Look again - interest rates are rising

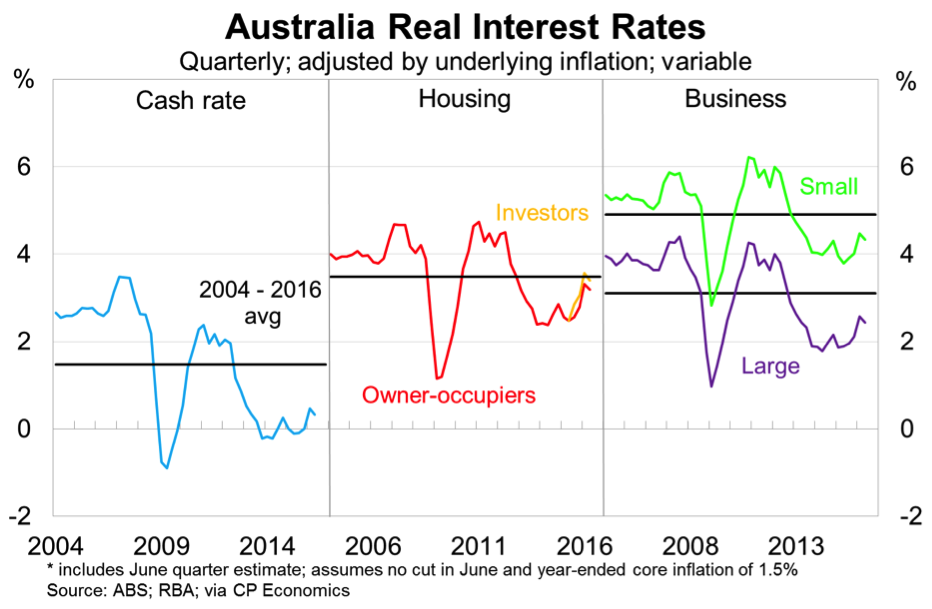

Summary: While the RBA dropped its cash rate to a "record low" level of 1.75 per cent in April, it's important to note that in real terms, mortgage rates have increased in real terms over the past two years and now sit just below the long-term average. Meanwhile, spreads on new mortgages have become wider in the face of banking regulation. |

Key take-out: Nominal interest rates may fall further, but it's unlikely that real interest rates for both households and businesses will reach the lows of 2014. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economy. |

Earlier this month the Reserve Bank of Australia cut the cash rate by 25 basis points to 1.75 per cent. As many of you will know this is widely regarded as the lowest level in Australian history.

Except that it isn't. Not by a long shot.

Modern economic and financial theory is founded on the idea that it is “real” rather than “nominal” interest rates that affect economic activity. In analysing whether monetary policy or any other interest rate is tight (high and getting higher) or accommodative (low and getting lower), we must also consider what is happening to inflation.

Underlying inflation came in at 1.5 per cent over the year to the March quarter. This is the weakest result in at least 30 years. The path towards record low inflation has driven the real cash rate, as well as real mortgage and business rates, to their highest level in over two years.

The real mortgage rate for owner-occupiers has increased by 81 basis points over the past two years and sits just 29 basis points below its long-term average (since 2004) of 3.5 per cent. Mortgage rates for investors are even tighter, sitting just nine basis points below the long-term average. Businesses haven't escaped either, with tighter policy actively discouraging new investment.

Another important factor has been increasing spreads on mortgage and business loans. Spreads on all loan types rose significantly following the onset of the global financial crisis. Banks required a greater return for each unit of risk.

The spread on new mortgages, however, has continued to rise even as perceived risk has moderated. The spread on new mortgage loans for investors, for example, has jumped by 50 basis points since March last year, accounting for 60 per cent of the rise in the real mortgage rate for investors over that period. For business loans, spreads have been relatively stable over the past half-decade.

There isn't much that investors can do about wider spreads. To a large extent it reflects a regulatory environment where banks are encouraged to hold greater capital against their asset base. However, investors would be unwise to ignore the possibility that banks will at least partly claim the benefits of any future rate cuts. It's highly unlikely that mortgage or business rates will touch their low from two years ago.

There are several key questions that investors need to ask themselves:

1. Is lower inflation temporary or permanent?

2. What does this mean for monetary policy?

3. Has higher real interest rates been incorporated into valuations?

The RBA believes that underlying inflation will remain below their annual target range of between two and three per cent through to at least mid-2018. There is a transitory element, driven by low oil and fruit prices, but lacklustre wage growth is the main reason that underlying inflation has fallen to its lowest level in at least 30 years.

As a result, investors should feel free to treat low inflation as a relatively permanent shock.

Lower inflation will, ceteris paribus (all things being equal), reduce company earnings growth and increase the cost of household and business debt. On the other hand, it helps older Australians who primarily rely on low-risk savings.

However, the situation becomes more complicated given lower inflation doesn't occur in a vacuum. Persistently low inflation, to the extent that it weighs on company earnings or hurts household and business balance sheets, would almost certainly trigger further cash rate relief from the RBA.

The RBA's forecasts for inflation imply that the bank will cut their official cash rate on at least two more occasions, dropping the cash rate to 1.25 per cent, with the first move likely to occur in August and the second in early 2017.

Given the market is pricing in only a 28 per cent chance of a second rate cut, a clear mispricing, there is clearly some upside risk for both equity and bond investors. It could prove sufficient for the ASX 200 to break out of its recent range and for Australian government bond prices to rise to their highest level in history.

The big beneficiaries will be Australian exporters as the Australia dollar heads below US70c. Manufacturing and tourism are two sectors that are sensitive to changes in the dollar, while I believe it's worth steering clear of volatile mining stocks as speculative activity in commodity futures fade.

It's important to remember, however, that from here on out the RBA is mainly acting to offset the damage done by low inflation. Nominal interest rates will fall further but real interest rates, for both households and businesses, will likely remain above their low from 2014. So while there is upside for asset prices, it is unlikely that the ASX 200, for example, will test its high from early last year. At least not anytime soon.