SPECIAL REPORT: The beginning of the end for geoblocking?

Australia: the lucky country, a proud island nation and… the pirate capital of the planet.

We may not be pillaging every ship that hits our shores, but when it comes to TV shows and movies, Australians will to do whatever it takes to access quality video content.

This point has been proven time and time again. Piracy and copyright specialist news site, TorrentFreak frequently runs data on TV shows that are being pirated across the internet, and within the past couple of years, Australia has consistently ranked as one of the top countries engaging in this activity. And if that’s not enough evidence of our piracy ways, earlier this year US Ambassador Jeffrey Bleich was forced to plead with Australians to stop illegally downloading Game Of Thrones.

There’s no doubt that the mass adoption of BitTorrent and other online sharing tool revolutionised the way in which many Australians enjoy some of the best content on the web, and in turn posed a significant threat to the whole media supply chain. Now, we're sitting on the cusp of another transition; the mass adoption of a new set of geeky tech tools that have the potential to once again turn the content industry on its head.

The age of VPNs

These tools are VPN and proxy services.

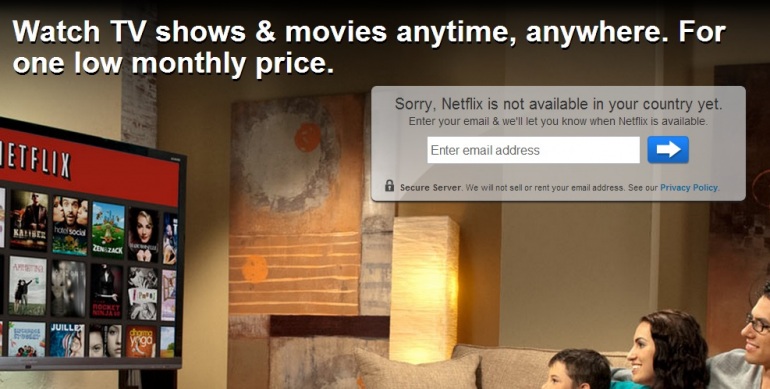

Once upon a time, they were primarily used to cover a company or a user's tracks on the internet. Now, the rise of content geo-blocking has given them a new lease at life - they’ve become a gateway to access forbidden overseas services like Netflix and BBC iView from Australia. We're locked out of these sites because of the licensing system implemented by the TV and movie studios. They charge services like Netflix based on where they want to distribute their content and if sites like Netflix don't block overseas users, then they would be in breach of contract.

As for getting around this, consumers can use free services, or pay as little as $5 per month, to use a VPN or proxy to trick these companies into thinking that they are accessing their system from US or the UK.

The growth of VPNs and other services is quite simply a matter of economics, where the public is willing to do whatever it takes to bypass barriers and get what they want quickly and at the best possible price.

Overseas companies like Netflix offer more content for less than half the cost of most of their Australian counterparts. Even with $US5 ($A5.43) per month subscription to a VPN and proxy service and a $US7.99 ($A8.76) monthly subscription to Netflix is slightly cheaper ($A14.19) and features more TV shows and movies than the $A14.99 per month service offered by an Australian equivalent, QuickFlix.

Seems like a simple case of dollars and cents, but QuickFlix’s CEO Stephen Langford begs to differ. He says that with his service you gain access to content to popular exclusive content - like HBO TV shows - that’s not on Netflix. He also contends that QuickFlix also contains a DVD mailout service and can easily stream content across multiple devices and players making it more accessible and easier to use than its overseas counterparts.

Langford also maintains that his company and the roughly $2 billion video entertainment market in Australia and New Zealand shouldn't be threatened by VPNs or proxies. Nor should it be worried by piracy, he says.

“I don’t see it as mainstream behaviour. I also don’t see it as completely satisfying the entertainment requirements of mainstream consumers... we don’t see it as an issue,” Langford says.

“VPNing or backdooring is a fringe behaviour. I suspect that if we had a look at the sorts of folks using VPNs, I think there would be a reasonable cross-over with those who use BitTorrent,” he said.

Fringe behaviour no more

But according to the companies operating these anti-geoblocking services, Australia is far from a “fringe” market. Business is booming.

“Australians are among the top 5 of our user base,” lead developer of anti-geoblocking service UnoTelly, Nicholas Lin told Business Spectator.

“They make up about 10 per cent of our customers. While 10 per cent does not seem significant by itself but it is a large percentage since we are a global company with customers from almost every single continent,” Lin said.

“Without any focused marketing effort on the Australian market, our Australian user base has almost tripled compared to last year relying solely on words-of-mouth.”

John Fogerty, the owner of free anti-geoblocking service Tunlr mirrors Lin’s sentiment.

Tunlr operates differently to UnoTelly in that it limits the amount of Australian subscribers that can access US Netflix at one time due to resource constraints. There may be a queue to access the service, but that hasn’t quelled the demand for it.

“Demand for Australian slots on Tunlr's Netflix whitelist is much higher than availability. Currently, Australia ranks number 2 after Canada [for demanding Netflix],” Fogerty said.

Fogerty’s comments failed to sway Langford’s opinion on the issue. But the stories did prompt Internode founder Simon Hackett to reassess the impact of VPN services.

When originally asked about the rise of the use of anti-geoblocking services in Australia, Hackett said that the systems were still relegated to the realm of “the geeks who understand it”.

However, the weight of evidence is mounting and Hackett admits that the transition from fringe behaviour to mainstream acceptance can happen in a blink of an eye.

“I’ve seen this before,” Hackett said.

What Hackett is alluding to is the enormous capacity for self-education on the internet. Using torrents was once seen as fringe behaviour but it didn't take long for the content industry to wake up and take notice. The same can be said for the adoption of anti-geoblocking services and Hackett adds that while the signs of growth may seem muted, it will be “exponential” from here on out.

But is it legal?

One point holding back the rapid adoption of anti-geoblocking services may be the confusion as to whether or not using these services are legal. Unlike piracy, which is known to be illegal, anti-geoblocking tools sit in a grey area of the law. So far, the most authoritative Australian comment on the matter was made in 2011 by a spokesman to the then Attorney-General Robert McClelland.

"In relation to the use of VPNs by Australians to access services such as Hulu and Netflix, on the limited information provided there does not appear to be an infringement of copyright law in Australia," the spokesman told The Australian.

"Whether the Australian users have committed an offence by deceiving these providers about their identity, or eligibility to receive their services, would depend on state or territory criminal law."

Though, the subject is still open to debate. Providing Business Spectator with a detailed legal analysis on the topic, Dr Nicolas Suzor, from QUT School of Law and the ARC centre of excellence for creative industries and innovation, says that as the law stands it is “conceivable but not likely than an Australian users could be sued” for using these services .

So, if an Australian user was to be sued, the case would revolve around three points.

Firstly, the user needs to lie about their home address to gain access to the service, and that would breach Netflix’s - or any other content provider’s - terms of use. While this may not result in a lawsuit the user may be disconnected and lose any kind of prepaid balance they’ve allocated to the service.

Secondly, if an Australian is openly discovered to be using this service, the content creator - the movie and TV studios producing the shows - may sue the content provider who in turn, may pass the damages onto the Australian user.

Finally, the content provider may be able to mount a criminal case as a result of the Australian user providing a fake address to access the service, though US courts are yet to find this as a sufficient enough reason to trigger a criminal suit. Criminal cases in regards to copyright infringement are also a possibility, although as Suzor points out, only if they are of a “commercial scale” - a term not well defined in Australian law.

Giving the public what they want

All of these laws and theories are yet to be tested in the courts. Having said that, Suzor contends that they need not be tested at all if the content industry broke down this idea of geoblocking and licensed content on an international scale rather than on a region by region basis.

“Clearly, Australians want to do the right thing and pay for access to content, but are prevented from doing so by the lack of viable distribution channels in Australia,” Suzor says.

“Copyright infringement is a symptom of market failure here; addressing the unmet demand would be likely to have dramatic benefits for copyright owners.”

Internode’s Hackett agrees. He says that Hollywood’s licensing methods are at the root of the problem, whether it's piracy or the use of VPN and proxies.

He is also adamant that the content industry's attempts to turn the telco sector into their “unpaid policemen” is a short-sighted and flawed approach.

“Telcos shouldn’t have to solve broken business models,” Hackett says.

Breaking the blockade

The Australian Media and Communications Authority and the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission both told Business Spectator that they are keeping an eye on the issue.

However, judging by their statements, both watchdogs appear to be leaning towards the idea of acting against the current geoblocking regime rather than supporting or enforcing it. The Greens are also pushing forward legislation that aims tackle the issue through the amending the Copyright Act. There’s also a possibility that this issue could be raised in the findings of the ongoing IT price inquiry.

Of course, the industry could pre-empt these moves and attempt to breakdown their own blockades and eliminate the anti-geoblocking services market altogether. However, this is easier said than done. For now, the industry is clinging to the current revenue regime. And that’s fair enough when you consider Jeffrey Bleich’s point that it costs almost $6 million to produce an episode of Game Of Thrones.

There's also long running speculation that the US major players like Netflix and Hulu launch in Australia, but unless they break into the country with content line-up and price points they have in the US, its likely that Australians will still opt for the US version of these services. Netflix has launched in Canada, yet the country still leads the world in breaking into the US version of the system, simply because the Canadian off-shoot offers less content than its US counterpart.

While there are many factors in play the adoption of anti-geoblocking services is on a similar tangent to that of torrents and that poses a substantial challenge to the content industry. The age of VPNs is nigh and it could well be the beginning of the end for geoblocking.

Dr Nicolas Suzor's full evaluation of the legality of anti-geoblocking services as well as other emailed statement relating to this story can be found here.