Re-emerging markets?

| Summary: Recent emerging market (EM) listed company returns have disappointed despite strong regional growth fundamentals. Some of this has been masked by currency effects. With 40% of world GDP coming out of these markets and growing, you need to decide what EM exposure your portfolio should have. |

| Key take out: A strong Australian dollar and weakened emerging market currencies should make you wonder whether now has become a better time to invest in emerging markets. |

| Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Asset allocation. |

Let’s be honest. Developed market economies are stuffed. Lax financial discipline has seen most governments make promises they can’t fund, and will spend years trying to wiggle out of. Their population is ageing and shrinking as children have shifted from being a retirement asset to a luxury item. Once debt stopped being treated as a four letter word, people and governments in developed economies gorged on it. At best, we’ll be preoccupied for many years repaying it. None of these things are pro-growth - the fuel of long-term company profit and share price appreciation.

However, in the other part of the world where 80% of people live and now 40% of world GDP is produced, growth prospects are much better. Indeed, this region’s share of GDP was only 20% a decade ago and two-thirds of future global growth is projected to arise from there. Having had their own GFC in the late 1990s developing countries have only one-third the debt/GDP of so-called advanced economies.

Better growth fundamentals = better returns? Not lately

So you should expect companies operating in and listed in markets with better growth fundamentals should perform better. However, you would be wrong (or as we’ll see later, wrong over recent time and in local currency).

Over the last 12 months, sharemarket returns from companies listed in emerging market countries delivered a lesser 17% return versus 25% and 38% for companies listed on the Australian and other developed country exchanges respectively. Over three years the comparison is worse still. Emerging market companies returned a meagre 2% annualised return versus 10% and 14% per annum for Australia and other developed markets.

For the last 20 years, you can see from the below chart the price investors have been willing to pay for profits sourced from companies listed in developed economy sharemarkets averaged a premium and rising 14 compared to a discount and recently flat 9 times for those from emerging markets.

Emerging market versus developed market company P/E over the last 20 years: Source T Rowe Price.

This suggests two things: (1) a lot of the recent growth in developed economy companies’ share price has been driven by price growth or P/E expansion, which like snorting QE is not sustainable; and (2) in a world where there are few investment bargains around, perhaps emerging market companies are it?

Australian investors prefer developed markets

Australian self-directed including SMSF investors have a strong “home country bias” with their investment selection. Some don’t invest in International shares at all. The reasons can be unfamiliarity, lower franked yield, poorer past performance or difficulty investing directly.

Those that have waded offshore do so mainly through managed and “unmanaged” funds which focus on developed economy companies.

Magellan and Platinum are two of Australia’s most popular active international equity fund managers. Magellan, the new Platinum, has certainly been in the right place at the right time with a style that favours in demand defensive and consumer branded companies. However, investors take note as past returns aren’t a predictor of future returns and these style biases can fall out of favour.

With the rise in indexing many have been investing in international share index funds like from Vanguard. However many don’t realise that while this funds invests in more than 1,500 overseas companies they are only those in developed market economies, not developing.

Most ways you look at it many Australians aren’t investing much in companies trading in emerging market economies with better growth prospects. This is a shame because, over the last 10 years, developing market companies were a better performing, diversifying equity investment than developed market companies.

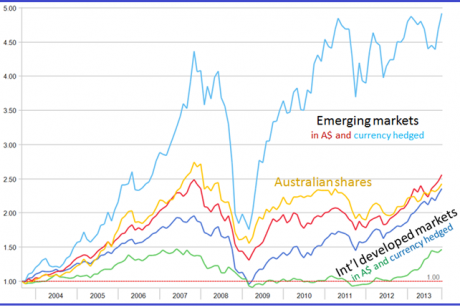

Growth of a $1 invested in Australian shares (gold), emerging market shares (in light blue currency hedged and in red more commonly unhedged form) and all developed market country companies ex-Australia (dark blue hedged and in green unhedged) over the last 10 years. The strengthening of the A$ and fall in emerging market currencies have hurt unhedged investors. Source: Professional Wealth and thanks to Aberdeen for the custom calculated EM currency hedged index.

How to get your EM fix

By now, in case you are wondering, what is an emerging market? So are others. Wikipedia documents the history of this changing classification and show that amongst the various index suppliers like FTSE, MSCI, S&P, Dow Jones there is disagreement what to include. There is no disagreement the biggest emerging markets include Brazil, Russia, India and China (the so called BRICs) but also include many other countries in Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa. South Korea and Taiwan are under review to become reclassified as developed (happy) and Greece is submerging back it seems (sad).

The top 10 holdings of Vanguard’s emerging market fund include a Korean automaker and electronics firm, a Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer, a South African media company, Chinese mobile, banks and energy companies and a Mexican phone company.

The only practical way for Australian investors to get an EM fix is by investing through a fund.

The big three active funds, with about a billion dollars each under management, are offered by Colonial, Aberdeen, and Lazard. Not surprisingly these have been the top performers over time. (See Cliona O’Dowd’s article Picking emerging market winners).

Vanguard, Dimensional, Blackrock and Realindex offer a lower cost index, or index-like way to invest. Vanguard’s buy-nearly-everything indexing strategy placed it ninth out of 16 and third out of six compared to others over five and 10 years, respectively. This suggests even in emerging markets indexing has become a reasonable strategy to apply if you don’t think you can pick the winning fund manager or fund managers can’t pick winning countries and companies.

In case you’re wondering about currency hedging, Australian funds only offer unhedged products.

While it’s easy and currently profitable to hedge the Australian dollar against the greenback, euro and pound, it’s hard to do that versus the real, ruble, rupee, renminbi … which is why fund managers don’t.

Anyway, if you think that the emerging economies have done a better job than Glenn Stevens talking down their currencies, then now is not the time to hedge your exposure to emerging market company investments. EM currencies are cheap and the Australia dollar is expensive, so buying is good and so will be your returns if this reverses.

How much EM do you need?

If you want your portfolio to match the world stock market capitalisation then you would allocate about 15% of your equity portfolio to emerging markets … oh and 3% to Australia. Since you’re highly unlikely to do the latter, then perhaps 15% of your non-Australian equity exposure should be emerging market focused as a starting position.

Of course, another answer is nil. Since 40% of world GDP is produced in emerging markets but their stockmarket capitalisation is about 15%, then we can surmise that a little over half the profits from this region are being captured by unlisted entities and multinationals (for instance, profits from selling iphones in Brazil are accessed on the US NASDAQ under the stock symbol AAPL). It’s estimated that about 15% of US company profits are earned trading in emerging markets. So just as you might buy BHP, nab and CSL hoping to get some international exposure into your portfolio, you could just invest in international developed markets and skip emerging market listed companies. Australia’s commodity intensity and China export dependency makes our market perform like an emerging market so some might argue you need not double dip.

Emerging market stocks as a whole are more volatile because of fluctuating concerns about political risks and protectionism, currency and controls, inflation and market fairness. This adds up to a higher standard deviation for emerging market shares which has been 18% compared to 13% for Australian and currency-hedged International shares. If you are designing a portfolio to minimise volatility (see The silent killer of retirement savings) then emerging markets are an expensive addition and you would minimise their exposure.

As a benchmark growth fund, the Future Fund had at 30 September a substantial 8% of assets in emerging markets, or one-quarter of their global equity allocation. That 8% is nearly equal to their 10% allocation to Australian equities. With an Australian/International equity mix of 1:3, you can’t accuse them of having a patriotic home bias!

Lastly there are a few other ways to invest to capture benefit from growth in the region.

Sydney infrastructure specialist RARE offers a fund that invests solely in infrastructure companies who source the majority of their earnings from emerging markets. They propose that unexciting utilities and toll roads provide a less volatile way to capture profits.

Rather than own emerging market companies, you can instead lend to them and their governments. PIMCO’s emerging market bond fund delivered an impressive 11% annualised five year return however it included a -2% return the last 12 months. Unfortunately buying emerging market bonds can prove to be like checking your money into Hotel California. Then again what credit certainty can California and the US boast about?

In recent times emerging market company prices and currencies have performed on a relative basis more like submerging markets. If you’re a contrarian investor, perhaps that’s your buy signal? Alternatively if you are a strategic asset allocator and you are excluding them, then you need to ask yourself why.

Doug Turek is the Principal Advisor of family wealth manager Professional Wealth (www.professionalwealth.com.au). Funds referenced here are for educational purposes and don’t constitute a product recommendation.