How the Medibank float works against the private investor

Summary: In the Medibank Private IPO, the price will be set by an institutional bookbuild. Retail investors don't have control over the price they bid. In contrast institutional investors will be able to bid at the precise price they want to pay. |

Key take out: Retail and institutional shareholders are treated differently in the float – and it's hard for retail investors to make a buying decision when they don't know the price. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Shares. |

It has been so long since the wider public became engaged in a major government privatisation that many people have virtually forgotten the process. Moreover, the format the Abbott government has used to float Medibank Private has been greeted with much confusion and some anger. Indeed a party of 60 disgruntled policyholders have lobbied the ACCC for special treatment on the basis that policyholders, not the government, actually own the health insurer.

The controversy over the float process to some extent reveals a lack of understanding about how the market works, but for most investors it also brings up the vital question of whether private investors are being discriminated against. Today I want to study the facts.

The bookbuild process

Investors have some interesting decisions to make around participation in the Medibank Private IPO, because not only do they have to think about the value of their investment, they won't know what the price is until after they have sent in the cheques.

The official price setting mechanism is an institutional bookbuild, with investors potentially paying a price between $1.55 and $2.00 per share. Indeed, that price range only provides an “indicative range”.

While $2.00 is the highest price a retail investor can pay (the retail price cap), the final price could be lower than the $1.55 indicative minimum price.

Here is the float process:

By Friday November 14, retail investors must have sent in their applications and payments for the shares. But they must undertake to make this move while the price is unknown. There is no ability for a buyer to limit the price that they pay for shares (eg to decide only to bid for shares up to the price of $1.80 per share).

From November 18 to 20, the institutional bookbuild will happen. This will involve institutions bidding for shares. Page 121 of the prospectus outlines an interesting element of this process, stating that institutions can do this in two ways: they “may bid for shares at specific prices or at the final price”.

In other words retail investors don't get control over the price they bid.

On November 25, final pricing for Medibank shares, and allocations (scalebacks), will be announced.

If you are cynical, you might say that you will finally find out the price of something you paid for 11 days ago.

On December 1, shares will begin to trade.

Different treatment

The challenge for us as retail investors is dealing with the lack of control we have over the price.

There is no mechanism to limit the price we want to buy at.

This means that the treatment of institutional and retail shareholders is different. Institutions get to limit their bids to a set price. If, for instance, they don't want to pay more than $1.80 per share they will be able to limit their bid to that.

Retail investors have to be prepared to take whatever the final price might be up to the $2.00 ceiling, parting with their cash a week in advance of the institutional bookbuild.

This unequal treatment of shareholders could easily be improved – for example, by timing the retail investor offer so that it happens after the price has been set.

I think retail shareholders have a right to assume that all shareholders should be treated equally – after all, they are all potential part owners of the business.

Bookbuild bullies

The bookbuild price poses another hurdle for investors, especially those with hopes of a first day price premium and a quick sale. A study published in the 2013 South Asian Journal of Management, entitled ‘Determinants of IPO Pricing: An Empirical Investigation', considered the difference in performance between IPOs that had a fixed price, and IPOs that used a bookbuild (like Medibank) to set the price. They found that IPOs that used a bookbuild “command higher prices”. This is not good for buyers in an IPO, whose preference is lower prices.

Theoretically it does make sense that the price set in a bookbuild, which is set by real buyers bidding for shares, is more likely to be similar to the listing price because the process of bidding for shares is similar to what happens on the share market every day. This should provide a closer approximation of a market price when compared to a single set IPO price that has to be estimated for all buyers, and has to be considered with the motivation of setting a price low enough that there will be enough demand from investors. Unfortunately, though it's only big institutional investors that get to play in the first round of the game.

Estimating yield

In looking at the price, I think the challenging element for investors is that at $2.00 a share the value may not be that compelling.

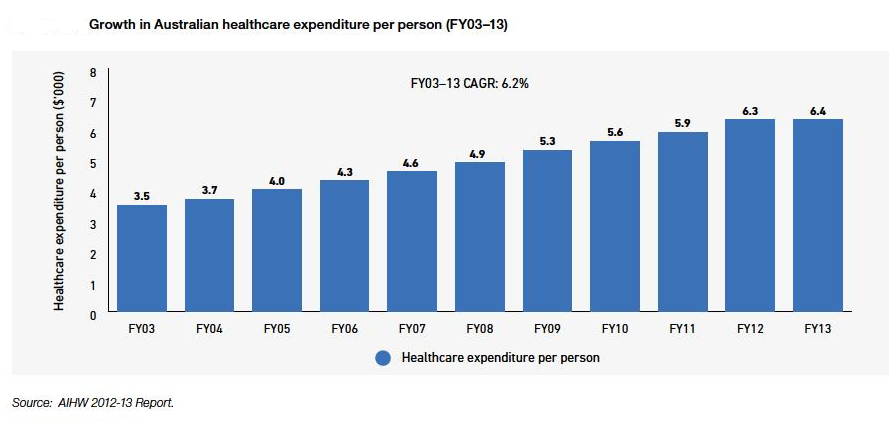

The price-earnings ratio at that price is 21.3 times earnings. This would be a relatively high multiple, mind you healthcare-related stocks achieve high multiples in our market thanks to the seemingly endless increases in health spending we have seen in Australia over the last decade (see below table from the Medibank prospectus).

If we add the dividends paid and forecast by Medibank over the 2015 financial year, being a $59 million dividend paid to the Federal Government for its ownership of Medibank for the first 5 months of the year, and the $135 million in dividends forecast for new shareholders, it comes to 7.04 cents per share.

On a share price of $2, that is a yield of 3.5%, well below the current average yield on the share market.

The prospectus talks about an implied dividend yield of 4.2%, but that is based on annualising or ‘normalising' the forecast dividends from the seven months that Medibank will be a private company.

The method I have used, adding the actual dividends paid in the 2015 financial year to the Government and then forecast for shareholders, provides a lower estimate of yield, but one that I think is worth considering seeing it is based on the actual dividends paid (see also Robert Gottliebsen's Medibank IPO first impressions: Low yielding and not cheap).

The lack of an underwriter

Another interesting observation from the prospectus is that there is no underwriter involved. The role of the underwriter is to promise that, for a fee, they will buy any shares in the IPO that are not purchased by other investors. This gives the parties selling the shares a guarantee that the shares will all be sold. This is often seen as a sign of IPO quality. A good quality IPO that is reasonably priced should have no problems finding an underwriter, giving them the guarantee of getting their float away (for a price).

The Medibank float is not using an underwriter. It might be a strategy to save on underwriter fees, and a sign of confidence that the Government thinks there will be enough demand for shares ... but for the record the float is not underwritten.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that it is tough for retail investors to know whether they want to buy an asset when then don't get to know the price until after the money has been sent in. More frustrating might be the seeming difference in treatment between institutional investors, who can bid on the basis of price, and retail investors, who are stuck with the final price, whatever it might be.

Scott Francis is a personal finance commentator, and previously worked as an independent financial adviser. The comments published are not financial product recommendations and may not represent the views of Eureka Report. To the extent that it contains general advice it has been prepared without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on it you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your objectives, financial situation and needs.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

The Medibank Private IPO is a public offering where shares of Medibank are sold to investors. Retail investors are affected because they must commit to buying shares without knowing the final price, unlike institutional investors who can bid at specific prices.

The price for Medibank shares is set through an institutional bookbuild process. Institutional investors can bid at specific prices, while retail investors must accept the final price, which could range between $1.55 and $2.00 per share.

Retail investors have less control because they cannot specify a maximum price they are willing to pay for shares. They must submit their applications and payments before the final price is determined, unlike institutional investors who can bid at specific prices.

Retail investors must submit their applications by November 14. The institutional bookbuild occurs from November 18 to 20, and the final pricing and allocations are announced on November 25. Shares begin trading on December 1.

The controversy stems from the perceived unequal treatment of retail and institutional investors. Retail investors must commit to buying shares without knowing the price, while institutional investors can bid at specific prices, leading to concerns about fairness.

The expected yield for Medibank shares is 3.5% based on a $2 share price, which is below the current average yield on the share market. The prospectus suggests an implied dividend yield of 4.2%, but this is based on annualizing forecast dividends.

The Medibank IPO is not underwritten, meaning there is no guarantee that all shares will be sold. This could indicate confidence from the government in the demand for shares, but it also means there is no safety net if demand is lower than expected.

Retail investors should consider the lack of price control, the potential yield compared to market averages, and the absence of an underwriter. It's important to assess whether the investment aligns with their financial goals and risk tolerance.