The dividend dilemma

Summary: Considering Australia's high dividend payout ratios and soft business investment, it looks like something will have to give in the long term - strong dividends cannot survive in an environment where profits are under pressure and wage growth has slowed. |

Key take out: Many Australian companies seem to be operating as though they are in the last decade - but one thing I think for sure is that the current strong dividends are not sustainable. |

Key beneficiaries. General investors. Category: Economy. |

Australian dividends

Soft company income and profits, combined with historically high dividend ratios, continue to squeeze business investment. If the situation isn't addressed soon it could undermine the long-term performance of Australian companies and economic growth.

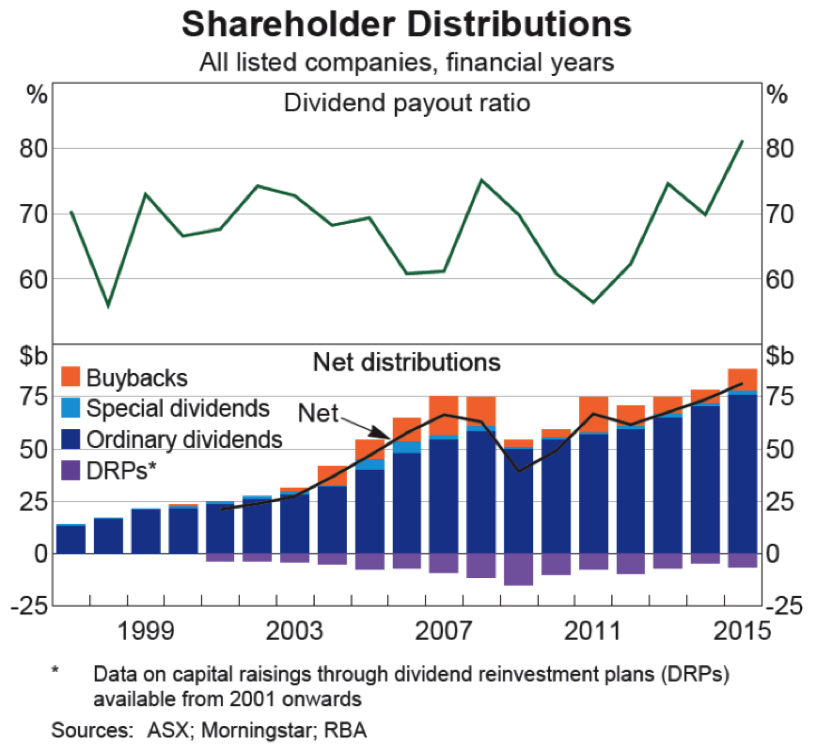

According to recent research by the Reserve Bank of Australia, the local market's dividend payout ratio is remarkably high by international standards. Over the period from 2005 to 2015, Australia averaged a dividend payout ratio of 67 per cent. This compares to 60 per cent in the United Kingdom; 55 per cent in Europe and 48 per cent in the United States.

The main reason for this appears to be the usage of dividend imputation as part of our tax system. Owners of Australian shares certainly don't mind. For the past decade, strong dividend growth has helped to offset some of the weakness in the ASX 200.

But maybe investors should mind.

Is it possible, for example, that high dividend payouts have undermined future investment and company performance? The OECD certainly believes so.

“Weak business investment globally may reflect increased pressure on companies from activist investors favouring the short-term benefit of shareholder distributions over longer-term investments,” the OECD have commented.

Australia's situation is somewhat unique when compared with other markets. Few advanced economies have experienced such a persistent “income recession” as Australia has over the past three to four years.

As a result, the recent surge in the dividend payout ratio has occurred in a lower earnings and profit environment. In other words, Australian companies are reluctant to cut their dividend policies. That leaves precious little spare cash for other purposes – namely expansion and investment.

This reluctance can create some amusing situations. According to the RBA, “the major banks [paid] out around $23 billion in dividends in 2014/15, an increase on the previous year, while also choosing to raise around $23 billion in equity in 2015.” It's all very circular; giving money to investors with one hand and then trying to get it back with the other.

Then there's some less amusing situations: Namely, the ongoing decline in non-mining investment even as interest rates hover near historically low levels.

Nevertheless, it's understandable why investors have such a strong preference for dividends. Australian households became more cautious in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Income in my pocket is certainly safer than uncertain business investment.

We may have also seen a shift in demand for income over capital gains. That makes a lot of sense given income growth from traditional sources (i.e. wages and salaries) have been so weak.

This has been amplified by Australia's ageing population and the concentration of wealth among “baby boomers”. Retirees are often asset-rich but cash-poor and stocks that pay high dividends have obvious appeal. Dividends are particularly appealing right now given it is almost impossible to earn a decent return on deposits and rental growth is at its lowest level in decades.

So basically businesses are foregoing productive investment in order to keep shareholders happy. However, rather than investing in new productive assets, households are using dividends to support their existing lifestyle, or leveraging this income to splurge on housing.

Australian businesses are their own worst enemy. Evidence suggests that the “hurdle rates” for new investment tend to be excessively high for many companies. Australian business leaders are often seeking returns that simply aren't reasonable in a low interest rate environment.

It's no longer 2005 – but many business leaders haven't realised that yet. In the process they are putting off productive investment and draining their companies of cash via strong dividend growth. It strikes me as short-term thinking and a philosophy that ultimately isn't in the best interests of domestic investors or the Australian economy.

What I can say with some certainty is that this situation isn't sustainable. If earnings and profitability don't pick-up soon, something needs to give. Investors should prepare themselves for either lower dividends or a freeze on existing dividends.

That won't be viewed positively, by either investors or the media, but starving businesses of capital during difficult times is rarely a recipe for long-term economic success. If lower dividends translate into stronger business investment and expansion, then investors could ultimately become the big winners.

Federal Reserve meeting

The Federal Reserve is meeting on Wednesday and Thursday this week. They won't be lifting interest rates this month but the meeting has important implications not just for the US economy but also for Australia.

For all the talk about rate hikes, the argument in favour remains somewhat flimsy. It is tougher to justify a rate hike now than it was at the Fed's last meeting in April.

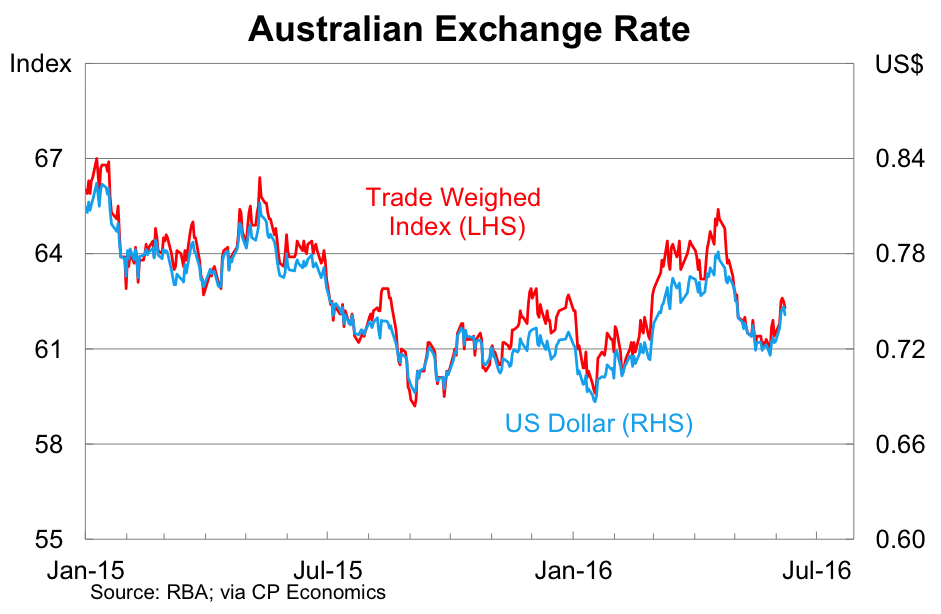

That's hardly ideal for the Australian economy given our desperate need to lower the Australian dollar. A weaker dollar helps to offset softer commodity prices and also supports Australia's non-mining sector, improving the competitiveness of Australian businesses.

The dollar dropped to as low as US71.6c on May 30 but has since increased by 3.6 per cent against the US dollar following a series of poor US economic data that has pushed back expectations of a US rate hike.

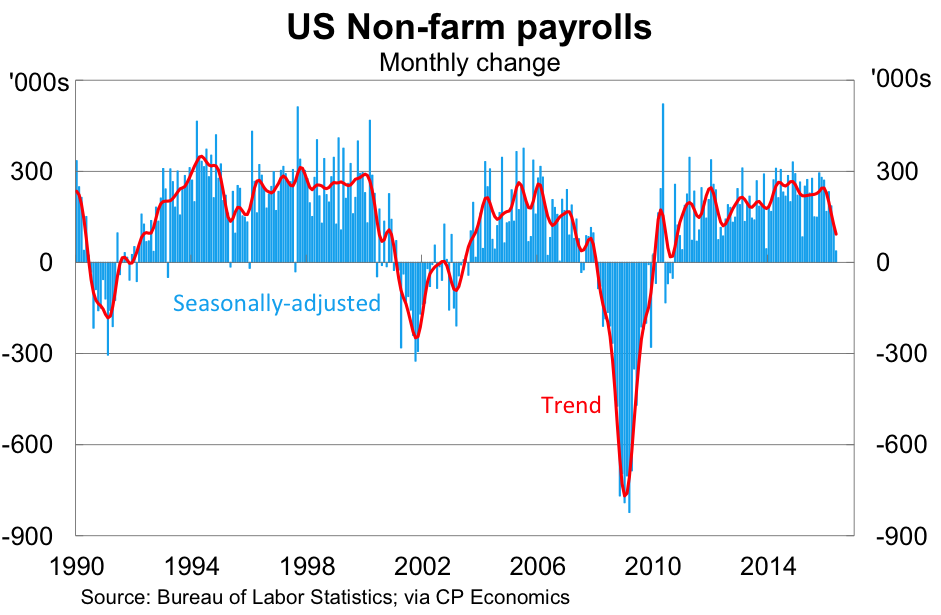

The most concerning was the employment data. The data for non-farm payrolls, released in early June, was nothing short of dreadful in May. Non-farm payrolls is now rising at its slowest pace since October 2010.

Another issue for the Fed is that the core PCE deflator, the bank's preferred measure of inflation, remained at 1.6 per cent in April and is still well below the Fed's annual target of two per cent. Perhaps more troubling is that inflation expectations are now at the lowest level in over a quarter century.

In other words, it will be difficult for the Federal Reserve to justify a rate hike this year unless the data on employment and inflation improves significantly. Hiking into a slowdown would prove disastrous.

Fed chairwoman Janet Yellen has remained upbeat in her recent comments on the US economy, but increasingly it is difficult to understand why. The Fed needs to change its language, acknowledging softer inflation expectations and the loss of momentum in the labour market, and markets should be ready for it.

The most likely scenario is that the Australian dollar spikes in the aftermath of Thursday's Fed meeting. Delaying a rate hike until 2017, which I anticipate is how markets will view the Fed's statement, will put a rocket under the Australian dollar. It's quite likely that the Australian dollar will return to the US75c to US76c range before the week is over. Maybe even higher.

That's hardly ideal for our economic transition, which is so heavily anchored to a weak Australian dollar. But investors should be salivating at the prospect that the Reserve Bank of Australia will respond with another rate cut or a series of rate cuts. They cannot afford a high Australian dollar and investors stand to gain as the bank tries to push it towards the US70c level.

The challenge for investors is separating the short-term benefits from the long-term implications. A strong US economy is good for global growth and financial markets. It's the engine that drives the global economy. The long-term implications of the Federal Reserve delaying policy normalisation is decidedly negative.

But in the short term, markets will jump on the realisation that interest rates will be lower for longer. There is even the possibility that the next move for the Federal Reserve is down rather than up (and that implies another round of quantitative easing). For the short-term speculative investor, sometimes bad news is actually good news.