Special Report - A Financial Maze: Navigating Australia's Aged Care System

Contents

The aged care labyrinth

It’s a well-known fact that Australia, like most other developed nations, has an ageing population. This is putting unparalleled pressure on our systems, infrastructure, but above all, our people who depend on these.

Aged care is tricky to navigate at the best of times, let alone when you’re desperately in need and lacking means. There is a minefield of information out there, with the forever changing costs often buried in the fine print. Overseen by a handful of government departments, there are many fingers in the pie, setting up the aged care system as somewhat of a decentralised labyrinth.

Our job at InvestSMART is to simplify your financial journey. But we are very conscious that one size doesn’t fit all, especially with matters like this.

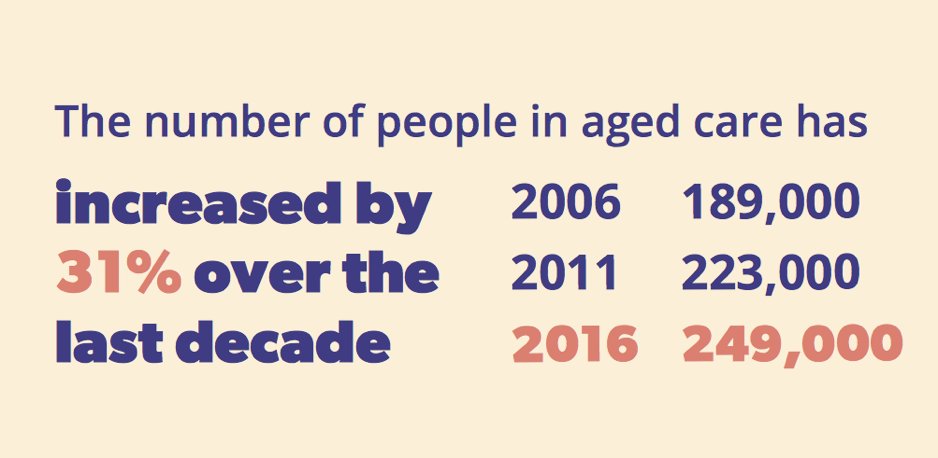

The last big aged care reforms were announced in 2015, coming into effect incrementally since. But it was staggering statistics that compelled us to compile this special report.

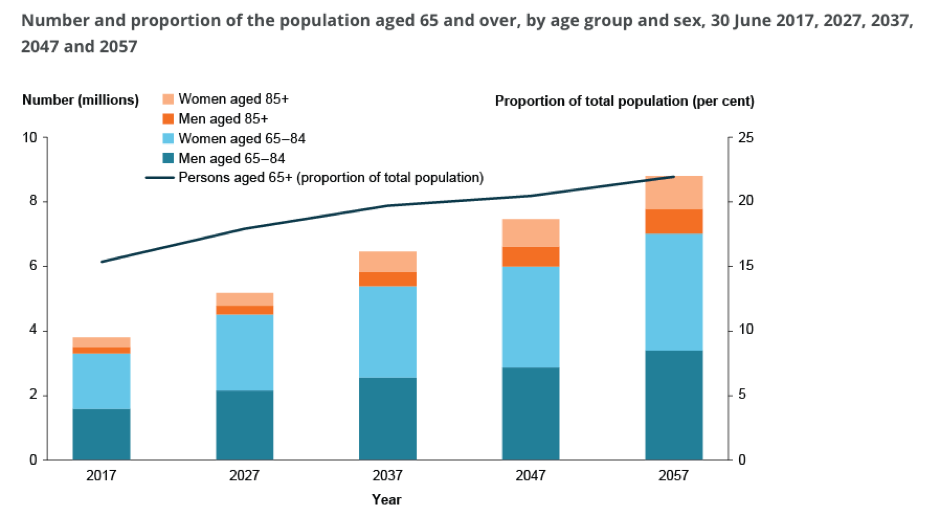

The size of the 70-plus cohort in Australia will increase by one million people over the next two decades. On top of that, the Aged Care Financing Authority (ACFA) claim the number of people aged 80 and older will more than double by 2037, from just under 500,000 people in 2017 to more than one million.

Quite simply, most Australians aren’t prepared financially to get older. The costs are high, and the subsidies often low. The family home looms large in aged care discussions, being the biggest asset an individual typically owns.

There is a slew of things to think through. In addition to aged care costs, it’s important to undertake careful estate planning to ease tax burdens for loved ones when you pass. This is otherwise known as the super ‘death tax’ – and it can become quite the cost for non-dependents you leave behind. Keeping a current will is important too, for anyone of any age, or else your assets will be divvied up according to intestacy laws, which can vary greatly across jurisdictions.

On that note of state-by-state variance, the rules outlined in this special report only apply to retirement villages covered by the Commonwealth, not independent living villages governed by state legislation.

A rule of thumb; start preparing for aged care a decade before you plan to take the first steps. And preparations might be brought forward to your mid-life if you’re factoring in parents.

Reality is, the evidence shows Australians don’t even start to think about their retirement until they turn 50. In the scheme of things, there’s little time in between that first thought and big move.

We hope you find this special report useful.

An ageing Australia

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. GEN. Canberra: AIHW.

| Australian's projected life expectancy (years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2025 | 2035 | 2045 | 2055 | |

| Life expectancy at birth Men Women |

91.5 92.6 |

92.6 94.5 |

93.6 95.3 |

94.4 96.0 |

95.2 96.6 |

| Further life expectancy at age 60 Men Women |

26.4 29.1 |

27.9 30.3 |

29.3 31.5 |

30.5 32.4 |

31.5 33.3 |

| Further life expectancy at age 70 Men Women |

16.9 19.3 |

18.2 20.4 |

19.3 21.4 |

20.4 22.3 |

21.3 23.1 |

| Note: Cohort life expectancy at a given age takes into account known or projected changes in mortality over the remainder of the person's lifetime. Source: Treasury projections. |

|||||

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. GEN. Canberra: AIHW.

The real cost of care

By the end of the decade, Australian demographer and futurist Bernard Salt believes the ‘R’ word will be dropped and retirement villages will be reclassified as lifestyle villages. But visiting some of these villages in 2018 gives the impression this could still be a long way off.

You may find you’re paying as much for standard aged care accommodation as you would a nice hotel.

It’s important to consider a range of facilities that could be appropriate for individual needs, have meetings with those who make the shortlist, and discuss fees early in the consultation process. Most people wouldn’t buy a house without undertaking proper due diligence – meeting the agent, getting a feel for the surrounding area, and looking for hidden costs that might escape the headline sales figure. This is no different.

On top of the lump sum deposit required to enter aged care, there are ongoing fees. Many aged care facilities will also charge a premium for the full bells and whistles, which can include things like hairdressing, cable television and special fitness programs.

Fees explained

Before signing up to an aged care provider, it’s important to understand exactly what the outgoings are. Costs should be limited to the following:

- A basic daily care fee that will be paid by all people who receive residential care.

- A means-tested care fee that is an extra contribution to the cost of care and based on the resident’s income and assets.

- A daily accommodation payment that is also dependent on a person or couple’s assets, which is paid either as a lump sum refundable deposit, a daily accommodation payment, or a combination of both.

- Fees for extra or additional services such as a room with a view, meal choice or cable television that are in addition to basic services provided.

On top of that, most financial advisers recommend individuals budget an extra $100-150 a week for activities on top of that, like coffees and catch-ups.

Referring to the above list, everyone in the aged care system must pay a basic daily care fee, which may be paid regularly or annually, as well as a means-tested care fee.

The basic daily care fee is set by the Australian Government and currently amounts to $50.16 per day for residential care and $10.32 for home care. The fee is calculated as 85 per cent of the single person rate for the basic age pension. The basic daily fee is indexed every six months with the age pension, in March and September. These figures are correct from March 20, 2018 and apply to those who first entered care from July 1, 2014.

It’s a different situation for those who entered care before July 1, 2014. Right now, these residents will pay less than $50.16, on average, unless they fall under the Non-Standard Resident Contribution rate where they could then be charged up to $56.94 at current rates.

There is somewhat of a saving grace, because caps are placed on the means-tested care fees. As it stands now, an individual can only be asked to pay a maximum annual amount of $26,964.71 in care fees in the aged care system, and will come up against a maximum lifetime amount of $64,715.36. That’s the ceiling as it currently stands. However, maximum limits do increase every six months, in line with the basic age pension. There aren’t any caps on fees for additional services. But watch your step. It has been said that often ‘a room with a view’ will be a hidden cost that falls under additional service fees.

Asset and means

Some individuals in aged care will be exempt from paying means-tested care fees because of the income and assets tests. The Department of Human Services calculates the rates under both tests for every individual and, somewhat generously, the test that results in the lowest rate will apply.

As of March 20, 2018, the highest level of income you can earn and still fall under the ‘income-free’ zone is $26,660.40 for a single person, $26,192.40 for a couple separated by illness, and $20,703.80 for a couple living together in home care.

All these figures are indexed in line with the age pension, however Federal Government changes to the means test and the taper rate in 2017 have made it more difficult for some to qualify for payments.

The asset-free threshold currently stands at $48,500. Up until that point, the government covers means-tested care fees and daily accommodation payments. That asset-free threshold is determined by the Department of Social Services without much of a rationale. Assets limits are updated every January, March, July and September.

After the asset-free threshold of $48,500, individuals must pay fees of around $50 per day. Then there is a first asset threshold of $165,271.20. This applies for accommodation fees. If you have assets over that mark, your accommodation isn’t subsidised at all, and you will need to shop around for better rates. The second asset threshold is $398,813.60, with fees increasing again above this mark too.

Louise Biti, director at Aged Care Steps, notes there will be exceptions to the $165,271.20 asset-free threshold (current at March 20, 2018).

“In some cases, you will have assets below that threshold but really high levels of income from things like government pensions, defined benefit pensions, or distributions from family trusts,” explains Biti.

“You may not get the government subsidy because of these income streams – the formula always takes into consideration both income and assets.”

For clarification on what’s considered an asset (everything from cryptocurrencies to collections), check out the Department of Human Services. As well, it’s very important to heed the different thresholds for aged care and pension tests. For reference, the tables below detail the income and asset tests pertinent to the pension only.

| Centrelink income test limits for pensions from March 20, 2018 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Situation | For full pension/allowance (per fortnight) | For part pension (pf) |

| Single | Up to $168 | Less than $1983.20 |

| Couple (combined) | Up to $300 | Less than $3036.40 |

| Illness separated (couple combined) | Up to $300 | Less than $3930.40 |

| Centrelink asset test limits for part age pensions from March 20, 2018 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Situation | Homeowners | Non-homeowners |

| Single | $556,500 | $759,500 |

| Couple (combined) | $837,000 | $1,040,000 |

| Illness separated (couple combined) | $986,000 | $1,189,000 |

| One partner eligible (combined assets) | $837,000 | $1,040,000 |

A rundown on the RAD

Retirees living in aged care facilities must make accommodation payments, but those living in their own homes, making use of home care packages, won’t need to make these payments. Naturally, the accommodation fees pile up.

There is both a refundable accommodation deposit (RAD) and a daily accommodation payment to be considered here.

It is not all too uncommon for a facility to ask for a one-off RAD of $500,000-plus. The average RAD is commonly reported as around $100,000 lower than this, however, that’s taking into consideration the many smaller aged care facilities in rural areas.

Half a million dollars is standard for capital cities. And this is currently a point of contention for many in the industry who are of the view there would be a better way for individuals to secure aged care accommodation, that’s fairer for both the individual and the provider. That’s likely to come up in the next round of aged care reforms.

For the unfamiliar, the RAD surfaced during the 2015 aged care reforms. It’s the new version of the old refundable accommodation bonds and, as was the case under the old system, the amount of refundable deposit is negotiated by aged care providers.

The RAD is exempt from the assessment of the age pension. And while there is an initial outlay of capital, a higher RAD can mean an age pension uplift as well as avoidance of interest charges, which would otherwise make their way into daily accommodation payments.

While it’s a one-off and fully refundable deposit, there’s no denying the RAD is a lumpy cost that’s difficult for many individuals and couples to produce. As touched on above, those who can’t find the funds for the RAD will be charged interest on their daily accommodation payments, and typically, at a very high rate – right now industry insiders report of a 5 per cent premium.

Sometimes this interest accretion will be the only option. Others may hold out hope for a government subsidised bed, and 40 per cent of beds are subsidised.

Hope and timing aren’t good friends though. Those who need extra care, and need it right now, may find their only option is to sell their most prized asset and possession – the family home.

.jpg)

Treatment of the family home

First, the birds take flight from the nest, and then, for some, the time comes for them to leave behind their precious nest egg too.

Discussions around the treatment of the family home are never easy. But residential aged care generally is not cheap. It’s important to establish realistic expectations about what will happen to the family home way ahead of time – in most cases, a decade before D-Day.

When it comes to the home, it frequently becomes a point of contention among family members.

Of course, the two most obvious decisions are whether to keep the home or sell the home.

There is no cookie-cutter approach for aged care. Due to both the finances and feelings concerned, it’s important to tread most carefully with the treatment of the family home. Whether it works best to keep the home, rent the home, or sell the home, will truly be dependent on personal circumstances. Aged care specialists and financial advisers come in handy at this stage.

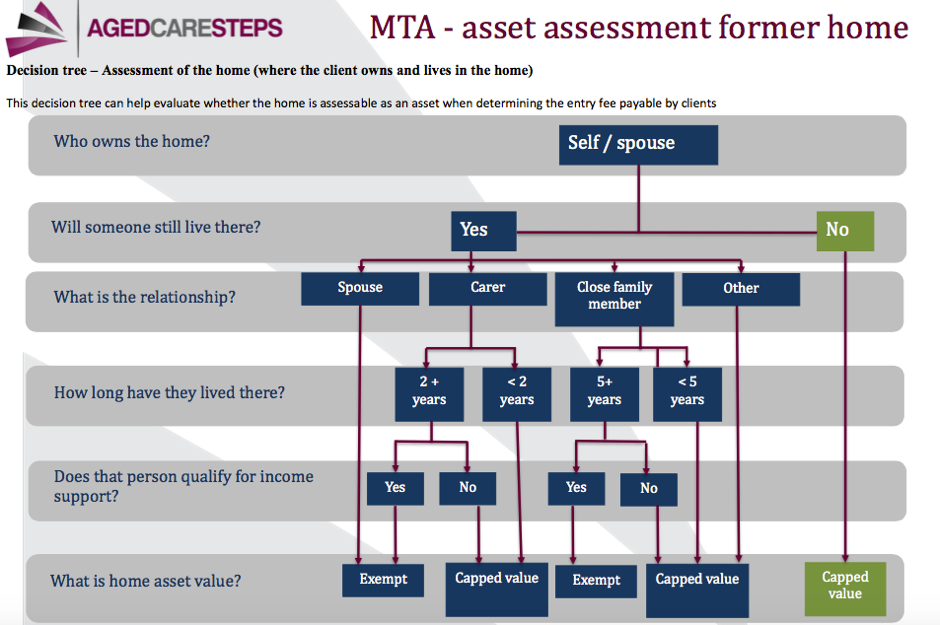

To get discussions rolling about the family home, the below decision matrix has been provided by Aged Care Steps.

Keeping the home

‘A can of worms’ is how Michael Rice, Chief Executive of actuarial research group Rice Warner, describes Australian aged care because of the family home implications.

“The system has become a can of worms because of how it’s funded,” says Rice.

“Most people think they will go into a retirement facility and sell the family home, but there are two issues with that – firstly, an increasing number of people will retire as renters because housing is becoming more unaffordable, and secondly, 70 per cent of people are married, and therefore, don’t retire at the same rate so they can’t really sell to make that contribution.”

The home remains an exempt asset from the means test indefinitely if a ‘protected’ person – that being a spouse or dependent child – remains living in the home. That’s an important point because, in most cases, a couple won’t enter aged care at the same time.

Individuals who keep the family home in their name will remain homeowners for two years after moving into an aged care facility, based on Centrelink and Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA) rules. The home may remain exempt beyond the initial two years if the client is putting down some of their aged care accommodation payment as a daily accommodation payment, or as a periodic payment for clients who entered before July 1, 2014, and some rental income is being received for the home.

The rental income of retirees who entered aged care before January 1, 2017 is exempt for Centrelink and DVA purposes, where a daily accommodation payment is made. But the rent is only exempt from the means-tested aged care assessment if the client entered aged care before January 1, 2016.

For aged care purposes, the rent received by any retiree who entered aged care on or after January 1, 2017 is assessable income. This was a big change that came into effect as those receiving more than a certain amount of rental income will see their pension entitlements eliminated entirely.

It’s important for rent to be paid directly to the former homeowner in any case, that being the individual in the aged care facility. If that rent is paid to another family member, trust, or estate, it may not qualify for any potential exemptions. The Social Security Act gives little more detail around this matter, even with regards to what qualifies as a rental payment. It could be assumed that an annual payment would suffice, rather than regular payments. Naturally, in most cases, this rental income will be put towards aged care, but the receiving individual is free to spend this on whatever they like.

As at March 20, 2017, for the purposes of the means-tested aged care assessment, the Government has capped the value of the family home at $162,087.20. But that figure is within earshot of the first aged care assets test threshold ($165,271.20). Therefore, where an individual is on track for a modest retirement, keeping the home can be detrimental to their financial security because it’s factored into this threshold testing for the pension.

A commonly asked question is whether it can be beneficial to transfer the home to another family member. Although ‘keeping it in the family’ is probably the preferred option for all, gifting provisions do apply, limiting what assets can be reallocated within a five-year window. Plus, transferring to another family member will incur capital gains tax.

Gifting assets can keep costs down, but it can equally compromise financial positions if done haphazardly. An individual can gift up to $10,000 per annum, or $30,000 over a rolling five-year period, before any excess will be assessed against them for a period of five years.

As Brown, aged care solutions specialist at Third Age Matters notes, it’s important to move assets outside of the five-year window before entering aged care.

“Even if you’re a self-funded retiree, who has never had any cash issues, if you start suddenly giving away property for less than market value, Centrelink will look at the last five years,” says Bina.

“Even if you’re a self-funded retiree with no links to Centrelink, ever, from now on you will be accessing government funding [in aged care]. That five years before entering aged care is most important.”

Selling the home

More often than not, the only option is to part with the treasured family home.

Considering one half of a couple usually stays in the home longer, the family home decision is often delayed. If the sale takes place after the remaining spouse has left the home, the proceeds will be disregarded for means test purposes for 12 months in most circumstances and 24 months in others – but only if there is an intention to use the proceeds to purchase another home. This isn’t the typical situation.

So, in all likelihood, the sale of the principal place of residence will have an immediate impact on daily accommodation fees. In a couple situation, the first member to go into care will pay means-tested fees; the second member also will pay fees if they enter aged care at a later stage. It’s best to get in touch with the Department of Human Services for a proper assessment of personal circumstances.

If the home was treated as the principal residence for the entire period of ownership, it’s very unlikely the individual will pay capital gains tax on the proceeds of the sale. On the other hand, renting out the home after entering care, and selling at a later stage, will probably result in a capital gains tax event.

In an aged care context, a homeowner may fall under a different definition to the standard. An individual is obviously a homeowner if they are living in a home to which they own legal title, fully or partially. However, special rules may apply if the retiree is living in a granny flat arrangement or a retirement village before moving into aged care.

In these cases, the individual doesn’t hold the legal title to the property, so there’s a chance their home will be considered an exempt asset under the assets test. Individuals who fit this bill can’t retain any degree of ownership over their former abode or rent it out.

.jpg)

Stay-at-home aged care

When given the choice, most people would prefer to just stay home. That’s all through life, but particularly, in their older age. While staying at home saves you money when you’re young, it’s the opposite when you’re older and in need of care.

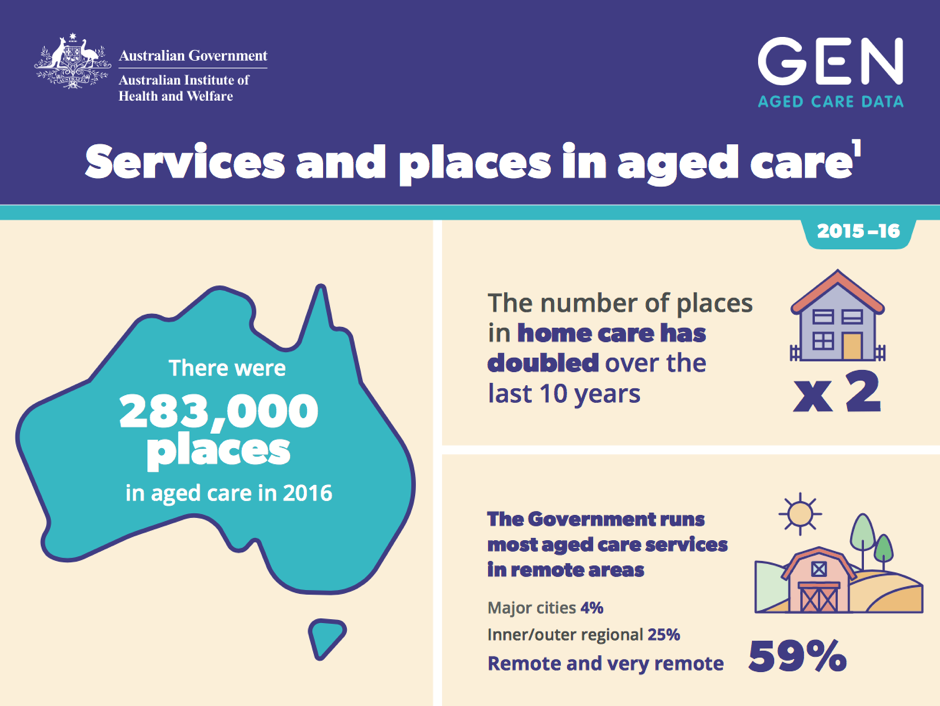

The Australian Government offers subsidised packages to help individuals pay for aged care at home. Yet, despite more and more packages becoming available, the package offered to any given individual typically won’t provide enough coverage.

Quick facts

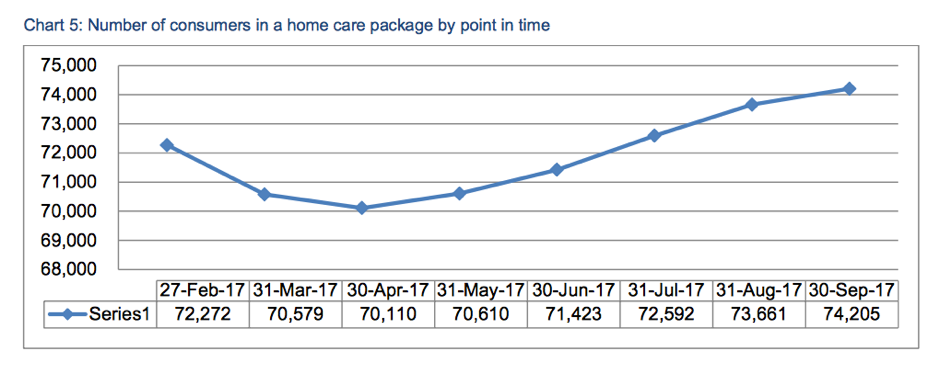

- Almost 105,000 Australians were queuing up for the Home Care Packages (HCP) program at December 31, 2017.

- Just 74,000 people were already in the program at September 30, 3017.

- Around half were on packages offering less care than they had been assessed for.

- Waiting lists for all packages were in excess of six months.

- The number of home care providers increased by 52.9 per cent in the 12 months to December 2017.

| Estimated maximum wait time for individuals entering the queue on December 31, 2017 by level and priority | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Package Level | First package assignment | Time to first package | Time to approved package |

| Level 1 | Level 1 | 6-9 months | 6-9 months |

| Level 2 | Level 2 | 6-9 months | 6-9 months |

| Level 3 | Level 2 | 6-9 months | 12 months |

| Level 4 | Level 2 | 6-9 months | 12 months |

The Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT) works out whether an individual should receive a package, which can range from just under $12,000 to just over $53,000 per year.

A tiered system

There are four tiers of home care. Every individual in the home care system can expect to pay a minimum basic daily care fee of $10.32 per day, included in their tiered package. An absence of this insinuates care will be inadequate and probably won’t meet the minimum requirements. As well, home care recipients will pay means-tested care fees if their total assessable income exceeds the income-free area, as detailed in our Costs of Aged Care section above.

At the bottom end, with a level one home care package, basic care can be provided for simpler tasks such as cleaning. A level one package, totalling nearly $12,000 all up, consists of a government subsidy of almost $8200, plus a mandatory contribution depending on annual income. This mandatory contribution registers as just under $3800 per year for someone on a full age pension. An individual on a level one package can only receive a maximum of around two hours of assistance each week.

At the other end of the care spectrum, an individual on a level four home care package is provided with high care assistance for help with things such as showering, dressing and administering medications. As tabled above, there is a long waitlist for this level of coverage, said to represent around 60 per cent of the total home care queue.

In March 2018, the Department of Health provided more details on home care packages on a granular level, including regional breakdowns.

Unfortunately, in more and more cases, even the maximum coverage as granted by government subsidies won’t be enough.

Someone who needs a health professional to watch them as they sleep every night would quickly push against the upper subsidised limit of coverage. Scaled down to an hourly rate, and dependent on the finer details, the upper limit only ends up being about 10-14 hours of care per week.

Family and friends can sometimes come to the rescue and fill the funding gap, paying a private provider for the extra care required on top of this 10-14 hours. Some may also find support in the interim through the Commonwealth Home Support Program (CHSP), which offers subsidised services for things like cleaning, gardening and transport. Costs will always vary, depending on the assessed individual and their service provider.

The private route

Some will seek comfort going the completely private route because, where government programs can churn through staff, directly employing a private nurse will likely deliver more stability, albeit at a greater cost.

From plenty of firsthand experience, Brown at Third Age Matters says individuals will find themselves out of pocket a minimum of $200,000 if they want someone in their home 24/7. A full-time nurse will typically cost $55 an hour at a minimum.

Others are taking matters into their own hands in a completely different way, keeping costs down by cutting out the middleman provider at certain touchpoints. Administration and case management fees can comprise up to 50 per cent of home care packages, so scheduling services yourself, or appointing a family member to do so, can save a portion of this.

“I think we have all realised, if your family can look after you for much of the day and just call in to supplement care, it’s a lot cheaper for the Government and everyone else,” says Rice Warner’s Rice.

“Until someone is in a wheelchair, needs help with the toilet, or requires assistance medically and frequently, there are ways around it. If you have a condition such as Alzheimer’s, you are broadly ok, and would probably prefer to stay at home.”

There is no cap on home care, unlike residential aged care. Basically, the Government will subsidise to a cost ceiling each year, and there’s no cap on what the stay-at-home individual pays after that.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. GEN. Canberra: AIHW.

The future of Australian aged care

Aged care reforms are always in the pipeline, and have ramped up significantly in recent years.

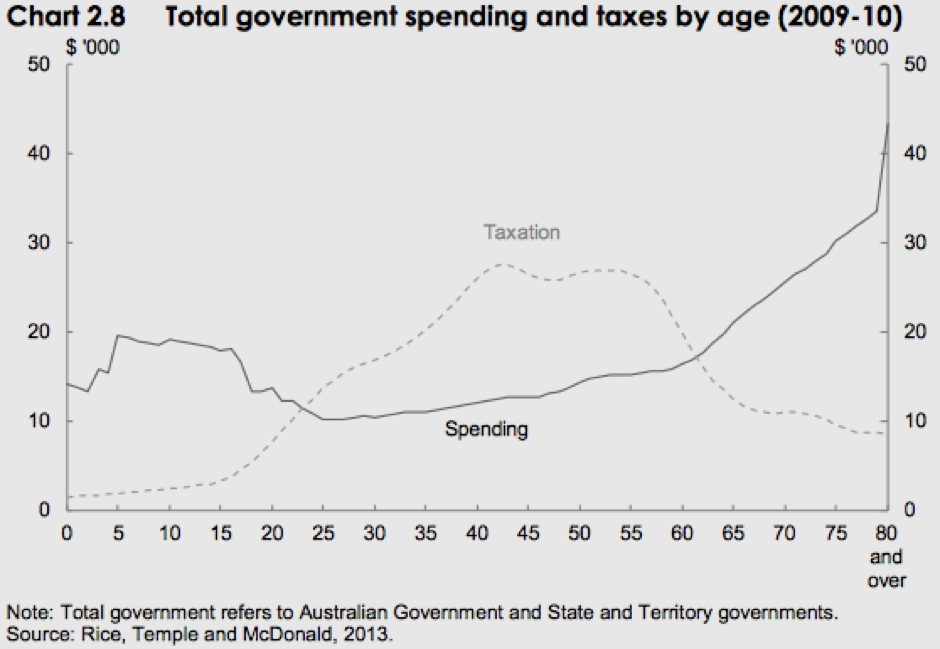

As noted in the 2015 Intergenerational Report released by Treasury, the government has committed to provide 125 aged care places per thousand people aged over 70. And that cohort is expected to almost triple in size in the next 40 years.

As such, Australian Government expenditure on aged care has nearly quadrupled since 1975, and is projected to nearly double again as a share of the economy by 2055.

Recent recommendations

In 2011, the Productivity Commission released Caring for older Australians, a report which prompted a suite of Australian Government reforms in 2012 under the Living Longer, Living Better (LLLB) review, which have continued to be rolled out. Even though things change every quarter on the aged care front, the last sweeping changes came into effect in 2015, suggesting further changes are on the cards.

With every review, questions are raised around the family home and whether it should be counted for full value, rather than capped at a certain amount.

But chiefly, the Council on the Ageing (COTA) is calling for the aged care system to become just as responsive to chronic, changing and increasing needs as it is to other crises.

First and foremost, given the popularity of the packages, COTA says the home care program needs the biggest shake-up of them all. Ultimately, the corresponding programs, Commonwealth Home Support and Home Care Packages, will be integrated by mid-2020. At least that’s according to the current timeline, which has blown out by a couple of years from the initial date of 2018. This integration is promised to open individuals up to greater choice and reduce waiting lists.

COTA is campaigning for a new higher level home care package, above the level four tier detailed earlier in this report, as that’s clearly falling short.

Ian Yates, chief executive of COTA Australia, estimated in September 2017 the funding gap to meet demand for home care packages was at least $1 billion a year, which could not be found from within the existing aged care budget.

“It’s not the elephant in the room, it’s the blue whale. It doesn’t get any bigger than that particular challenge,” Yates says.

However, of the 300 submissions received during the last round of consultations for home care reform, most stakeholders did not support the introduction of a level five package, and instead proposed increasing the funding of existing package levels.

In the mid-term, freer movement between package levels might become available. Many submissions also proposed the provision for very short-term subsidised support on call via a voucher system. As well, there’s a movement to make home care fees uniform, regardless of locations and service providers – the same fees for those of the same means.

Aged Care Steps director Biti claims the Australian Government subsidises between 60-70 per cent of all costs for aged care, and aged care providers often struggle to turn over much of a profit. In the future, she thinks retirement facilities covered by the Commonwealth might be able to choose what they want to charge, as independent facilities do now.

“The Government hasn’t made any indication they will act on submissions and do this or not, but they might determine it makes sense on a funding level, based on the service standards different providers have and the residents they are looking after,” Biti says.

“It could mean it becomes more expensive to live in some of those facilities – one less happy hour a week – so some people will need to shop around more. It would still be the way though that those under the threshold will be able to pay the lowest level.”

This is in line with the suggestions of Rice Warner’s Rice. He thinks it would make more sense to grade facilities on a star-basis, much like hotels:

“If you were at a 3-star place, it would be a certain amount per day, 4-star a step higher, and 5-star a way higher again. The Government could pledge to pay the first three months for everyone at a 3-star level – that would make more sense as people would understand it more.”