The oil price slump could be toxic for markets

As the OPEC meeting in Vienna looms, all talk is on whether members will agree to cut back production to halt falling oil prices.

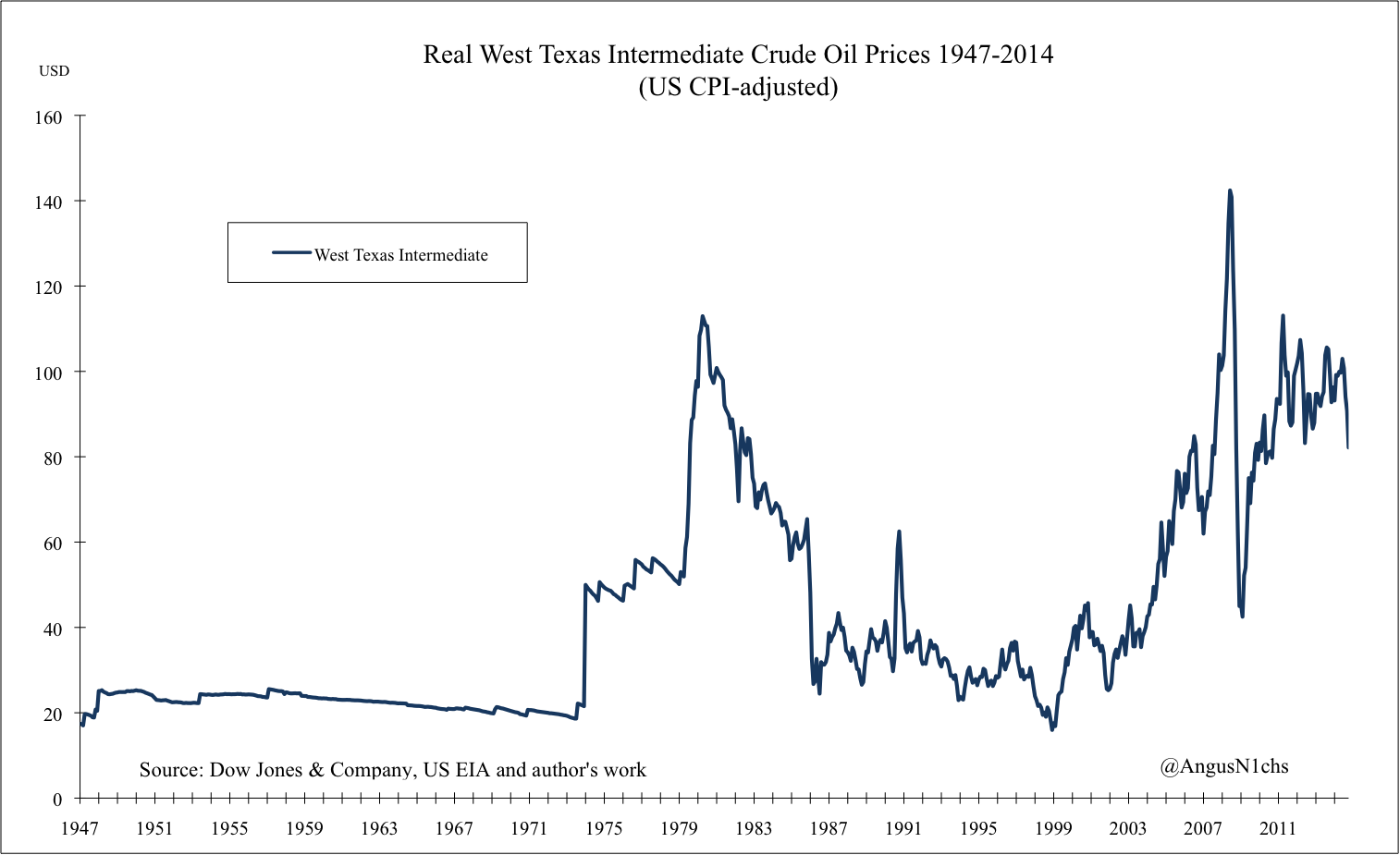

Oil prices have been steadily declining since June, with both Brent and West Texas Intermediate prices dropping from over $100 a barrel to the mid-$70 a barrel region.

After almost three years of oil prices hewing closely to the $100 a barrel level, it looks like the large amounts of new supply that has come on-stream and the slowing global growth has created a new oil glut, and analysts are predicting prices may fall into the $60 range. The surge in US crude oil output associated with the 'shale revolution' in North Dakota's Bakken and Texas's Eagle Ford structures, has left suppliers looking for new markets.

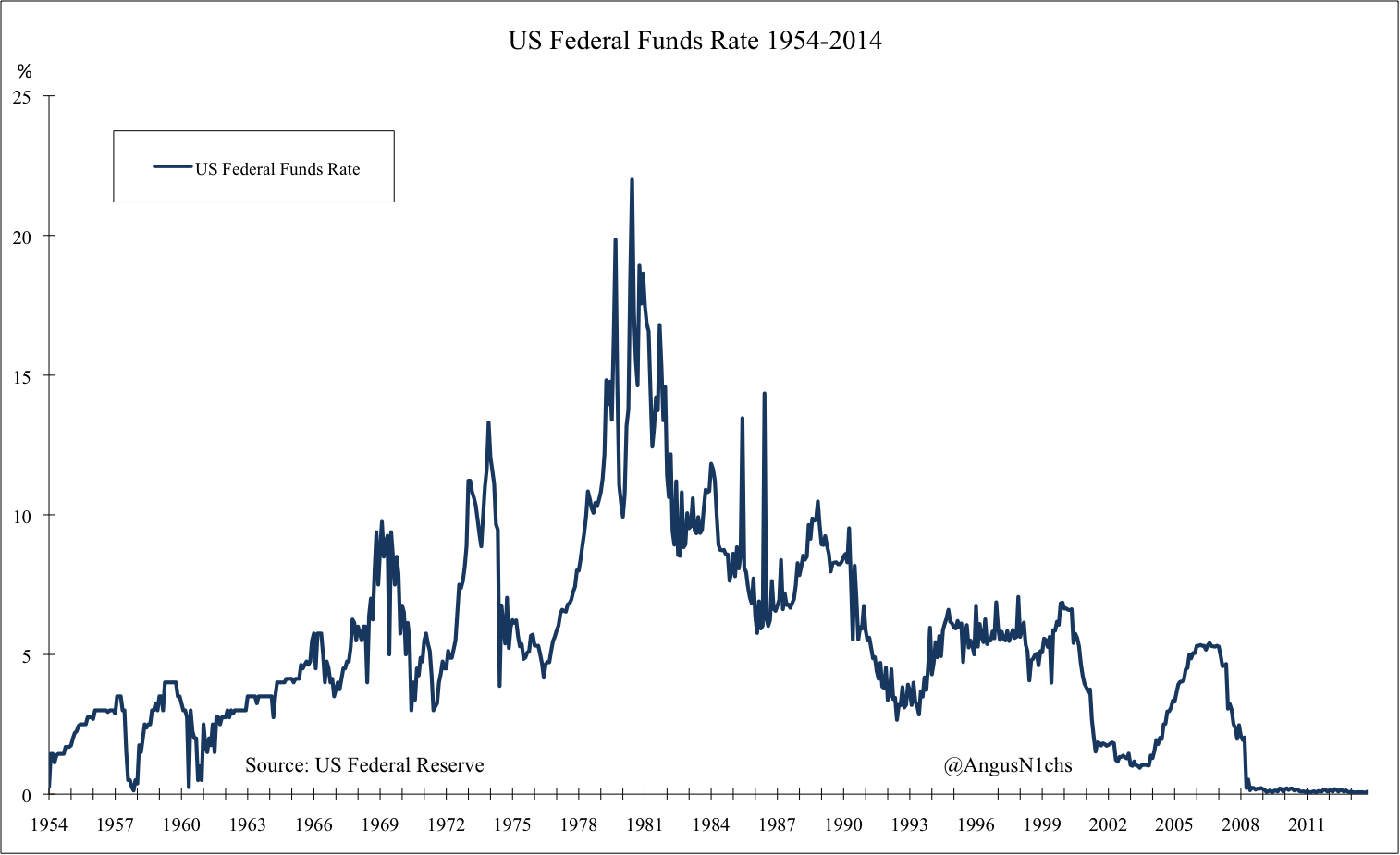

Europe is teetering on dipping into another recession, Japan just entered a technical recession in 3Q and China is resolutely trying to keep financial imbalances in check as its growth rate slows. Meanwhile, the US Fed is preparing to raise rates setting the scene for a potential multi-year US dollar bull market.

The falling oil price and the China slowdown is particularly affecting those countries reliant on commodity exports like Russia, Iran, Indonesia, Brazil and South Africa. Some have argued that Saudi Arabia has been forcing prices down to hurt Iran and ally Russia over their support for the Assad regime in Syria, while others have said they have simply been forced to accept lower prices to compete with new supplies.

As yields have come down with the Fed's QE policy, investors have sought out risk in high-yield products.

Energy companies have been a major supplier of these speculative high-yield bonds. Energy bonds now account for 15.7 per cent of the entire $1.3 trillion junk bond market up from 4.3 per cent a decade ago. As the oil price drops further and the spreads on energy bonds continue to widen, there are fears that a wave of defaults and restructurings could spread through the energy sector and we could see a crisis like the 1980s.

The sizable OPEC price hike in the wake of the 1973 Yom Kippur War had led to a steady increase in oil prices, creating a massive inflationary impulse in the world economy. Throughout the 1970s, the oil market was straining ever higher as the aggressive exporters in OPEC, Libya and Iran, constantly pushed for higher prices. Saudi Arabia, the conservative of OPEC, believed prices had become too high and were not only hurting global growth, which would hurt demand, but also making new technologies and expensive oil plays increasingly viable, providing further supply and greater competition to Saudi Arabia itself.

Yet these events were taking a toll on Iran, and the Shah of Iran was beginning to lose his grip on power in 1978. As Daniel Yergin recounts in The Prize: “Iran simply could not absorb the vast increase in oil revenues that was flooding into the country. The petrodollars, megalomaniacally misspent on extravagant modernization programs or lost to waste and corruption, were generating economic chaos and social and political tension through the nation.” Reza Shah's position became untenable, and he fled the country in January 1979. Ayatollah Khomeini returned thereafter and Iran became an Islamic Republic in April 1979.

As Iranian oil production dried up in 1978, Saudi Arabia and other OPEC countries stepped up production to try combat the price increases. They managed to contain price increases in early 1979, but they went on a parabolic run after the establishment of the Islamic Republic. The halting of Iranian production produced a shortage of world oil output, which produced the initial panic.

But as Daniel Yergin recounts, the Iranian revolution also disrupted pre-existing oil contracts. There was a rush of new buyers into the marketplace looking to lock up new supplies, oil exporters saw it as an opportunity to capture enormous rents, and there were fears that this Iranian Revolution could repeat itself across the Middle East. Panic fired up the market, as buyers fearing a repeat of 1973 made the shortage worse by building up huge inventories far beyond any reasonable expectations of consumption.

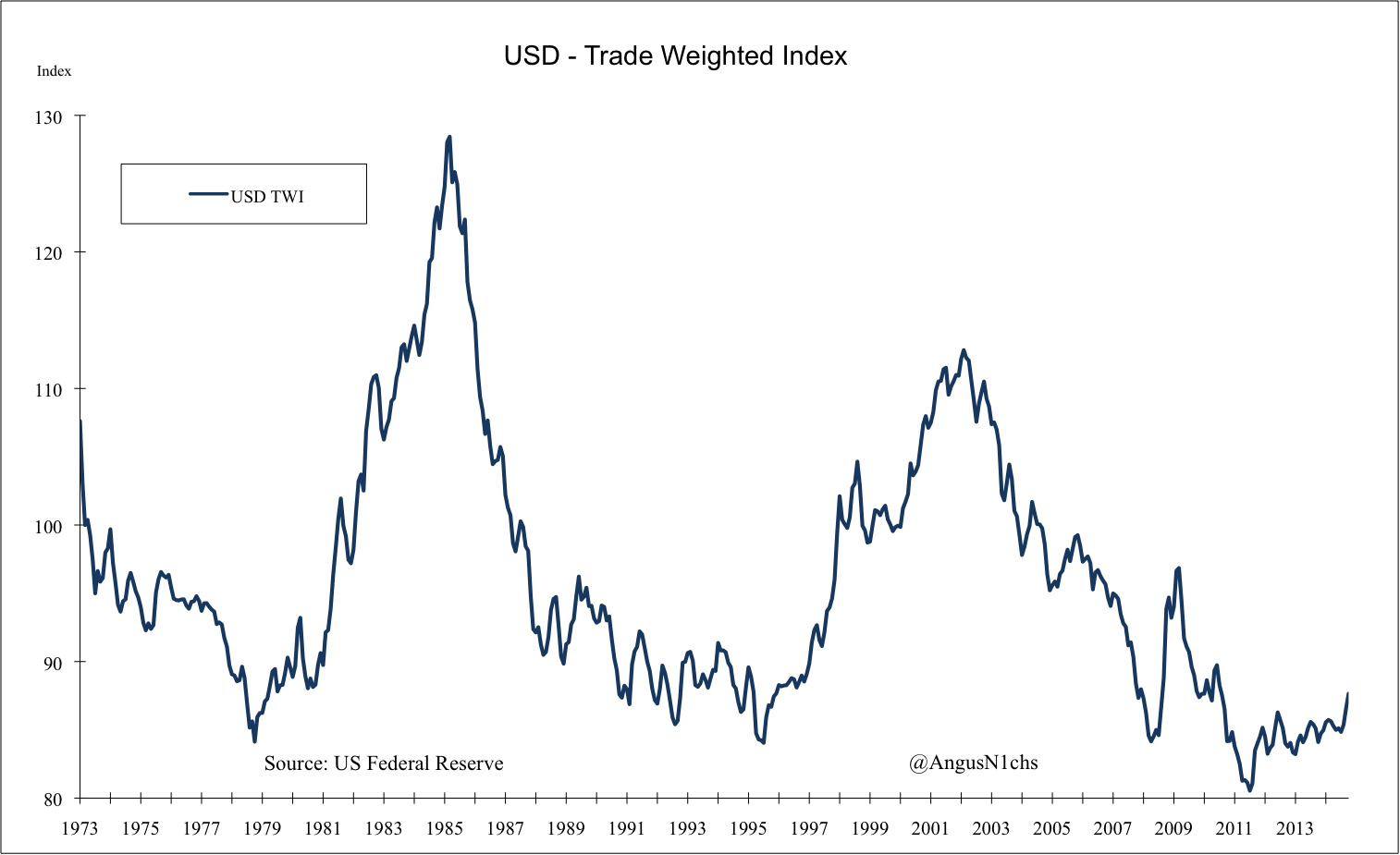

This led to double-digit inflation in the US. The then Federal Reserve Chairman, Paul Volcker, had to resort to dire measures to get inflation under control and began hiking the federal funds rate, which peaked at 21.5 per cent. This led the US dollar to go on a record run, with the USD Trade-Weighted Index rising from 88.9 at the start of 1980 to a peak of 128.4 in March 1985.

The incredible oil boom of the 1970s had led to untold riches. Oil companies plowed revenue into new explorations and leveraged themselves up to the hilt from banks and eager investors. Large new reserves in the non-OPEC world put new supply on the market, with major new developments in Mexico, Alaska and the North Sea joined by new exporters such as Egypt, Angola, Malaysia and China. Emerging markets also benefitted enormously from the recycling of huge petrodollar reserves accumulated by oil exporters, leveraging themselves up on foreign-currency denominated debt.

This cycle began to painfully unwind itself. The Fed's rate hikes strained the financing on heavily leveraged companies engaged in projects based on lofty oil price projections. The high rates drew in capital from around the world leading to the US dollar's steady rise, significantly raising the burdens on countries with US dollar-denominated debt, which was even worse for countries who relied on oil exports for their FX earnings. And the costs of keeping all this oil stored in inventories became completely uneconomical and a huge amount of supply was steadily dumped onto the market, pushing oil prices down even further. This developed into the worst recession since the Great Depression, with the first dip coming in 1980 and the second much more severe one in 1982, contracted demand for oil further.

US lenders had also been readily supplying credit to the energy sector with little concern for caution. One of the most aggressive lenders to the energy sector had been the little-known Oklahoma bank, Penn Square. It amassed a huge portfolio of oil and gas loans that they sold on to bigger banks, with Continental Illinois, the seventh-biggest bank in the US, being a major buyer. Penn Square was totally insolvent and regulators shut it down, but Continental Illinois held a systemic threat to the US financial system.

As Gary Gorton recounts in Misunderstanding Financial Crises, the collapse of Continental Illinois could have led to other bank runs and a potentially major financial crisis. The decision was made to undertake the largest ever US bank bailout at the time, with the government guaranteeing all accounts and effectively nationalising the bank.

Whatever is decided at the OPEC meeting, oil prices are set to decline further. And, with the Fed signalling rate hikes for next year, and with continued QE in the rest of the world, the US dollar looks set for a multi-year bull run. This turn of events entails many risks for the energy bonds and USD-denominated foreign debt. In these times, it is worth remembering the ghost of Continental Illinois.

Angus Nicholson is graduate of the School of Oriental and African Studies, and is a Master's candidate at the ANU for 2015. Follow him on Twitter at @AngusN1chs.