The correction: Was it leverage?

Summary: Margin loans outstanding are very low so there was no build up prior to the correction. Little of the available credit is being used, which is a sign that leverage has played no part in the current correction. Volatility could be a key reason why leverage is so low – investors aren't prepared to borrow into this market. |

Key take-out: We can make a broader observation on the economy – by and large, growth to date is not being driven by credit at all. This is good news as it suggests the economy is on a more stable footing. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Shares. |

At its lowest point to date the Australian market was down nearly 18 per cent peak-to-trough from its high in April, although some of the big blue chips like the banks lost about 25 per cent.

These are huge moves driven as we know by a combination of factors, from regulatory action against the banks, to anxiety over China and global growth more broadly.

For investors, a key issue is the extent to which leverage may have driven the current rout. The reason this is important is because it cuts to the heart of market stability. So for instance if our market has been propped up by leverage, then it's more exposed to the types of corrections we've just seen – it can make them worse than they would otherwise have been.

The way it can work is that leverage, typified by margin lending, can magnify any negative sentiment in the market as margin calls (a demand from a broker that clients deposit more cash to cover potential losses) are issued. Depending on the extent of the margin call, investors often just opt to just sell their shares. They do this to lower the capital they are required to front up with. That then exacerbates the selling pressure.

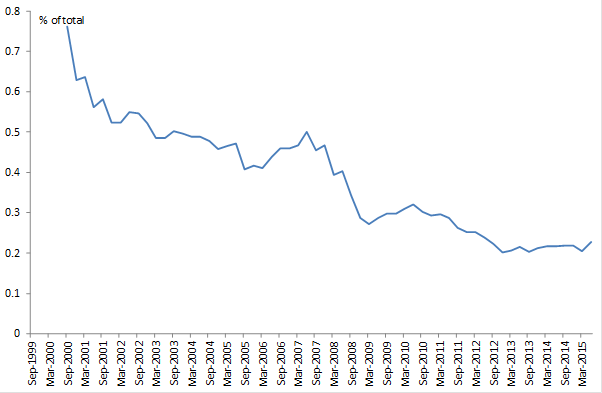

One of the key problems we've got in analysing this issue is that the data isn't all that timely. The latest figures only take us to July and so they actually miss the recent rout. Having said that, when you take a look at chart 1 (as dated as the data is) we can still take a pretty good guess and get a sense as to the role leverage played in this rout.

At the outset, it looks like leverage – at least leverage represented by margin loans – played only a very small role.

Chart 1: Total margin lending outstanding

Source: RBA

As you can see, margin loans outstanding are actually very low – so there was no build up prior to the correction. At around $12.4 billion, total margin loans outstanding are well below the pre-GFC average of $22bn and about 70 per cent below the 2007 peak. That's despite the average margin lending rate currently being about 2.25 per cent below what you could get in 2007.

What's even more interesting is that the downtrend has continued as the domestic and global economies have continued to recover. As confidence has picked up. In 2012 for instance, the average amount of leverage was $17bn.

When you're talking about a market with a total capitalisation of $1.45 trillion, $12bn is not a lot – less than 1 per cent of the market. Let's say for argument's sake that this current correction saw another drop off in margin lending. That's what you'd normally see as margin calls were issued. Even if we assume the kind of falls in leverage outstanding that we witnessed through the European debt crisis – average quarterly falls of 7 per cent – that still only equates to about $200 million per month during this current rout. The thing is, that's a fairly meaningless figure. In terms of the value of shares traded, just one of the banks did more than that in one day of trading last week.

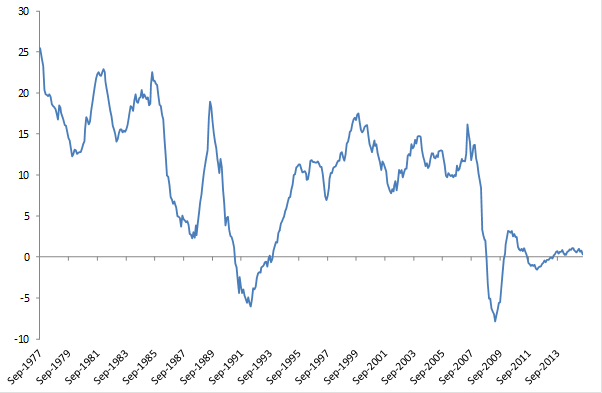

The numbers are even lower when you take into account the total funds – or credit - available to margin account holders. Admittedly, and apart from a brief period from 2005 to 2008, the trend has been down anyway. Yet as it stands, we're just off a record low, with account holders drawing down only about 23 per cent of the funds available to them.

That so little of the available credit is actually being utilised is another strong sign that leverage really has played no part in the current correction. Or thought of another way, in its post-GFC performance.

What about other forms of leverage you might ask? The activities of hedge funds for example. It's hard to know exactly as data is limited, but we can infer that their role is quite small. According to ASIC, Australian hedge funds have less than $100bn under management. A fraction of the $1.6trn in the equity market. Indeed 70 per cent of the total market capitalisation is held by domestic real money managers – which are not leveraged. Superannuation funds dominate. Global real money managers would make up a significant proportion of the rest. That doesn't leave much for foreign hedge funds to move the broader index on leverage derivative plays. Individual stocks perhaps on some momentum play but less likely the entire market.

Chart 2: Margin lending outstanding as a proportion of credit limit

Source: RBA

This is all very consistent with a broader observation that we can make on the economy. By and large, growth to date is not being driven by credit at all. Total credit growth remains well below average – up only 6 per cent for the year compared to the average of about 11 per cent. Personal credit growth is even lower, up a mere 0.4 per cent for the year compared to the usual rise of 9 per cent. So for all the woe and despair about the Australian economy, leverage has had little to do with economic growth to date. Not just for the market, but the entire economy. A rebound in lending to business and property is it. Not that this is a bad thing.

Chart 3: Personal lending growth

Source: RBA

This is good news by the way as it suggests the economy we have to date is on a much more stable footing.

Why is leverage so low? Volatility could be a key part of it. Households have shown that they will get into to debt where they see a good reason – property for instance. But the sheer volatility on the equity market, the fact that foreign investors have yet to get on board and the simple threat of having to crystallise a loss all weigh against the decision to gear. Investors aren't prepared to borrow into this market. Fair enough too.

Not that they necessarily do even in the best of times either. So we shouldn't get carried away by any negative implications this data might carry. Consider that even at the peak, the height of optimism, leveraged accounts were only about 2.8 per cent, or thereabouts, of the market. Not huge at all.