The good news on Brexit

Summary: Global share markets have been rattled by the prospect of a leave vote in Thursday's UK referendum, but Australia is well placed to weather the storm regardless of the outcome, given our exports to Britain are now minimal. Last week's Aus market data indicates our ability to create full time, high quality jobs is sliding. |

Key take out: Softer work participation numbers are trouble for investors because they mean a smaller group of Australians are working to replicate past company performance. |

Key beneficiaries: General Investors. Category: Economics and investment strategy. |

This week I wanted to touch upon three issues that are important to Australian investors. The “Brexit” decision has important near-term implications; the Australian labour market underpins the performance of Australian equities; and China's economic transition will play an important role in Australia's economic performance over the next decade.

Brexit

With just days remaining until Thursday's pivotal EU referendum to determine whether the United Kingdom will remain or leave the European Union, the campaign to stay in the union has taken a modest lead. That's great news for global investors.

The so-called “Brexit” has been a complicated and often nasty affair. The social and political issues are deeply complex; nothing involving the European Union is ever as simple as it should be. The economic case, however, has always been pretty clear cut: leaving the EU would be devastating for the UK economy.

According to the International Monetary Fund, a vote to leave the EU could wipe as much as 5.5 per cent off real GDP by 2019. That's massive. If the IMF is correct the UK could very well be looking at another recession and a downturn that would unwind much of the improvement that has taken place over the past few years.

The IMF isn't alone with the pessimism. The Economic Intelligence Unit, an offshoot of The Economist, estimates that a Brexit could reduce real GDP by six per cent by 2020. Almost without exception the conclusion is that a Brexit will be devastating for UK economic interests.

The mere prospect of a Brexit, with opinion polls last week pointing to a victory for the “Leave” campaign, was enough to drive the sterling and global share markets lower. Market moves early this week will be driven, to a large degree, by shifts in polling leading up the referendum on Thursday.

According to some forecasts, the sterling could drop by between 15 to 20 per cent in the event of a Brexit. Households will be hit by higher import prices, including fuel, and overseas tourism will become more expensive. There is also speculation that a weaker sterling could prompt the Bank of England to increase interest rates. That is unlikely though given that any spike in inflation resulting from leaving the EU will be viewed as temporary; an event that does not require higher interest rates.

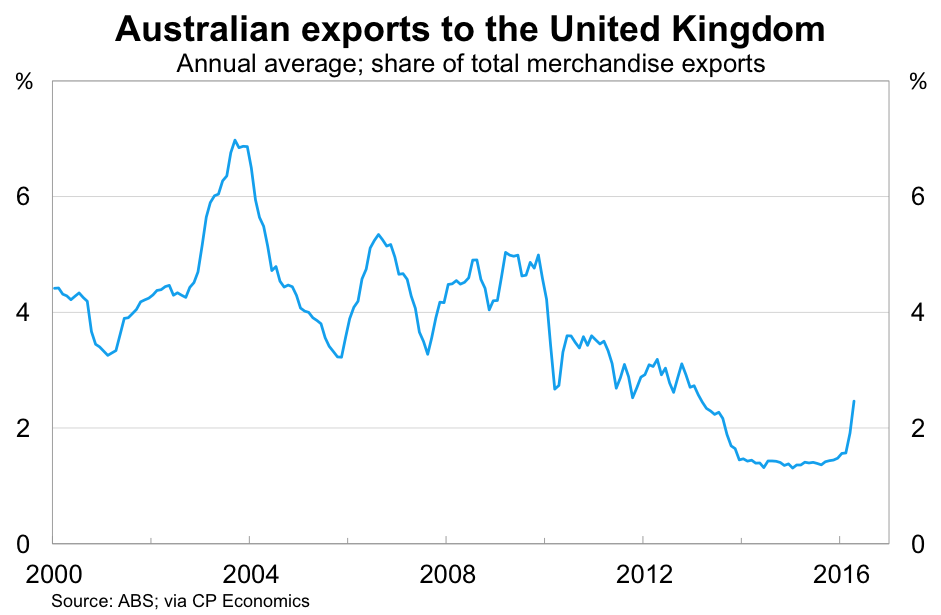

The good news for Australia, whether the result is “remain” or “leave”, is that the United Kingdom is no longer a major destination for Australian exports. Over the past year, the UK has been the destination for around 2.5 per cent of Australian exports. Even then that number is being held up by temporary gold exports that have taken place over the past two months.

In other words, Australia is well placed to manage a storm in the UK. The main problem is when it spills over to the euro area, most notably Germany, and puts downward pressure on global growth. Most analysts believe that a Brexit will be damaging to the euro area, particularly to its biggest exporter Germany, but there remains a great deal of uncertainty.

Australia has already experienced market volatility originating from concerns over a Brexit and that would obviously be amplified in the event that the “Leave” campaign proves victorious. The most notably effect though will come via a stronger Australian dollar and a “flight to quality” as fund managers and investors seek refuge in higher quality assets (which these days includes the Australian dollar and federal government debt).

This could trigger an immediate response from the Reserve Bank of Australia. They may not have an explicit easing bias, but the market still expects the bank to cut rates again by the end of the year. A sharp increase to the Australian dollar, combined with expectations that the Federal Reserve will delay further rate hikes, could prove sufficient for the RBA to cut rates at either the July or August meeting.

Australian labour market

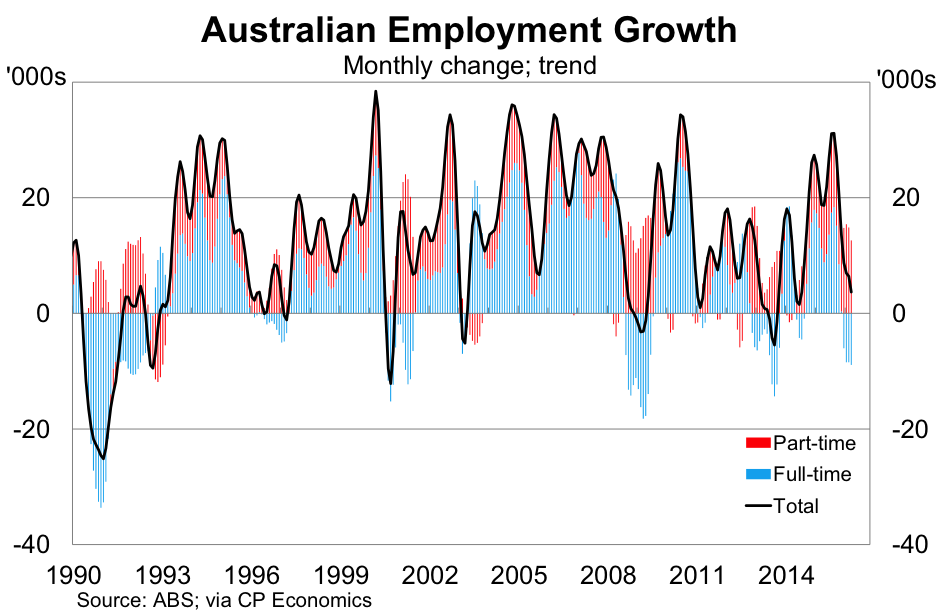

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released their monthly Labour Force Survey last Thursday and it was a mixed affair for the Australian economy. Employment growth across the country has slowed significantly since October last year. The economy created 3,700 jobs in May, its lowest level since September 2014, and well below the 31,100 posted in October last year.

The main concern though for the Australian economy and investors is our inability to create high quality full-time jobs. Full-time employment fell by 8,900 people in May and this reflects a broader casualization of the Australian labour force. We are employing more people but those jobs aren't necessarily high-paying high-productivity roles.

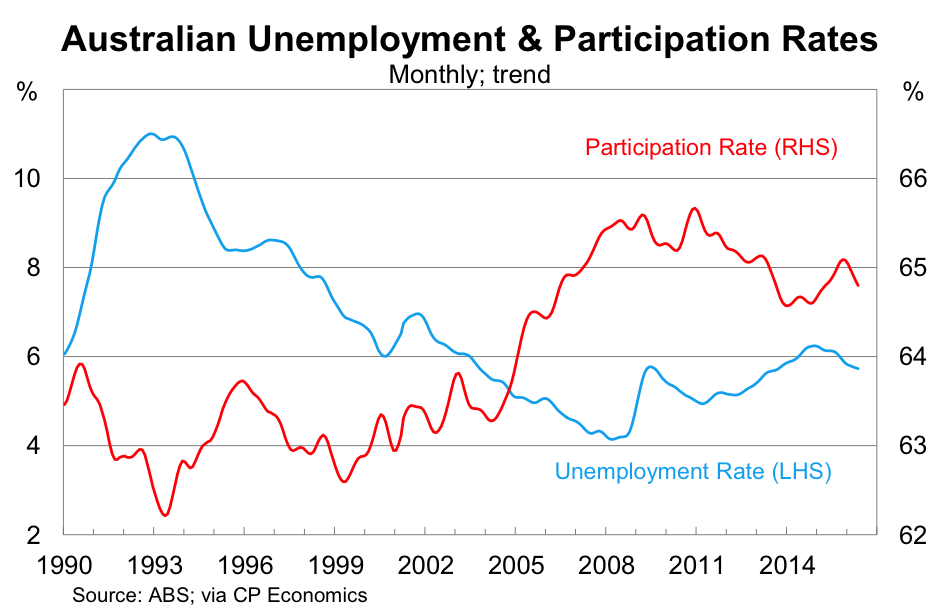

The unemployment rate remained at 5.7 per cent in May and the participation rate eased slightly to 64.8 per cent. The first figure remains pretty good, particularly given the decline in national income that has taken place over the past three years, the latter though is a weak number.

A lower participation rate indicates that Australia is relying on a smaller group of people to produce its goods and services. This is actually a phenomenon that has occurred over a number of years and to a significant degree reflects the fact that baby boomers are beginning to enter retirement.

The implications for investors, though, are profound. Softer participation suggests that Australian companies will need to place a greater emphasis on productivity growth in order to replicate past growth performance. No longer can Australian companies simply rely on population growth and strong national income growth to drive earnings and valuations.

Some readers might notice that I have chosen to focus on the trend figures rather than the more volatile seasonally-adjusted figures. Some readers might also notice that markets tend to trade and fluctuate on those more volatile figures. Short-term gains might be made based on the volatile seasonally-adjusted figures but the trend figures are a much better indicator of the Australian economy.

It's worth keeping that in mind when you see the market react strongly to the monthly data. In this case the monthly seasonally-adjusted numbers overstated the strength in the Australian labour market. Don't be surprised if this is offset in later months via weaker than anticipated employment growth.

China's economic transition

Finally, I wanted to touch upon an excellent speech on China made by Reserve Bank assistant governor Dr Chris Kent in Brisbane last Thursday. It's well worth a read if you are so inclined.

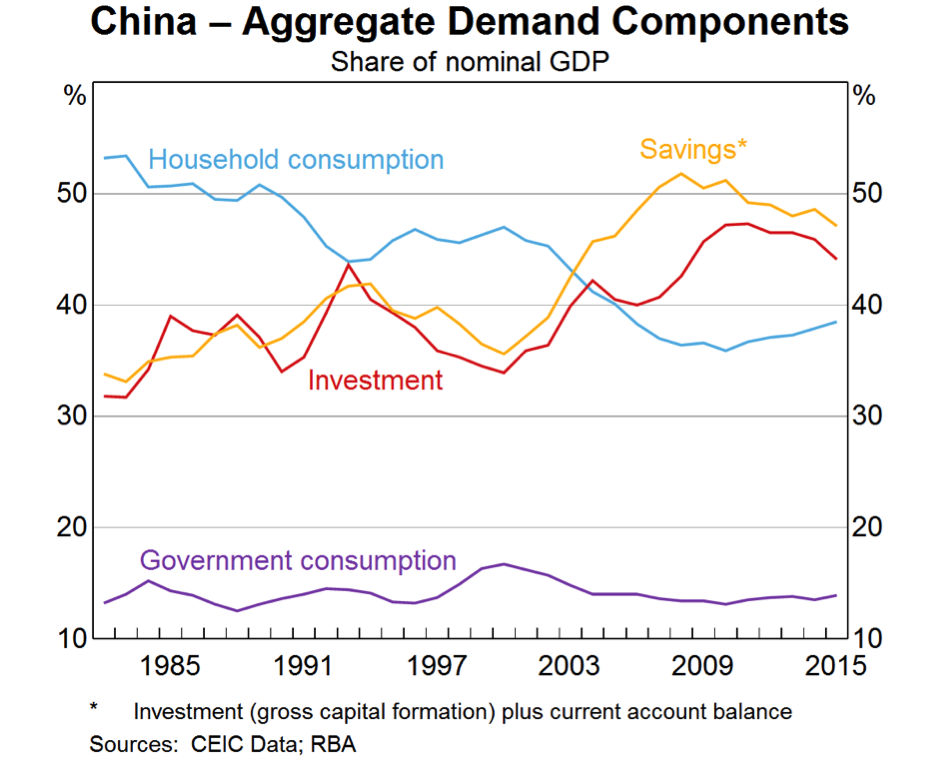

China are in the midst of an economic transition that is largely unprecedented in size and scope. Chinese authorities are hopeful that this transition, from infrastructure and residential investment towards household consumption, takes place with minimal disruption. History suggests that this is unlikely.

This transition has created a difficult balancing act for Chinese authorities between, according to Kent, “the goals of shoring-up short-term growth and pursuing institutional reforms that would help to sustain growth over the longer term and assist with the rebalancing of demand from investment to consumption.”

“China will continue to provide Australia with significant economic opportunities over the longer term, including in sectors such as agriculture, education, tourism and a wide range of business services,” Kent said. “Along the way though, we should be alert to the risk of adverse developments that could lead to a sharp economic slowdown in China.”

Chinese investment has been a boon for the Australian economy. It drove the increase in commodity prices that boosted Australian incomes throughout the 2000s. The past few years though have been a very different story, with investment declining as a share of the Chinese economy, putting downward pressure on iron ore and coal prices.

House prices and residential construction remain a key risk for the Chinese economy. One reason is that China's working age population is set to fall significantly over the next decade. This will put downward pressure on housing demand, leading to weaker growth in residential construction and softer house prices.

“The slowdown in residential property investment over the past few years has affected heavy industries that produce construction materials, including steel,” Kent said. “The weakness in demand of late, combined with earlier strength of investment, has led to a rise in excess capacity in a range of manufacturing and mining industries, and widespread deflation in industrial prices.”

In other words, softness in residential property investment is a leading cause of lower steel prices, which has flowed through to lower commodity prices for key Australian miners. This is a process that is expected to continue, in one form or another, over the next decade.

From the perspective of Australian investors, it would be wise to focus greater attention on those sectors that are likely to see stronger Chinese demand. Greater exposure to education, tourism and business services could prove lucrative; it may also be wise to minimise exposure to those firms relying on Chinese infrastructure and residential investment. This includes big Australian miners such as BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto.

With regards to China's rebalancing, Kent notes that “Chinese consumption growth is already very strong and, historically, it has been rare for economies to experience stable and strong consumption growth during such a rebalancing.” Investors should prepare themselves for not just a slowdown in Chinese investment but also Chinese consumption and that could lead to softer than expected real GDP growth.

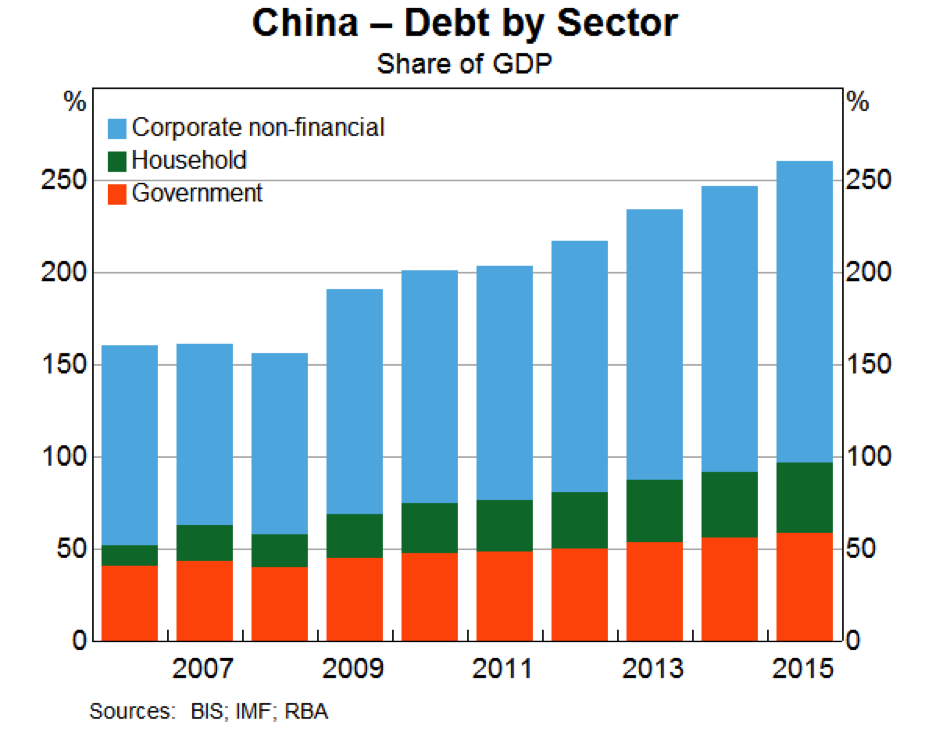

Perhaps the greatest risk to China's economic transition is their rapid accumulation of corporate and household debt. China's debt level remains below many advanced economies but the rapid accumulation of debt suggests that China will make up ground quickly. Although there are no outward signs of distress in the bank system, the fact that Chinese growth is relying so heavily on debt is a cause for concern.

It is worth noting that Chinese debt, much like Japanese debt, is largely financed by domestic currency. A considerable proportion of Chinese debt has arisen from state-owned financial institutions lending to state-owned or controlled corporations. This largely negates the risk of default. Nevertheless, investors should keep an eye on any news related to Chinese debt accumulation. The moment that Chinese authorities try to slow down credit growth is the moment that Chinese economic growth comes under the greatest pressure.