The perfect offshore allocation

Summary: You should invest offshore to diversify, but the proportion and amount of currency hedging needs to be carefully considered. The Australian dollar may be a reverse predictor of future local share market performance and the amount of hedging needed investing offshore. While currently at its market average it's pointing nowhere however its trend isn't your friend if you only invest locally. |

Key take-out: Before adjusting for extreme A$ valuations, nil-taxed and moderately taxed investors may wish to allocate one third and one half respectively of their portfolio to international shares and currency hedge one third of that. Allocate more to unhedged overseas shares when the dollar is high, and when it's low, invest more locally and hedge more. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Strategy, international investing. |

The recent superior returns from investing in offshore shares remind us all not to rely exclusively on the local share market to grow wealth. However after greater falls in both the Australian share market and the Australian dollar, it's worth asking:

1) How much of my portfolio should now be invested offshore?

2) How much of my international equity exposure should be currency hedged?

Here let me try to answer these two surprisingly difficult questions.

Why invest offshore?

Australia is a small country with a unique share market. As I have pointed out earlier (see The ASX200: A concentrated mix, September 16), our market at times is one third debt (banks), one third dirt (resources) and only one third diversified. If you are investing in index or other funds that are afraid to drift from the index supposedly in error, then you need to especially invest offshore to dilute the former two concentrations.

The Australian share market, while a good long term performer according to investment almanacs, doesn't always perform, and so accessing capitalistic rewards from offshore investments can smooth returns.

Another reason to invest offshore is to plan to profit from a falling Australian dollar but that depends on your currency hedging approach.

Why hedge your currency exposure?

Since 80 per cent of professional super fund managers believe no one can predict the movement of the currency 12 months out, this question should really be reversed: Why un-hedge any of your currency exposure?

Hedging seems especially reasonable when you learn it rewards you, it does not cost you. You are currently paid about 2 per cent annually for doing so – the amount being the difference between the Australian and overseas developed market cash rates.

Another reason for hedging is because the Australian dollar is second only to New Zealand in volatility compared to other developed countries. This causes returns to swing more with currency than elsewhere.

There are however a few good reasons why you might wish to invest without currency hedging.

Most importantly is the volatility or risk reduction achieved investing offshore expressed in local Australian dollars. The Australian dollar is a “risk on” currency and generally when “risk is off” it falls in value when overseas share prices fall. The fallen overseas share prices, when converted into depreciated Australian dollars, fall less.

An important second reason to not hedge your overseas currency exposure is to instead hedge (protect) the cost of your overseas holiday plans and local purchases priced offshore. About one third of Australian goods and services are priced offshore so arguably so at least should be your savings.

Tactically it can also pay to ride down the Australian dollar when it is unusually strong. That was important from when it peaked at $US1.10 in 2011/12 at the end stages of the commodity boom and during the orchestrated US currency devaluation. Conversely it is also important to have more hedging once the Australian dollar becomes especially weak – like when it was US50c during the late 1990s Asia Crisis and early 2000s recession.

If so, how much?

According to finance theory, the optimal amount of international equity exposure and the amount of currency hedging can be determined by minimising portfolio volatility. Many investors have a capped capacity for downward portfolio fluctuations due for instance to behavioural reasons or to manage pension funding longevity. Accordingly they have a capped capacity for equities which limits long-term returns. The theory goes, the more you can limit volatility, the more equities you can stomach and the more returns you can expect.

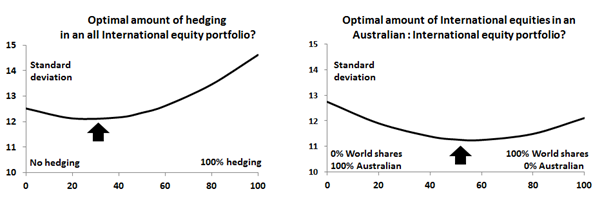

Figure 1 suggests that the optimal amount of international equity currency hedging is one third, and with that in place, a 50:50 Australia:international share mix is optimal. It offers an elegant answer but it's sadly not always that simple.

Figure 1: Standard deviation of all equity portfolio returns: (left side) varying the per cent amount of currency hedging in an all World ex-Australia portfolio; and (right side) varying the per cent amount of World ex-Australia shares in an Australian : World ex-Australia portfolio (one third hedged), based on 20 year index returns to October 31, 2015. Source: Professional Wealth

Real world experience

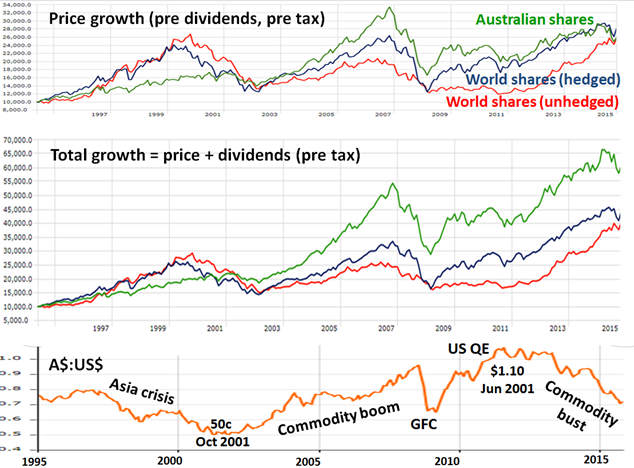

The last 20 years is a convenient time to look at local and offshore share returns as the Australian dollar conveniently started and finished at about 70 cents to the US dollar. Figure 2 depicts the price growth and total return counting dividends, investing $10,000 in the Australian share market (shown in sporty green), World ex-Australia share markets (raw and wild in red, and in patriotic blue after currency effects are hedged out). The differences between the red and blue lines are driven by the oscillating Australian dollar's value, shown against the US$ in the bottom in orange. Foreign investments are perhaps half linked to the US dollar so this isn't the only driver.

Figure 2: Growth of $10,000 invested in Australian shares (ASX200, shown in green) and World ex-Australian share markets (shown in red in A$ terms unhedged and in blue after hedging used to eliminate currency changes). Shown in orange below is the changing AUD:USD rate.

You should see that on price alone, $10,000 would have nearly tripled over 20 years, regardless of which investment was chosen … which makes financial theorists pleased. However counting reinvested dividends shown in the middle chart (though not hedging income not included in this index), the Australian share market outperformed.

The Australian share market didn't always outperform. It underperformed in the first five years as un-Australian dotcom shares took off and we became collateral damage in the Asian crisis. In the next two to three years most dotcom gains were proven illusory which meant the Australian share market outperformed by not falling much in the 2000 recession. Then we really outperformed as China and commodities boomed – until the GFC struck. While not easily seen, the fall in unhedged World shares was only minus (30) per cent compared to minus (50) per cent for Australian and World shares currency hedged. Since 2011 Australian shares have lagged international shares, especially if counted in unhedged Australian dollars.

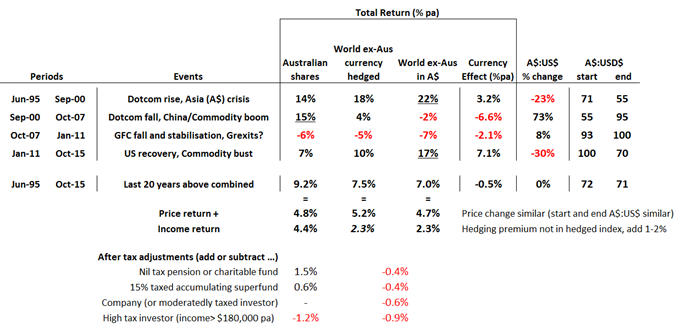

The below table summarises these four periods. After considering the rise and fall of example resource company BHP (from $7 to $43 to $20) and the rise and rise of example bank CBA (from $7 to $75), I think we can conclude the 2 per cent outperformance of the Australian share market is probably entirely due to bank share prices – that and their generous dividends increasing 10x.

I doubt you can count on that again, and so you can't count on the Australian share market always outperforming. If you are looking for extreme returns, they are often found in unhedged World equities when the Australian dollar is falling.

Tax considerations

While I am happy to expect that total future pre-tax returns from local and international shares should be the same (the local variant simply offering higher income, but probably lesser reinvested/funded growth), I am not happy to say a local investor earns the same after tax.

As shown in the earlier table, nil locally taxed, including super pension and charitable fund investors, earn about 1-2 per cent more investing in Australian shares than international shares because of dividend imputation – a refund of company tax paid. Accumulating super fund and other low taxed investors earn about half this extra return. After that, comparative returns are tax neutral. Technically high taxed investors benefit more from investing in fast growing, low dividend paying international shares but they can do that too buying CSL not CBA. Note locally nil taxed investors have dividends taxed offshore through withholding (example 15 per cent rate), which they don't get back nor can offset. This reduces after tax returns from international investing, widening the gap.

Franking credits and foreign tax mean that nil taxed domestic investors should invest less offshore.

They shouldn't invest solely locally as 1) there are periods like now where returns can suffer and 2) they can make up for some of this with currency hedging income. I'm inclined to put my finger in the air and say that nil taxed pension and charitable fund investors should perhaps allocate 60:40 or 2:1 in Australia:international shares, not 50:50 (1:1).

Active allocation?

If over the last 20 years you only made two investment allocation changes to your all equity portfolio you could have earned 13 per cent not 8-9 per cent annually, and doubled your money, even despite the GFC. That would have been from investing solely in international shares during the dotcom boom, being out of Asia crisis-affected Australian shares, then when vapourware dotcom returns looked to evaporate, you switched solely into Australian shares in 2000; then again in early 2011 when the US looked to be on its feet and China and Australia less so, you switched back entirely into unhedged international shares.

Of course this is easy to say in hindsight. True but you had to look at only one signpost: the Australian dollar. The first switch was in year 2000 near when the dollar troughed at US50c and 2011 was close to its $US1.10 peak. The Australian dollar follows or perhaps reversely predicts the future of our share market and perhaps all you need to do is follow it?

This lastly leads me to the important question about tactically adjusting your international share mix and hedging strategy. With the Australian dollar largely at its long term post-float average value, it may make sense to return your settings to the benchmarks suggested here (one third hedged and half or one third in international shares if you are a taxed or tax free investor respectively).

Should the Australian dollar fall further, that supports increasing your mix of bargain priced Australian shares and the amount of currency hedging applied to your remaining international equities.

Dr Douglas Turek is Principal Adviser with independently owned, family wealth advisory and money management firm Professional Wealth (www.professionalwealth.com.au).