The housing 'glass half full' is leaking

A major new report from the Centre for Independent Studies, released today, is a thorough examination of the housing ‘myths’ that suggest the Australian housing market is out of kilter with economic fundamentals.

While many myths are examined, the fundamental argument is that lack of adequate supply in the housing market relative to a growing population, has resulted in Australians bidding more vigorously for the better housing stock – including the supply of larger or more highly renovated houses.

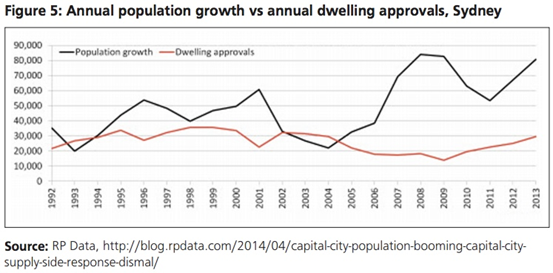

The chart below shows the under-supply argument, which has been made frequently by a number of commentators.

That imbalance has, according to the ABS, meant that households are forced to pay more for accommodation.

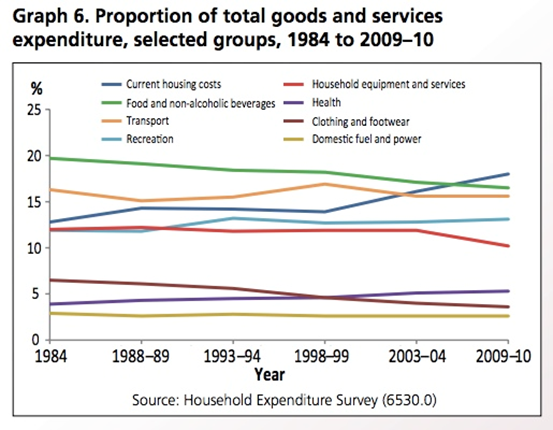

The ABS notes in a recent report: “Consumption patterns of households have changed since 1984. Current housing costs increased from 13 per cent of total household expenditure on goods and services in 1984 to 18 per cent in 2009–10.”

As seen in the ABS chart below, that has meant that while food and non-alcoholic beverages, clothing and footwear, household equipment and services have fallen in relative terms, the amount we spend on rent or mortgages has become more obviously painful year after year.

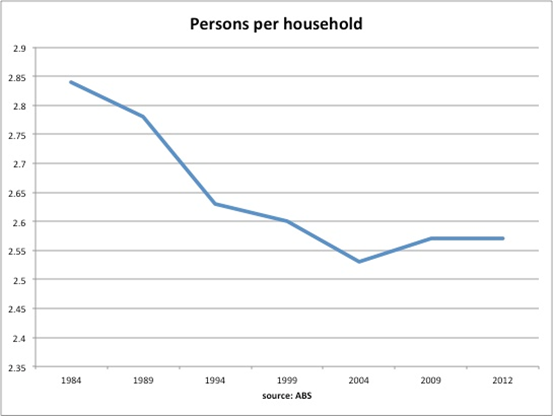

This has not been helped by the trend, until mid-way through the Howard years, of the number of people per household falling (see chart below).

There are signs of that trend stabilising, and as suggested earlier in the week there may be some big changes in patterns of habitation if Abbott government reforms – particularly the cutting off of dole payments for many under-30s – somehow get through the hostile Senate (Trouble in the bedroom for housing investors, July 4).

The tenor of the CIS report is summed up by its insistence that: “In Australia, the long-run appreciation of real house prices, as well as their short-run variability, is empirically well explained by economic fundamentals and is entirely consistent with expectations derived from economic theory.”

The main problem with that point of view is that it is an ‘all things being equal’ position.

The report correctly notes that Australian incomes have risen strongly during the period in which house prices have grown an average of 3 per cent ahead of inflation since 1970 – yep, that would be consistent with bidding up house prices.

It is also true that during that period participation rates have risen due to the long-term social change of greater numbers of women entering the workforce – again, a theory that is consistent with high prices.

However, given the turn in the terms of trade associated with long-term lower resources prices, an ongoing problem with under-employment particularly in younger age groups, and a long-term structural problem with workforce participation as the baby boomers retire, there is really no reason for the parameters of the past to support such high prices into the future – unless high levels of immigration are used to put a floor under stalling demand.

The CIS is probably right that stellar prices are “entirely consistent with expectations derived from economic theory”. But going forward any expectation that ongoing price rises of 3 per cent above inflation can be sustained is too optimistic.

Put another way, the ‘all things being equal’ argument will founder on an economic future in which trend of the past are reversed – likely higher numbers of persons per household, lower rates of real income growth and, as the report hopes, better supply responses in the form of expedited land releases and planning approvals.

Or will it be a glut of inner city apartments that tips the balance?

Overall, the CIS argument will be welcomed by a government desperate to keep up some of the wealth effect seen during the Howard/Costello years, when paper profits and home equity withdrawal added buoyancy to consumption.

It will also be welcomed by banks who wish to continue to expand their mortgage assets in times of sagging consumer and business confidence.

But the report’s findings will not get a good reception with first-home buyers priced out of the market, or those in lower income groups who notice most that 18 per cent of disposable income spend on housing feels very different to the 13 per cent Australians paid three decades ago.