The low inflation pill gives the US a boost

Inflation remains benign in the US but the oil price creates a significant risk to the near-term outlook. Nevertheless, the US economy appears to be in reasonably good shape and is poised to end the year on a high note.

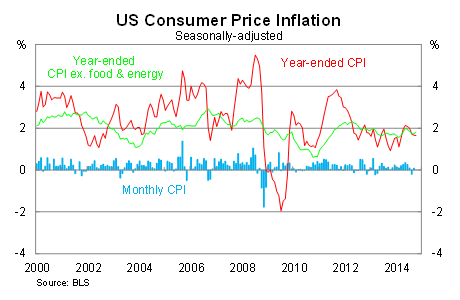

In the US, headline inflation was unchanged in October, beating market expectations, to be 1.7 per cent higher over the year. Inflation has moderated somewhat over the past three months and remains considerably below the Federal Reserve's target for 2 per cent annual inflation.

But there is tentative evidence that inflation pressures are firming. Core inflation -- which excludes volatile items such as food and energy -- rose by 0.2 per cent in October, to be 1.8 per cent higher over the year. Although it is dangerous to put too much faith in a single month, it's worth noting that this was the strongest result since May.

Energy prices fell by 1.9 per cent in October and are now down 5.4 per cent since June. Although the decline in oil prices has weighed on headline inflation -- creating a mirage of weakness -- it has supported household spending and has acted as a de facto wage rise.

Unfortunately the rise in purchasing power has been eaten away by higher food and housing costs. Food and beverage prices rose by 0.1 per cent -- easing somewhat compared with the past eight months -- to be 2.9 per cent higher over the year. Housing costs rose by 0.2 per cent in the month.

Oil prices present one of the clear risks to the US economy and the inflation outlook. First, if oil prices tick lower and stay there for a prolonged period a number of oil investment projects in the US will be at risk. Second, if oil prices stabilise then headline inflation will head towards the Fed's upper target.

The near-term risks to the oil price potentially lie on the upside. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) -- the oil cartel -- is meeting in Vienna this week to discuss whether they should cut production.

Nevertheless, inflationary conditions are largely benign and will remain that way even if energy prices begin to rise. This can be explained by examining two factors: wage growth and the US dollar. A third factor -- the end of the Fed's asset purchasing program -- may also weigh on prices, but at this point it's too early to say.

Despite strong employment growth -- non-farm payrolls are on track for the strongest year since 1999 -- wages have not followed suit, reflecting a surge in low-wage and part-time work. Real average hourly wages increased by just 0.3 per cent over the year to October (An inflating dampener on US rate expectations; November 10).

A stronger US dollar and deteriorating global growth expectations will continue to weigh on import prices and headline inflation into early next year. That said the effect shouldn't be that great given the US is less trade-exposed than other developed countries, with a range of goods traded internationally in US dollars.

Other measures of inflation provide a somewhat conflicting view of the US economy. The Cleveland Fed's measure of median inflation rose by 2.3 per cent over the year to October, while its trimmed-mean measure rose by 1.9 per cent.

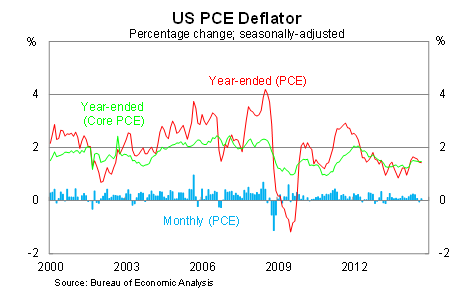

Those measures suggest that a rate rise should be imminent but it's the personal consumption expenditure deflator which is giving the Fed pause. The core PCE deflator -- the Fed's preferred measure of inflation -- rose by 0.1 per cent in September, to be 1.5 per cent higher over the year.

Until the core PCE deflator begins to firm, the Fed is unlikely to hike rates. Eventually I expect the core PCE deflator and the other measures of inflation to converge; I also expect strong employment growth to flow through to higher wage demands. However, there remains considerable uncertainty and neither the market nor the Fed have a good feel for when these factors will warrant a rate hike.

My position is that if the unemployment rate drops to, say, 5.5 per cent by March next year (currently it's at 5.8 per cent) then the Fed may feel the need to act, even if wages and inflation have yet to react.

But a lot can happen between now and March; for now, the Fed will simply be happy that the US economy continues to create a high number of jobs each month and that the market seems to have coped with the end of the Fed's asset purchasing program.