MYEFO is Hockey's chance to set the record straight

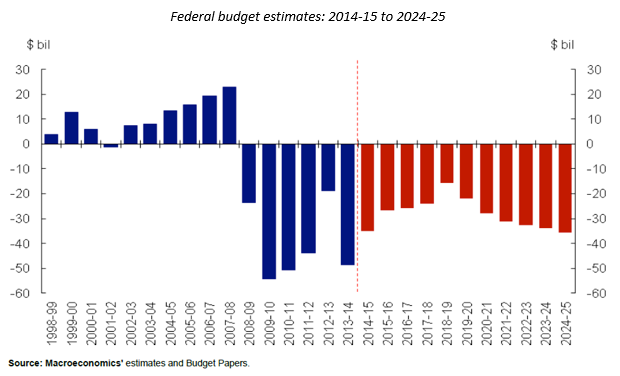

The December Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook promises to be a doozy. Recent analysis by consulting firm Macroeconomics indicates that a hostile Senate and a sharp decline in iron ore prices have blown a $51 billion hole in Treasurer Joe Hockey's first budget.

According to Macroeconomics, the deficit will increase to $47.8bn in the 2014-15 financial year (from May estimates of $29.8bn) before easing to a deficit of $24bn in the 2017-18 financial year (compared with earlier estimates of $2.8bn).

It's difficult to know where to lay the blame. On one hand, Hockey was the one who delivered a budget that was almost universally regarded as unfair. Independent analysis has left us in little doubt that the budget left too much of the heavy lifting to those least able to bear it (Budget pain and Senate strife; October 13).

But it was the senate that decided to play politics. According to Macroeconomics, “there is now around $11bn in annual budget savings by 2017-18 held up in the senate.” Given the choice between reform and populism, Bill Shorten and Clive Palmer have overwhelmingly pursued the latter.

Of course the Coalition must take direct blame for scrapping the carbon tax -- which at the May budget was estimated to raise $7.3bn in tax revenue in the 2013-14 financial year -- and for repealing the resources tax, which was hardly lucrative but still supported the bottom line.

In addition, “the Treasurer faces up to $10bn in unfavourable parameter variations annually by 2017-18.” The end of the mining boom and the associated fall in our terms-of-trade is weighing on income and nominal GDP growth. According to Macroeconomics, “not even bracket creep will help return the budget to surplus with such low wages growth.”

The MYEFO will be an opportunity for the Treasurer to set the record straight. There is no point in sugar-coating Australia's predicament or -- as has been the case with federal budgets since the global financial crisis -- assuming the most optimistic scenario for revenue.

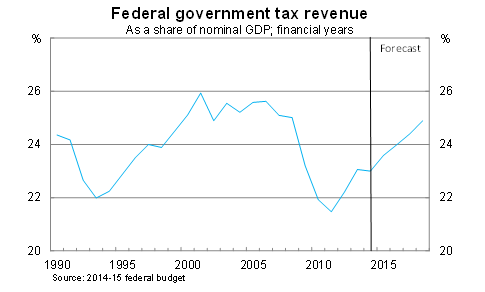

In the 2014-15 budget, the federal government assumed that tax revenue in 2017-18 would return to 24.9 per cent of nominal GDP (from 23.1 per cent of nominal GDP during the 2012-13 financial year). As I noted after the release of the Commission of Audit, these assumptions are hopelessly optimistic (The missing piece of the audit puzzle; May 1).

The Commission -- and the federal government later in May -- made the mistake of assuming that tax revenue would simply push back towards its long-term trend. That's a fairly common trick within the forecasting game -- I've done it myself countless times -- but it's a poor technique during times of structural change.

The fact that each budget since the financial crisis has been met with revenue downgrades indicates that there is an existing bias at both Treasury and within the halls of power. The Labor Party was crucified for over-promising and under-delivering and now the Coalition has fallen into the same trap.

In the absence of widespread tax reform, there is no good reason to believe that tax revenue will return to its pre-crisis level. What was the norm during the glory days when the terms-of-trade was high and demographics were favourable cannot be replicated going the other way. It's silly to pretend otherwise.

Given the existing parameters and long-term trends, it is reasonable to conclude that the federal budget will remain in deficit for the next decade and, if that occurs, another decade after that is all but certain.

If that doesn't drive home the need for tax reform I don't know what will. But if you need another reason, consider the fact that the Productivity Commission estimates that without reform, federal spending on health care and aged care services (including the pension) will increase by 5.7 percentage points of nominal GDP by 2059-60.

Something has to break. Either we raise taxes (in my opinion the most likely scenario) or we cut spending in other areas. Perhaps our children can receive a more expensive or inferior education? Perhaps we take short-cuts on infrastructure investment? Perhaps we simply shift all responsibilities to the states and hope they are more open to reform?

The maths in the federal budget doesn't make any sense and the Treasurer will have an opportunity to fix that in December. We need to have a mature and open budget debate; the public needs to know that we don't necessarily face an immediate budget crisis but we certainly face a long-term one.

They need to know what options are on the table and we need both major parties to recognise the need for budget and tax reform. That realistically requires another election, but in the meantime the Treasurer has MYEFO and he should use it to full effect.