Lessons for China as a city's housing market hits the floor

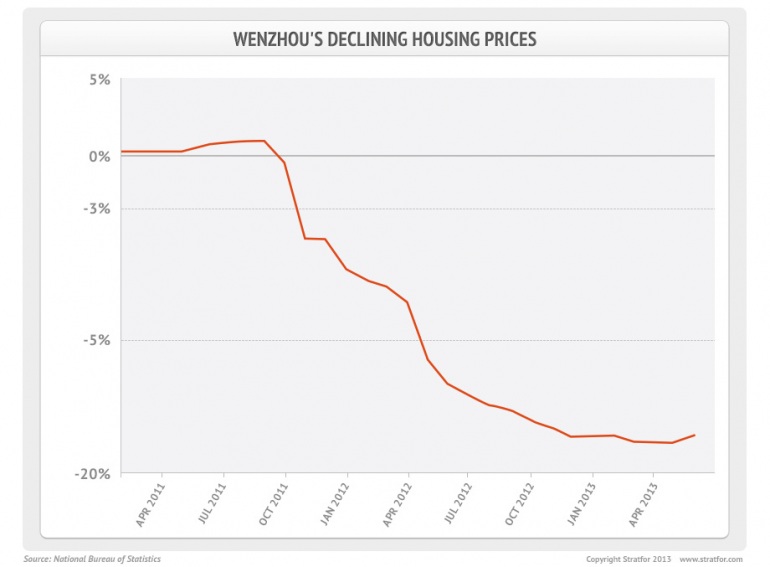

Sharply falling real estate prices in the coastal city of Wenzhou in recent years represent another blow to the city's once-legendary local private economy. The city was hit hard by declining competitiveness in manufacturing and a wave of defaults on loan guarantee mechanisms starting in 2011, a process that forced many local businesses into bankruptcy.

Over the past decade, Wenzhou has witnessed its own volatile transformation from a flagship of China's booming low-end manufacturing economy -- famously cemented in the so-called "Wenzhou model" of small-scale, profit-oriented private enterprise -— to a symbol of China's speculative property bubble-driven economy. Against this backdrop, the painful correction now underway in the Wenzhou model might be seen as a microcosm for the enormous challenges facing both manufacturing and property sectors throughout China in the years ahead.

Property prices in Wenzhou have been falling for 23 months straight, making it the only major Chinese city to record an outright decline in its real estate market in recent years. As of August, prices for Wenzhou's new commercial properties have reportedly declined by 30-40 per cent compared to 2009-2010 levels. This drop has further driven property owners to sell their mortgaged properties, many of which have fallen in value to well below the mortgages themselves. According to some estimates, more than 10,000 mortgaged properties have been disposed of (mostly confiscated by either banks or courts) so far this year — nearly equal to the total number of new properties built in 2012.

Wenzhou represents an extreme in the spectrum of Chinese urban property markets, most of which are not highly leveraged. (Chinese homebuyers typically pay a far higher share of the total property value up front, in cash, than their U.S. counterparts.) Wenzhou's highly leveraged property markets intensify the risk of the local property market bursting.

At the same time, the localised nature of lending markets in Wenzhou — in which small-scale informal lenders play a central role — suggests that the risk of nationwide financial contagion stemming from a crisis there is, for now, relatively low. For this reason, Wenzhou remains fairly unique among major Chinese cities, not only for the vibrancy of is private economy (at least until recently), but also for the comparative autonomy of its lending networks from the state-owned banking system.

Over the past decade, Wenzhou's booming real estate market has been one of the most prominent symbols of the city's highly dynamic local economy and vast private capital, built upon the city's once-prospering small and medium-sized private enterprises and entrepreneurial spirit. This made Wenzhou a central component of China's coastal low-end manufacturing sector.

But notably, as Wenzhou’s low-end manufacturing sector began to decline in the mid-2000s, the city’s property markets did not. In fact, they boomed. This boom was a result of the combination of the diversion of large sums of private capital from industrial activities into speculative markets, mostly for real estate, and a highly distorted local financing industry based on real estate mortgages, collateral and loan guarantee devices. It has been reported that among Wenzhou's top manufacturing enterprises, nearly all are involved in the real estate market.

In this context, steadily falling real estate prices in Wenzhou portend the beginning of the end for a speculative property bubble built on the back of Wenzhou's enormous pools of private capital, estimated to account for one-tenth of all private capital in China.

From 'Wenzhou model' to Bubble City

In the 1980s and 1990s, Wenzhou transformed itself from a small, densely populated and resource-scarce town into the leading city for China's nascent manufacturing economy, largely based on the strength of its cheap labor and ability to use existing family-based parts processing enterprises to position itself as the key supplier of components and parts to other emerging manufacturing bases on the coast.

The low-end, private capital-based manufacturing economic model proved enormously successful at a time when global low-end manufacturers were leaving many other countries, including South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and the United States, in response to rising input costs. The so-called Wenzhou model thus emerged as the foundation of China's more than two decades of dominance over global low-end manufacturing.

Just as local entrepreneurs accumulated large fortunes, the deficiencies of the low-end manufacturing sector inevitably emerged. Manufacturing profits were gradually eroded by rising costs and weakening external demand, especially after the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

But instead of moving up the manufacturing value chain, large private enterprises diverted much of their capital from manufacturing businesses into the higher-yield speculative economy, including the real estate market and the commodities trade. They pursued this not only as an investment strategy, but also as a financing tool to sustain their increasingly hard-pressed manufacturing enterprises' profits.

Enormous sums of private capital from Wenzhou have flowed into the local real estate market since the mid-2000s, sending local property prices skyrocketing. This model was soon emulated throughout much of coastal China, so that by the late 2000s virtually all of China's first- and second-tier cities saw their property markets boom. The impact of this shift was even felt in many overseas property markets.

At the time, the country's booming real estate market helped sustain the illusion of the successful "Wenzhou model," particularly after the 2008-2009 stimulus drive. As a result, many of the country's low-end manufacturers, which should have been phased out organically through the global economic downturn, persisted.

Local debt crises began to emerge in 2010 and 2011 as a result of a nationwide credit crunch. In Wenzhou, however, the prosperity of the city's private economy was largely sustained by flourishing informal lending networks, even after Beijing started to tighten the flow of state-backed credit to the rest of the economy. It is estimated that two-thirds of private enterprises in Wenzhou are involved in private lending markets, which take a variety of forms, from small creditors to local loan sharks. Private lending figures prominently as a vehicle for private enterprise financing — that is, lending that takes place outside of the highly restrictive state financing system.

But as private capital increasingly went into speculative property and commodities markets, informal lending activity became more and more risky. In 2010, the informal lending rate peaked at a surprising 60 per cent. The year saw many local creditors go broke, leading to widespread bankruptcies in manufacturing.

A microcosm of manufacturing transformation

While an extreme case, the painful correction the Wenzhou model is currently experiencing could be a bellwether for the enormous challenges the country is facing in its attempt to transform its manufacturing sector.

As demonstrated by the previous industrial shift, during which low-end manufacturers flocked to China, the country may soon see many of these manufacturers leave for more competitive developing economies elsewhere. Fundamentally, the declining Wenzhou model is simply a reflection of the unsustainability of low-end manufacturing, which will inevitably be affected as profit margins shrink over time.

A conversation on China's economy

In other words, the decline in low-end manufacturing is natural, but the failure to organically shift up the manufacturing value chain is not. This failure is a symptom of deep-set deficiencies in China's financial sector: namely, the restrictions on private enterprises' access to formal credit channels.

This forced more manufacturers to borrow from high-interest informal lenders, in turn compelling them to invest less in manufacturing (which was risky and had lower average returns) and more in real estate and commodities (which were booming), hence the bubble. So while the decline in low-end manufacturing was normal, it ultimately derailed into unhealthy speculative markets rather than leading to a natural climb up the manufacturing chain as it should have.

Private enterprises continued to be largely excluded from the state-dominated financial system, making the already risky informal lending sector the only viable financing channel. Additionally, investment in lucrative sectors, such as energy, resource or even high-tech was restricted to a few state-owned enterprises or through patronage networks. The shift toward speculative economies further hollowed out traditional industry, based on the anticipation of growing speculative returns.

Pilot reforms have been conducted in Wenzhou since 2011, including incremental steps toward financial liberalisation aimed at reinvigorating the city's value-added manufacturing industries and, in turn, encouraging private capital to return. So far, the real impact of these reforms appears to be limited, constrained in part by the deflation of Wenzhou's local property bubble and an overall decline in economic activity in the city.

In short, Wenzhou is a symbol for all of China. It went through the Wenzhou model phase of low-end manufacturing, but it was unable to make the transition to something more advanced. Instead, it got sucked into a real estate bubble, which in part was caused by private entrepreneurs' lack of access to cheaper credit. In a way, this is China's main problem: Its manufacturing almost reached the level of South Korea's, but at the edge of its transition up the chain, coastal China was derailed into unhealthy property markets, all due to Beijing's inability to deal with the risk of opening up the financial system. Now, five years down the road, China is dealing with the consequences.

Stratfor.com Republished with permission of STRATFOR.