In the shadow of Tiananmen, LinkedIn succumbs to China's censorship

The tentacles of Chinese censorship have extended to the US professional social media network LinkedIn on the eve of the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre. The reach of Chinese censorship is far wider than previously thought, and includes the international version of LinkedIn as well as people who are located outside of China.

That the censorship extends outside mainland China, and to English-language users of the site, is concerning -- and exceeds the measures thought necessary for LinkedIn to do business with China. For the larger business world it spotlights a significant operational risk: that the steps required to satisfy and maintain a relationship with Beijing can increase over time.

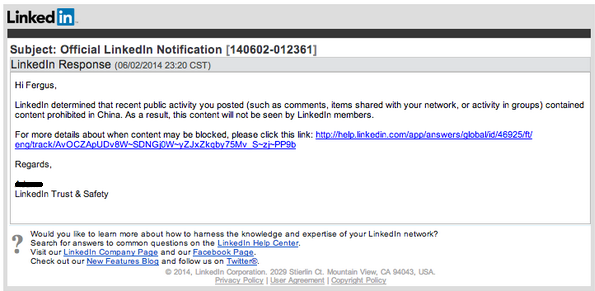

The situation was brought to the attention of your China-based correspondent when he was notified that stories he had posted on his LinkedIn account about the detention of Australian artist Guo Jian would not be seen by other LinkedIn members.

Similarly, British artist Helen Couchman, who lived in Beijing for many years, also complained about how her Linkedin posts were being censored, even though she has been based in Britain since February 2013.

“I’m very unhappy about it. I think it’s really unprofessional. Especially as I was only sharing things that are already in the public domain,” Ms Couchman told China Spectator.

“I haven’t put anything like ‘the government sucks’ or ‘it’s very, very bad behaviour’. I haven’t actually expressed my personal opinion, I’ve just shared the facts of the article. I think it’s outrageous.”

The Daily Beast also reported some Linkedin users in Hong Kong, who are usually outside of the Great Firewall of China, were also affected by the recent crackdown.

When Linkedin chief executive Jeff Weiner announced the launch of its simplified Chinese website in February, he said in a blog post that “government restrictions on content will be implemented only when and to the extent required and Linkedin will be transparent about how it conducts business in China and will use multiple avenues to notify members about our practices.”

Many thought at the time Linkedin would only censor its Chinese-language version of the professional social media network. However, in recent days, it seems Linkedin has become more aggressive in censoring user-generated China-related content.

Shaun Rein, the managing director of China Market Research, who helped Linkedin develop its China entry strategy, hasn’t been allowed to post anything on the social media network without moderation since he posted an interview he did with Bloomberg TV about IBM and the challenges it faces in China.

“LinkedIn is in a very difficult position. I’m surprised that they’re taking this action, frankly. Who is making these decisions?” he asks.

What’s happening with Linkedin is a case of self-censorship gone mad. Not only is it killing off discussion between Chinese and foreigners, it’s also affecting the ability of the international community talking to each other about developments in China. The social media site is effectively censoring content generated in China regardless of whether it comes from Chinese citizens or expatriates living there.

“We've long recognised that offering a localised version of LinkedIn in China would likely mean adherence to censorship requirements of the Chinese government on internet platforms,” LinkedIn China head of corporate communications Viola Wang told China Spectator.

"These requirements have just recently been imposed upon us within China. We are strongly in support of freedom of expression. But, as we said at the time of our launch in February, it’s clear to us that in order to create value for our members in China and around the world, we will need to implement the Chinese government’s restrictions on content, when and to the extent required."

LinkedIn is not alone in practicing self-censorship in order to gain access to the Chinese market. Last year, international financial news services company Bloomberg had to spike a number of stories that were critical of the Chinese leadership and a well-connected property tycoon, according to the New York Times.

Bloomberg infuriated Beijing authorities when it published a series of stories in 2012 on the personal wealth of the families of Chinese leaders, including the new party leader Xi Jinping. Since the publication of these stories, Bloomberg’s website has been blocked in China and its reporters have been denied long-term residency permits in the world’s second-largest economy.

Sales of Bloomberg terminals, a main source of revenue for the company, which cost $20,000 per terminal per year, have suffered. Chinese officials have told some state-owned enterprises and research institutions, such as the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, not to subscribe to terminals.

How to deal with increasingly stringent Chinese censorship regulation is a sensitive issue for foreign companies that want to operate in the world’s second-largest economy. More and more companies are willing to compromise their standards in order to gain access to the market. Linkedin’s overreach is just of one of many examples lately.

“You are only good as your last story,” said a senior Wall Street Journal editor in China, referring to the possibility of being censored in the country. Companies can do what Google did by shutting down its Chinese-language internet search in 2010 to avoid of being complicit in aiding and abetting Chinese censors. It was a brave move that few others could afford.

Bloomberg editor-in-chief Matthew Winkler highlighted the dilemma that many face in a conference call to his reporters: run these sensitive stories and get kicked out of China or practice self-censorship to stay in the game. It is an excruciating question for media executives and journalists, without an obvious answer.

Media censorship in China is more than a political issue, it is a fundamentally economic and business one as well. International investors and business people need and demand unfettered and uncensored information about the Chinese political economy and business. Governments around the world should raise this issue with Beijing to protect its own citizens as well advancing the cause of freedom in China.