have discussed in detail over recent months.

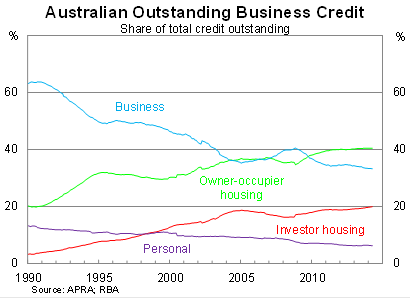

On Monday I discussed how the housing beast had starved Australian businesses (particularly of the smaller variety) over the past two decades. In fact, over the past 25 years, the share of credit allocated towards Australian businesses has effectively halved (How the housing obsession is short-changing business, June 2).

Partially offsetting this trend is that businesses are better able to tap international financial markets, which have been particularly important for our mining sector. Other large companies have also utilised syndicated lending or, to a lesser extent, corporate bond markets to finance their operations.

But regardless of international markets, the point still stands and has important consequences for economic growth but also financial stability. The sharp rise in property and land prices has increased the cost of operations and reduced the competitiveness of Australian businesses.

Ellis notes quite correctly that rising house prices can often be an affordability issue and not necessarily an issue of financial stability. But increasingly I see a housing sector that is guaranteed by a stagnant and uncompetitive non-mining sector.

How sustainable are high house prices when their success has been built on undermining the very businesses that support them? How sustainable are high house prices when they have been built on undermining income growth and squashing innovation?

I don’t necessarily prescribe to the notion that a housing bust is imminent, but I recognise the systemic risks. The Australian housing market is valued at over $5 trillion and the banks have backed it to the hilt.

The reality is that the housing market has become increasingly cyclical. Following two decades of unprecedented growth, house prices have suffered three downturns over the past decade.

These downturns occurred despite solid income growth, low unemployment and the mining boom. What would happen if the economy suffers a genuine setback, such as rising unemployment, a sharp fall in mining investment or China slowing significantly? How does a combination of the three sound?

Add in a variety of other issues such as negative real wages, university students beginning their careers with six figures of debt and an ageing population, and it becomes clear how vulnerable the Australian housing market might be.

Australia’s financial regulators have generally been ahead of the curve compared with their foreign counterparts but they appear somewhat reluctant to tackle the systemic risks created by the housing sector. It would be foolish to ignore the number of headwinds facing the property market or the implications this has for Australian banks and credit markets.