Modelling economic balance like it's 1975

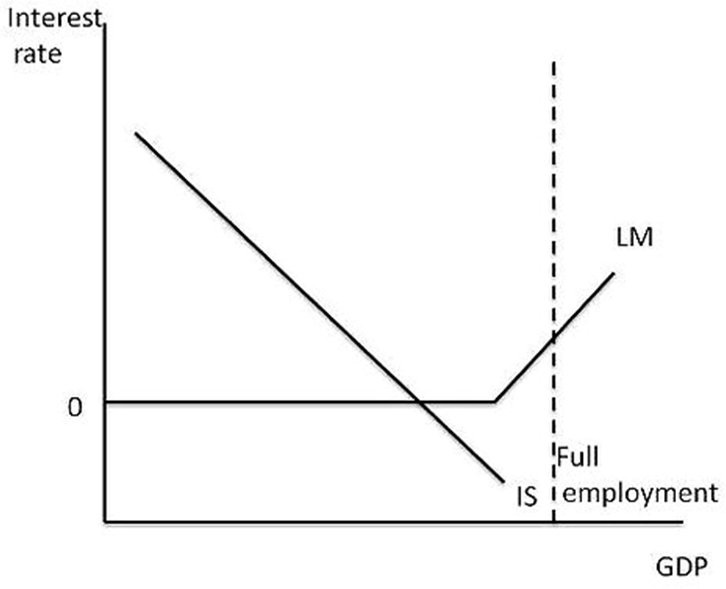

OK, my bad: I had interpreted Paul Krugman as giving a dis-equilibrium interpretation of IS-LM in his explanation for our Lesser Depression. Instead, as he explains here, he applies a standard equilibrium interpretation of the model: in a crisis like ours today, the economy is in equilibrium with less than full employment. In the IS-LM model, this is represented by the IS and LM curves intersecting (on the zero lower bound) at a point below full employment (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The economy is in equilibrium at the point where IS & LM intersect, below full employment

Given that error of mine, Krugman apparently stopped reading pretty much at that point – which is a pity, because the part I really wanted him to read was John Hicks’s considered opinion of IS-LM, about four decades after he first invented the model, which seeks to explain the relationship between interest rates on one hand and real output, in goods and services and money markets on the other.

The comments are directly relevant to attempting to use IS-LM to give an equilibrium interpretation of economic crises. Here’s Hicks in 1981:

“Applying these notions to the IS-LM construction, it is only the point of intersection of the curves which makes any claim to representing what actually happened (in our '1975')…as the diagram is drawn, the IS curve passes through the point of intersection; so the point of intersection appears to be a point on the curve; thus it also is an equilibrium position.

“That, surely, is quite hard to take. We know that in 1975 the system was not in equilibrium. There were plans which failed to be carried through as intended; there were surprises. We have to suppose that, for the purpose of the analysis on which we are engaged, these things do not matter. It is sufficient to treat the economy, as it actually was in the year in question, as if it were in equilibrium. Or, what is perhaps equivalent, it is permissible to regard the departures from equilibrium, which we admit to have existed, as being random.

“There are plenty of instances in applied economics, not only in the application of IS-LM analysis, where we are accustomed to permitting ourselves this way out.

“But it is dangerous. Though there may well have been some periods of history, some “years,” for which it is quite acceptable, it is just at the turning points, at the most interesting “years,” where it is hardest to accept it.”

So in this paper, Hicks, the originator of the IS-LM model, rejected it as a means to model a crisis like the one we’re in, because he couldn’t accept the model’s assumption that the economy is in equilibrium at all times. Instead, especially when crises like the one we’ve been in since 2008 strike, Hicks believed the economy was in disequilibrium – and a large part of his paper (the part I was channeling in my previous posts) was devoted to showing that IS-LM can’t be used to model a disequilibrium situation.

His conclusion was that macroeconomics had to be a study of disequilibrium processes, using appropriate dynamic tools. He didn’t put it elegantly – Hicks was not in Keynes’s class as a writer – but there’s no mistaking his rejection of equilibrium analysis in macroeconomics:

“When one turns to questions of policy, looking toward the future instead of the past, the use of equilibrium methods is still more suspect. For one cannot prescribe policy without considering at least the possibility that policy may be changed. There can be no change of policy if everything is to go on as expected – if the economy is to remain in what (however approximately) may be regarded as its existing equilibrium.

“It may be hoped that, after the change in policy, the economy will somehow, at some time in the future, settle into what may be regarded, in the same sense, as a new equilibrium; but there must necessarily be a stage before that equilibrium is reached. There must always be a problem of traverse. For the study of a traverse, one has to have recourse to sequential methods of one kind or another.”

Given these passages, I think there’s no doubt that Hicks would reject Krugman’s attempt to use IS-LM to explain the current crisis. And yet at the same time, Krugman is quite right to argue that his IS-LM and New Keynesian approaches to macroeconomics are far more realistic than the Chicago School/Freshwater/Real Business Cycle approaches of people like John Taylor, Robert Barro and so on, whom he lambasts here. So what’s going on?

The problem is that over the last half century, economics has regressed rather than evolved. Hicks had hoped that economics would progress to dynamic analysis, but rather than going forward to dynamics, macroeconomics went backwards towards the equilibrium thinking that dominated economics before Keynes. In that vision of the world, even the Great Depression was an equilibrium event – meaning, wait for it, that the increase in unemployment during those years was a rational response by workers to choose leisure over labour!

I kid you not: consider these passages from the winner of the 2004 Nobel Prize, Ed Prescott:

“The key to defining and explaining the Great Depression is the behaviour of market hours worked per adult… Briefly, market hours worked per adult dipped to 72 per cent of their 1929 level in 1934 and remained low throughout the 1930s…

"From the perspective of growth theory, the Great Depression is a great decline in steady-state market hours. I think this great decline was the unintended consequence of labor market institutions and industrial policies designed to improve the performance of the economy. Exactly what changes in market institutions and industrial policies gave rise to the large decline in normal market hours is not clear…

“In the 1930s, there was an important change in the rules of the economic game. This change lowered the steady-state market hours. The Keynesians had it all wrong. In the Great Depression, employment was not low because investment was low. Employment and investment were low because labour market institutions and industrial policies changed in a way that lowered normal employment.”

This is the sort of drivel that Krugman fights on an almost daily basis – and in that struggle, more power to his elbow. New Keynesian economics – and for that matter, Hicks’s IS-LM – is better than this nonsense, in part because it would be difficult to be worse.

So why do I and other Post Keynesians like Swedish economist Lars Syll present Krugman with a second front on which to fight? Because we want to continue the agenda John Hicks set in this important but neglected paper: to make macroeconomics a study of dynamics rather than equilibrium, because the real world is not in equilibrium, and never has been.

But enough of fighting: as I concluded in my last post, Krugman isn’t about to abandon equilibrium – and his reply to me has made that even clearer. The task of building a genuinely dynamic macroeconomics will have to be undertaken by others.