It's time to talk about productivity

Of the many economic debates we have in Australia, the one we don't have is about productivity growth. It's largely ignored among the endless discussion of government debt and interest rates, house prices and the cost of living. That's unfortunate because productivity growth is the single most important factor for improving Australian living standards.

Our ability to produce more from the same number of inputs opens up a range of opportunities for Australian households and business. From more leisure time to more competitive businesses, productivity growth is often the silver bullet for so many of our economic ills.

Earlier today, the ABS released estimates for productivity growth for the 2013-14 financial year. They paint a fairly bleak picture.

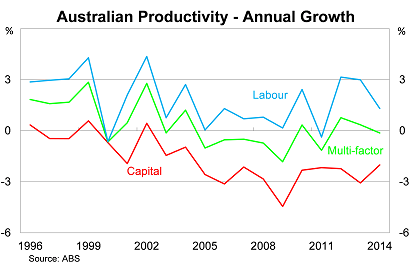

Multi-factor productivity, which measures the efficiency with which combined labour and capital inputs are transformed into outputs, fell by 0.1 per cent in 2013-14. Productivity remains lower than it was during the 1998-99 financial year.

Multi-factor productivity is comprised of two factors, labour and capital, and it is capital productivity that continues to drag down the national average. Labour productivity rose by 1.3 per cent in 2013-14, in line with its decade average, but down considerably from the 3.0 per cent growth in 2012-13.

By comparison, capital productivity fell by 2.0 per cent in 2013-14 and is down over 25 per cent since the turn of the century.

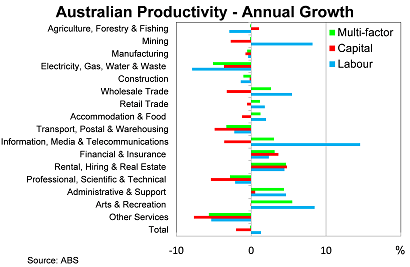

At the industry level, results were mixed. Half of the industries recorded an increase in multi-factor productivity in 2013-14. The strongest results were recorded by arts & recreation services (up 5.5 per cent); rental, hiring & real estate services (up 4.7 per cent); and administrative & support services (up 4.4 per cent).

By comparison, multi-factor productivity fell sharply in other services (down 5.7 per cent); electricity, gas, water & waste services (down 5.1 per cent); and transport (down 3.3).

Multi-factor productivity fell modestly for both mining and manufacturing. Retail posted minor gains.

Labour productivity posted some big gains in the mining and information, media & telecommunication sectors. By comparison, capital productivity was weak across most sectors, except for real estate and finance.

There are a number of points worth emphasising.

First, Australia's productivity mix presents a bit of a puzzle. The combination of dreadful capital productivity and reasonable labour productivity was once considered unusual. Now it's a feature of a number of developed countries, but unfortunately there are no satisfying answers for why this has occurred.

Broadly speaking, this may reflect a slowdown in the adoption of productivity-enhancing innovations or poor capital investment decisions at the corporate level.

To some extent, the major productivity improvements from computers and the internet were in place by the turn of the century. Although the internet and computers has improved considerably since then, internet 2.0 has been more frequently associated with productivity-sapping websites such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

Second, there are some Australian-specific drivers for this trend. For example, the sharp decline in mining productivity can be partly explained by our elevated terms of trade and the unprecedented investment response.

Due to the lag between investment and production, it's hardly a surprise that measures of productivity took a battering. As more production comes online (and as employment levels are cut), productivity growth in the mining sector will begin to turn around. That said, it's unlikely to return to its pre-boom levels.

A similar process has happened in our electricity and utilities sector. Large investments have been made to address ongoing structural challenges within the market. Supply is now more reliable than it once was but the efficiency of production hasn't necessarily improved. In other words, we are receiving a better product but it hasn't been captured by the data on productivity.

Third, it's worth noting that measuring productivity is really difficult, particularly multi-factor productivity, which is often not directly observed. We cannot discount the possibility that there are some data issues.

Fourth, the relationship between the terms-of-trade and productivity deserves some consideration. The boom in our terms-of-trade allowed income growth to exceed productivity growth, but that process works both ways. Now that our terms of trade is falling, it stands to reason that we will also experience a period where productivity growth exceeds income growth.

Finally, in the absence of higher productivity growth, wage growth will need to slow to keep inflation within the Reserve Bank's 2 to 3 per cent annual target band. The combination of high-wage growth and soft productivity is damning, particularly now that we don't benefit from a high terms of trade.

Productivity growth in Australia continues to underperform and presents a considerable challenge for the Australian economy. In the long-term, productivity determines our standard of living but in the short-term it could prove the difference between a painful terms-of-trade adjustment and a solid, vibrant economy.