Shining a light on the damaging effect of a high dollar

Australia hardly needed a 326-page review of the Australian automotive industry -- not after Ford, Toyota and Holden announced plans to exit the market by 2017. Yet the realities of these closures have yet to settle in; unfortunately, the sector is set to lose as many as 40,000 jobs over the next few years, which -- combined with job losses in the mining sector -- creates a risk of greater structural unemployment.

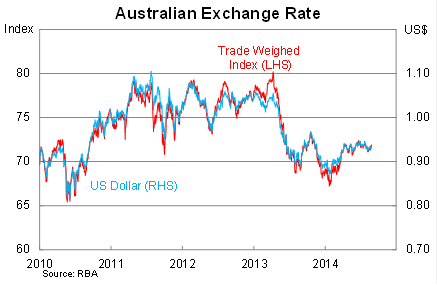

The demise of the Australian motor vehicle sector has been a long time coming but it provides a timely reminder of the competitive challenges facing Australian businesses in a high-wage, high-dollar environment.

At first glance, the benefits of a high dollar seem fairly obvious. It directly improves your purchasing power, resulting in cheaper goods and fantastic import prices for households and businesses alike.

It’s a great deal. What could go wrong?

Unfortunately, the dynamics of our exchange rate are more complicated than that. You might love cheaper prices from Amazon but how do you feel about losing your job? Or settling for a lower wage? Because these are the trade-offs that many businesses continue to face.

Australian businesses have a mixed relationship with the exchange rate. On one hand, firms who import intermediate goods or services have benefited significantly from the high terms-of-trade. But for other firms -- particularly those competing against cheaper imports or selling goods abroad -- the past decade has been a struggle.

Perhaps the most visible victim of Australia’s elevated exchange rate has been the Australian motor vehicle industry. Facing high wages and relying on government support; the high dollar was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

According to the Productivity Commission, the collapse of the industry will result in up to 40,000 people losing their jobs over the next few years. The pain will be ‘concentrated within particular regions, such as North Adelaide, parts of Melbourne and Geelong’.

Job losses are nothing new for the car manufacturing sector or for those regions. Employment in motor vehicle manufacturing fell by more than 45 per cent between 2005 and 2012, which also flowed through to component manufacturers who cut 30 per cent of their workforce.

The Australian labour market remains fairly dynamic -- the commission notes that during the year to February 2013, “about 355,000 people were involuntarily retrenched across Australia” but the unemployment rate during that time rose by just 0.2 percentage points. As a result, the PC takes a fairly favourable view; “within a year about two-thirds are likely to be re-employed on a full, part-time or casual basis”.

Even if the commission scenario eventuates -- and I have my concerns -- most of those jobs are going to be in lower paid positions. The same can be said of the mining sector; ANZ and NAB estimate the mining sector may lose between 75,000 and 100,000 jobs over the next couple of years. For the Australian economy to successfully absorb these losses, employees will have to accept lower wages and conditions.

The greater concern though might be structural unemployment, which will result in higher long-term unemployment. Structural shifts in the economy -- such as a shift away from manufacturing or the end of a mining boom -- are often associated with a more persistent rise in unemployment.

The manufacturing sector is poorly positioned to absorb these losses. The high Australian dollar continues to weigh on activity, and capital expenditure -- a good measure of whether the industry will expand and take on new workers -- is set to fall sharply in the 2014-15 financial year (A weakening investment outlook for businesses; August 28).

Furthermore, employees within the motor vehicle sector may find their skills and experience a poor fit for the market. About 34 per cent of employees were in lower-skilled occupations (over twice the average across all industries), while 40 per cent were aged 45 or over.

The eventual fallout will largely depend on the flexibility of the Australian economy; can we produce enough new jobs and investment opportunities? As is so often the case, this is a problem that can be solved by stronger growth and higher productivity; however, the state and federal governments also have a role to play by supporting the transition.

The motor vehicle industry is in many ways a cautionary tale. At times it may have been its own worst enemy and certainly its reliance on government handouts hardly endeared them to the public. But the lesson we should take from this is that a high dollar has imposed a considerable cost on Australian businesses, resulting in a loss of international competitiveness. It is a situation that must change if we are to absorb these job losses and create new opportunities moving forward.