Renters won't bail out housing investors

Remember the buzzing national mood around the time of the Sydney Olympics?

There was Cathy Freeman in her hooded suit winning gold over 400 metres. There was the army of high-spending creative types using dot.com investors’ money to have the time of their lives. And out in suburbia, Australians were getting their first real taste of the property boom to come.

As one national newspaper noted at the time: “There are many who want to believe residential property in Sydney and Melbourne will continue to boom after the Olympics... But with rising vacancy rates (properties sitting on the market week after week without being let) and the prospect of a slowdown in the US, this scenario is unlikely.”

Nobody could have predicted how wrong that statement later became. Prices leapt ahead at a rate not seen since the post-WWII property price spike.

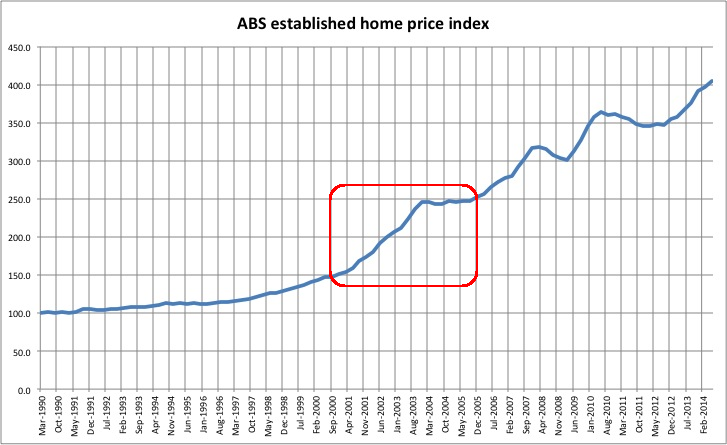

Between the Olympics and early 2004 prices increased by 67 per cent and Australian TV audiences learned the fundamentals of the boom -- prices always go up, borrowing up to your limit was the only sensible thing to do, and the actual rental yield on your investment property was next to irrelevant.

But was it? That Olympic growth-spurt, like Freeman out of the blocks, was followed by two years of almost zero capital growth -- just like the runner, sitting on the track after the race and going nowhere (see chart below).

And in the absence of capital gains, investors need to take a second look at yields -- they become, by default, value investors rather than growth investors.

In the run-up to the turn-of-the-century property boom, something quite striking had happened to rental yields. A national average gross rental yield of 7.8 per cent in 1996 slipped to 4.0 per cent by early 2004.

The ‘demand’ for the existing housing stock was not so much from extra people wishing to live in the houses, but from investors keen to hold assets with rapidly inflating values -- hence the newspaper quote above being a natural enough mistake.

From an investment perspective, that problem with that scenario is that rents are mostly a function of householders’ ability to pay (wage growth) and the cost of ‘renting’ capital from a bank to buy their own home (interest rates).

So when capital gains go flat, investors have to be patient to see yields catch up -- they can’t just bully renters into paying more.

In recent weeks there have been some alarming data released on yields. RP Data figures show Sydney’s price boom has pushed gross yields down to 3.6 per cent for houses and 4.5 per cent for units.

In Melbourne, it is even worse -- 3.2 per cent for houses and 4.2 per cent for units.

And remember these are gross yields. Once finance, maintenance and management costs are factored in the real yield is negative -- and the investment only makes sense by adding together capital gains and the investors’ tax refund from negative gearing.

The question the RBA has posed recently -- as well as dozens of media commentators -- is whether it’s worth buying a home to live in, or rent.

That is obviously a very different question to whether or not to buy a second property, to benefit from low rates and the ATO’s generous tax breaks.

The widely reported answer supplied from the RBA was: “... many observers have suggested that future house price growth is likely to be somewhat less than this historic average. In that case, at current prices, rents, interest rates and so on, the average household is probably financially better off renting than buying.”

But what about investors who are trying to decide between investing in housing or investing in a stockmarket that could be hit by capital flight when the US finally ends its super-low interest rate regime? (see: The toxic combination turning investors off Australia, September 23.)

The RBA has not given much of an answer, other than to note that rental yields and capital growth move for different reasons.

In the same report quoted above, the RBA noted: “The insensitivity of our results to changing assumptions about growth in rents contrasts with the literature on stock market valuation, which finds substantial sensitivity to assumptions about earnings growth. The main reason is that studies of equity valuation typically assume that higher growth in earnings feeds back into greater appreciation whereas we do not.”

Translated, that means that when sharemarket dividends (or expected dividends) rise, that yield is pretty quickly factored into the share price by analysts and investors.

But when house or apartment rents rise or fall, we have grown accustomed to ignoring them -- house prices have been moved more by animal spirits than by the notion that the asset will prove ‘profitable’ now or in the future. A profitable housing investment? How 1996!

And that could prove to be a huge problem if the pattern of 2000-2004 is followed by a couple of flat years in which rental yields ‘catch up’.

The idea that an interest rate rise next year can simply be passed on to defenceless renters, is a silly one. The rental market follows the laws of supply and demand much more faithfully than do property prices.

A period of flat capital growth, with stubbornly low rental yields in Melbourne, Sydney and perhaps elsewhere, will give many investors pause for thought.

Perhaps the investment laws we learned in the buzzing days around the Sydney Olympics were not quite right after all.