The housing market is on shaky foundations

| Summary: Weaker bank lending and a decline in housing turnover indicate that the housing market isn't quite the all-conquering beast that it once was. |

Key take-out: Investing in the property market is potentially more risky right now than at any period since the global financial crisis. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Property, strategy. |

In recent months there has been some confusion surrounding conditions in the Australian housing market. Some measures, for example, suggest that dwelling prices continue to rise at a strong pace; other measures suggest that conditions have soured somewhat as new mortgage lending has deteriorated.

The weight of evidence suggests the latter. House price growth has moderated on the back of weaker bank lending and a decline in housing turnover. Conditions outside of Sydney and Melbourne have been weak for a number of years, while first-home buyer (FHB) activity remains disappointing.

Low interest rates and the prospect of further rate cuts provide some upside for capital gains down the track. However, rental yields remain low with newly negotiated rents falling across the country. It's also worth remembering that low interest rates haven't been sufficient to boost prices outside of Sydney and Melbourne.

Investing in the Australian property market is potentially more risky right now than at any period since the global financial crisis. The big capital gains are likely over – at least for a few years – and investors should bear that in mind as they consider investment opportunities.

Dwelling price methodology

Calculating the change in dwelling prices across a capital city or nation is fraught with complications and certainly more difficult than you might realise.

It is not enough to take a simple median or average of the sales that occur in a given month or quarter. Simple measures such as these are prone to compositional bias, which occurs when there are changes in the size, location or quality of properties sold between periods. This results in high levels of volatility, which makes it difficult to separate movements that are meaningful from those that aren't.

A good example of this phenomenon occurred following the onset of the GFC. Federal and state governments implemented a range of rather generous grants for FHBs. This triggered a sharp rise in first-home owner activity.

For a simple median or average dwelling price measure, a sharp rise in FHBs could potentially lower dwelling prices since FHBs tend to buy houses or units that are cheaper than the average or median dwelling. This occurs despite the fact that government grants boosted the price of most homes sold during that period.

As a result we need more sophisticated measures that account for changes in the composition of properties sold across periods. Australia has a range of these measures – more than most countries actually – with each using a different methodology.

Usually these measures tells a broadly similar story but sometimes there can be a divergence, which creates some confusion. Since dwellings account for a majority of household assets and liabilities, this can prove problematic for policymakers.

Until recently the preferred measure of dwelling prices for the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) was the CoreLogic hedonic measure, which models house prices based on a range of variables (such as location, number of bedrooms, etc) to control for changes in composition.

This measure shifted to a daily methodology a few years back and has slowly fallen out of favour. Dwelling prices are difficult enough to measure on a month-to-month or quarter-to-quarter basis without trying to construct a daily index. More recent changes in methodology were addressed by the RBA during its recent Statement on Monetary Policy.

“Recent information suggest that the strong increases reported by CoreLogic were overstated as a result of methodological changes affecting growth rates in the June quarter,” the RBA said.

In response the RBA has placed greater emphasis on other measures such as those from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and Australian Property Monitors (APM).

These measures utilise what is called a ‘stratified median' approach. This involves separating each capital city into postcodes and then allocating those postcodes to 10 separate buckets determined by how expensive those postcodes are. It then takes the median price for each bucket based on transactions during the period and applies a geometric mean to create a compositionally-adjusted price measure for each capital city.

Both methodologies might sound complicated but they typically do a good job of reducing monthly or quality volatility, ensuring that price growth reflects actual changes in prices rather than the type of properties sold.

Recent developments

The ABS released its dwelling price measure this week and it confirms the RBA's belief that conditions in the housing market have deteriorated somewhat.

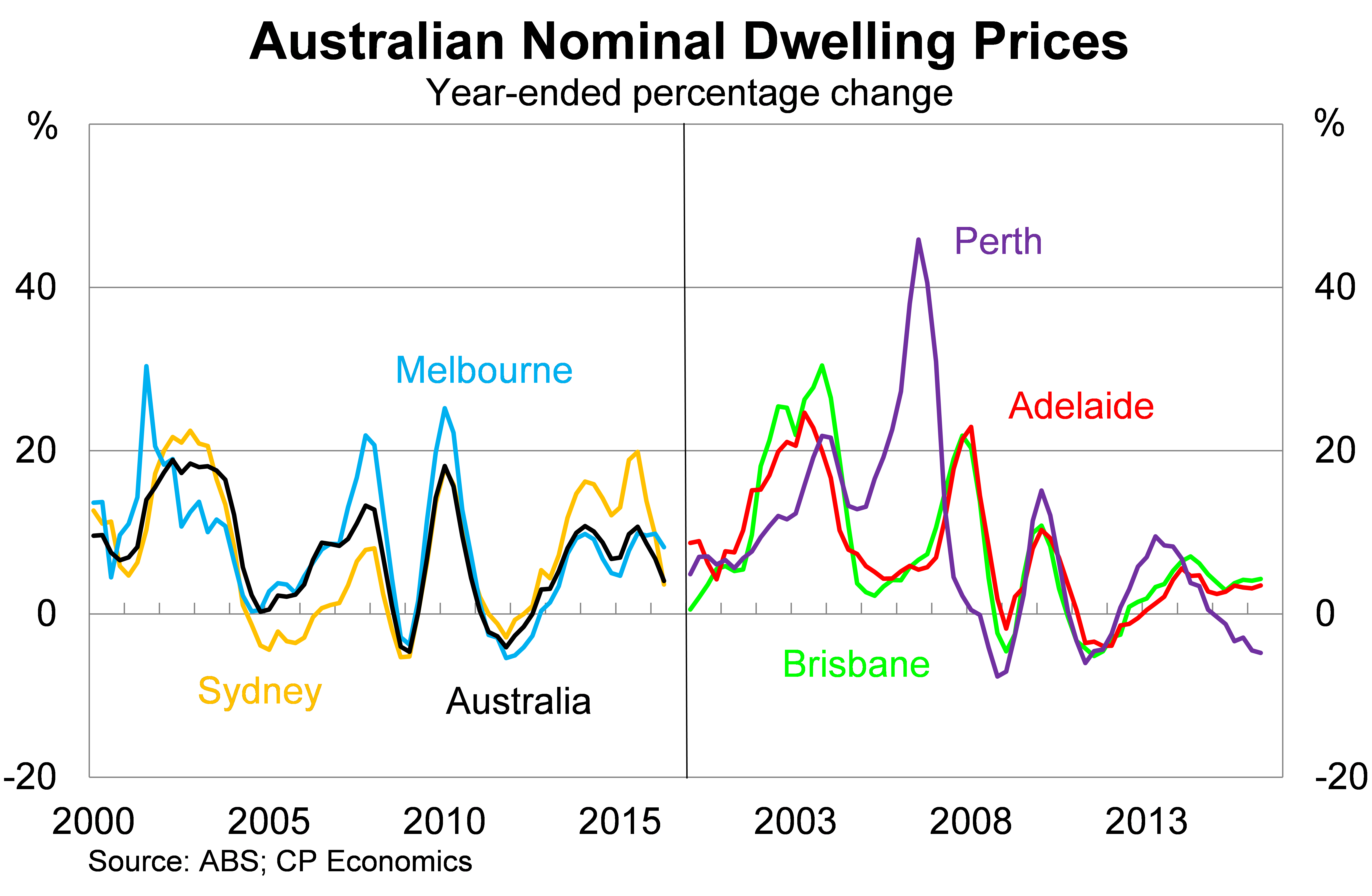

According to the ABS, house prices rose by 2 per cent in the June quarter, following a modest decline in the March quarter, to be 4.1 per cent higher over the year. Prices in Sydney rose by 2.8 per cent, following two consecutive quarterly declines, while prices in Melbourne rose by 2.7 per cent. Prices continue to fall in Perth.

Growth in Sydney and Melbourne has slowly begun to converge with price growth across the other capital cities, with the obvious exception of Perth where conditions are much weaker.

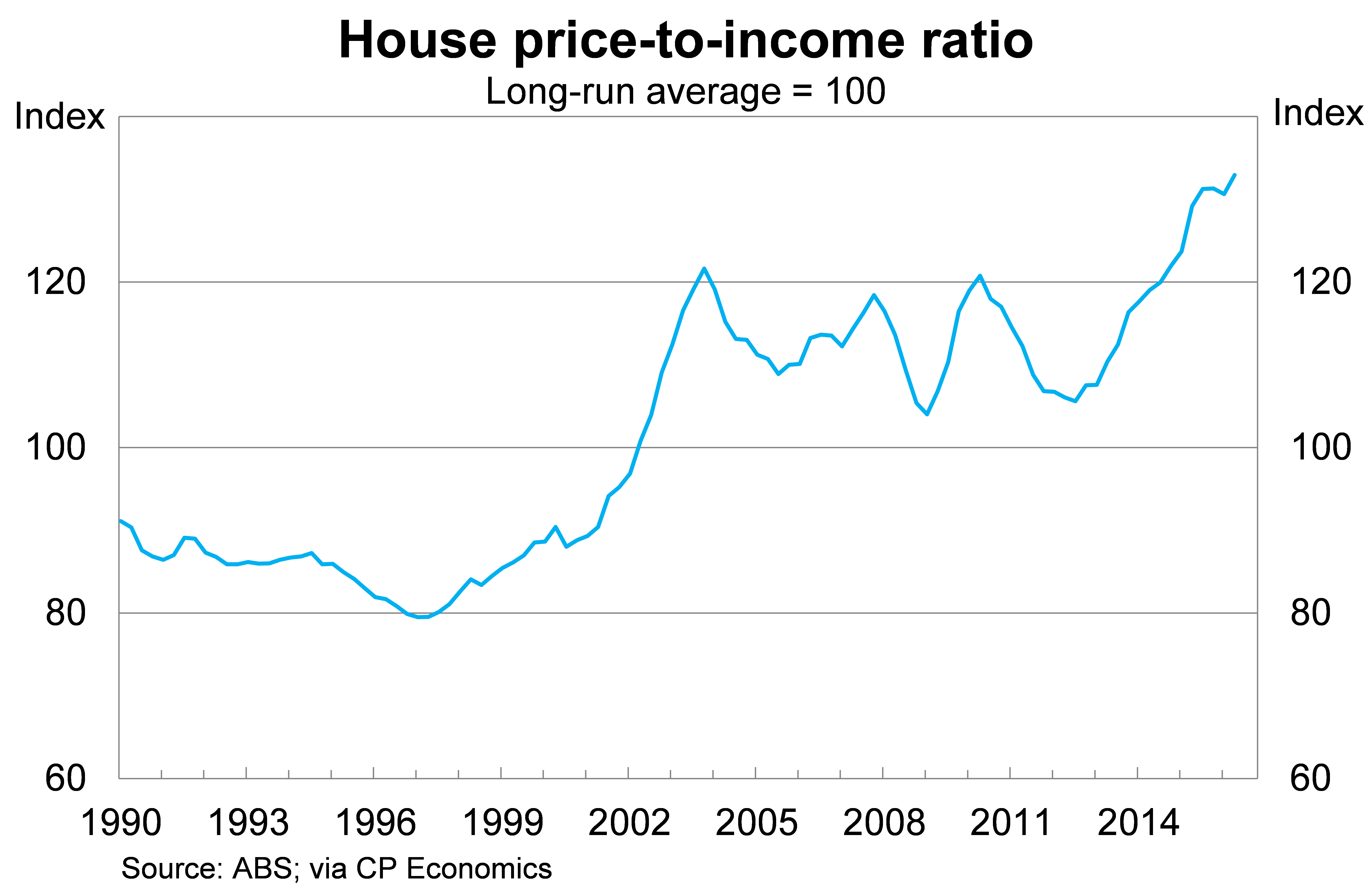

Housing multiples, which are a simplistic but useful proxy for affordability, show that housing is expensive by historical standards. The house price-to-income ratio is currently at its highest level on record while rental yields are currently around their lowest level in history.

This can partly be explained by historically low interest rates but we can see from the graph below that there is a tendency for the market to correct once the house price-to-income ratio reaches an elevated level. It'll be interesting to see how long national house price growth can exceed growth in household disposable income and how large the inevitable correction is.

Low interest rates have helped to reduce the interest burden on households and investors in recent years. However, the biggest challenge for FHBs remains the deposit to enter the housing market. It has been impossible in recent years to save enough to keep up with house price growth in the likes of Sydney and Melbourne. Low interest rates actually exacerbate this problem by undermining our ability to save.

Despite an elevated house price-to-income ratio, there is a compelling argument that the property market really isn't that strong.

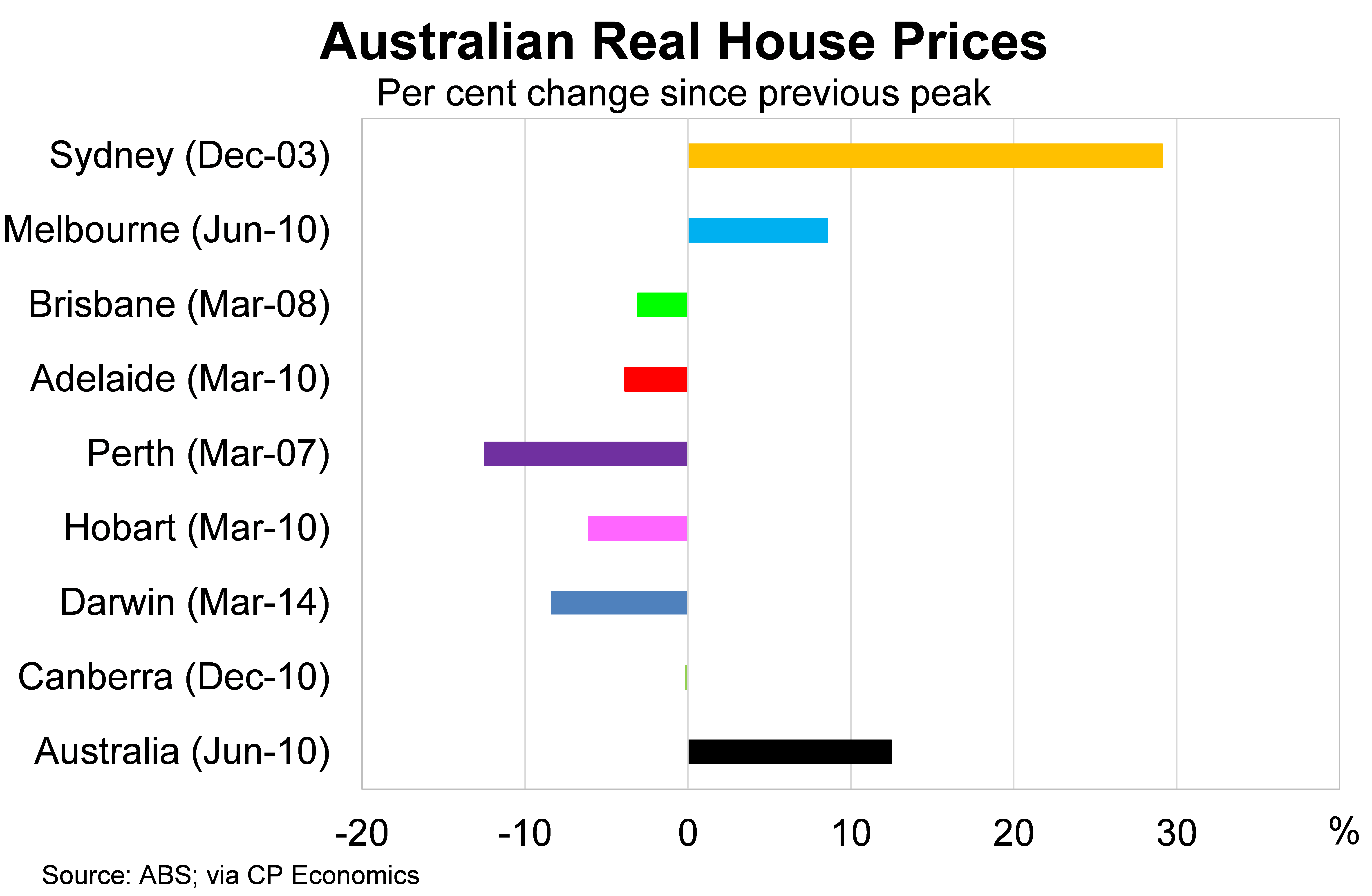

After adjusting for inflation, dwelling prices across most capital cities are below their earlier peak. I've touched upon this before but it's worth updating for the new set of data (The pressure is rising on Aussie property, August 2).

Dwelling prices in Perth are 12.5 per cent below their peak in the 2007 March quarter. Prices in Brisbane are 3.1 per cent below their peak back in the 2008 March quarter.

Dwelling prices in Sydney are 29 per cent above their peak but that peak occurred all the way back in the 2003 December quarter. Sydney – despite the recent boom – has experienced real annual growth of just 2.1 per cent a year over that period (though to be fair, real annual growth averages to 10.4 per cent over the past three years).

The figures indicate that the Australian housing market isn't quite the all-conquering beast that it once was. The housing market has been characterised by regular weak-spots over the past decade. Even Sydney has experienced long periods of soft growth or outright declines.

Property investment can still be quite attractive given the combination of low interest rates, favourable tax incentives and rental income. It's even attractive for owner-occupiers given the family home is not subject to the capital gains tax. Many investors have made out quite nicely in the past few years as Sydney and Melbourne prices boomed.

But the recent turn in the market, confirmed via softer mortgage lending and reduced turnover, suggests that this boom has come to an end. Investors getting into the market right now have missed the boat and may need to wait a number of years before they experience positive capital gains.

Investors focused on long-term capital gains may be fine with that risk but other investors may find value in waiting for the house price-to-income ratio to return towards more sustainable levels.

Value investors may find some appealing investment opportunities outside of Sydney and Melbourne, since price growth outside those cities has underperformed for a number of years.