Heading for parity?

| Summary: Will the Australian dollar hit parity again this year? There are a number of reasons why the $A could continue to rise against the US dollar, especially with the domestic economy still being in pretty good shape overall. But getting to parity, and perhaps beyond, will require more than the economic status quo. And the Reserve Bank would need to tread very carefully. |

| Key take-out: A surge in the iron ore price, a marked acceleration in Chinese growth, a lift in domestic inflation, and a lift in domestic growth outcomes to well above trend rates, would be some of the factors needed for the dollar to get back to parity in the short term. |

| Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economics and investment strategy. |

Morgan Stanley created a bit of stir earlier this week after its strategy team put out a note suggesting the Australian dollar could hit parity again – sometime later this year.

I too have been bullish on the $A since late last year, and that has proven to be the right call. So I think the general gist of Morgan Stanley’s piece is right. The $A is heading higher – but will it hit parity?

As you read on, it will become clear that this is more than just a nice theoretical discussion of the $A: the difference between simply moving higher and approaching parity is material, in my view, and will have real consequences.

First things first though – could we get there? The fundamentals suggest we very easily could. There is certainly no shortage of support for the $A.

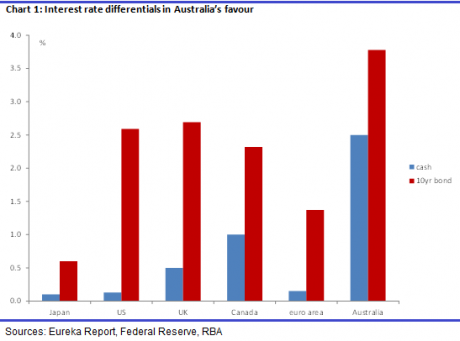

1. For a start, interest rate differentials strongly support the $A and the Reserve Bank of Australia is not printing money – unlike other major central banks around the world.

The chart above shows our 10-year bond yield is about 1% higher than the US and Britain, and a good 2.3% higher than the 10-year German bund (shown as the euro area, although there is no euro area bond). At the short-end, the official cash rate and money market rates are substantially higher in Australia at 2.5%. Canada is the closest of the major economies, with an official cash rate at 1%. Money talks: if investors need to park cash, and they do, Australia looks to be an attractive option.

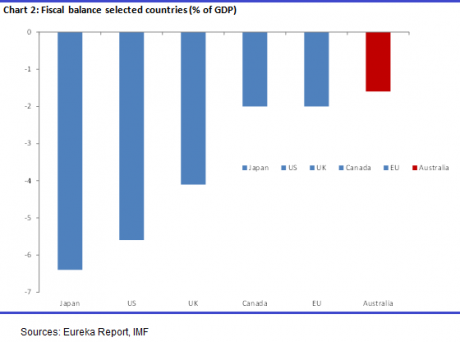

2. Australia’s fiscal balance is one of the best. That’s especially so when you consider the supposed fiscal emergency. Take a look at chart 2 below. Our fiscal balance for 2015 is expected to be around the 1% mark. Europe and Canada have a pretty good position as well, with deficits expected to be a little over 2%. But in the US, UK and Japan the situation is much worse – 3-4 times worse than Australia. Compared to those economies, Australia’s fiscal accounts are pristine.

3. That’s why Australia is one of only three countries outside of Europe with a AAA credit rating, according to Standard & Poor’s. Only 12 are ranked AAA globally. This means that Australia is a very low credit risk. Investors should, and do, love Aussie-denominated assets. Less risk, more return.

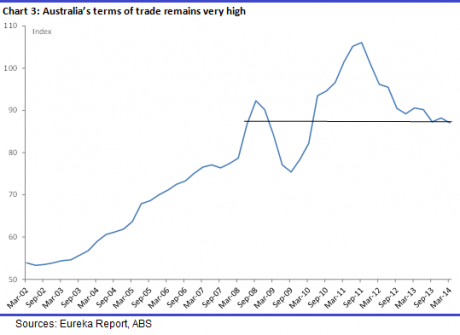

4. The terms of trade is historically very high. A lot is made of the fact that Australia’s terms of trade is declining – and it is. Yet chart 3 shows it is still at a very high level, and if you plot a simple chart of the $A and the terms of trade, it suggests the $A should be well over parity now. The rhetoric about the terms of trade reflects a much broader problem in the market however – a misunderstanding of what the terms of trade actually is. Policymakers – the Commonwealth Treasury and the RBA – seem to be particularly at fault here. Bluntly, the terms of trade is nothing – it’s a relative price index, it’s not tradable, and you can’t buy it. As a relative price, it’s meant to be an indicator of demand for Australian goods and services – of national income.

The idea is that if the terms of trade falls, this is because foreigners are buying less of our goods – export values fall relative to imports, and national income, jobs etc. suffer. That’s not what we’re seeing though, and the reason for that is simple. Price is only one determinant of income, jobs and growth. Volumes are also very important and, in our current circumstance, the decline in the terms of trade is not demand driven. That is, it doesn’t reflect a drop-off in the demand for Australian exports. On the contrary, exports are surging. In this instance then, the terms of trade is giving a misleading economic signal and policymakers have paid undue attention to it in forgetting the very significant impact of export volumes growth. That’s why they keep calling the economy incorrectly. This means that, on the theory, the fall in the terms of trade should be irrelevant for the Aussie dollar.

5. This surge in exports is why Australia has a trade surplus of about 1% of GDP. Our exports are surging despite the price falls, because demand is strong. It’s also why the current account deficit – think of it as what we have to borrow from overseas to buy imports and pay interest etc. – has shrunk sharply (to 1.4% of GDP, less than half what it was last year). The trade surplus (smaller current account deficit) shows that foreigners demand more of our goods than we do of theirs – that means, on a flow basis, there is more demand for Australian dollars, which obviously supports a higher Aussie dollar.

6. On a final note, traders now hold net long positions on the Aussie dollar: Only a month ago, traders held a net short position – that is a bet that the Aussie dollar would depreciate. Over the last few weeks that has changed markedly, and now traders are net long – a bet that the $A will continue to appreciate.

Another way of thinking about it is this. What would or could weaken the $A? From the above discussion, there isn’t a lot. Nothing just on the theory, unless the major economies start lifting rates – and they’re not going to. As we all know though, fundamentals don’t necessarily drive markets. That’s especially so for the foreign exchange market – sentiment is everything.

Noting this, I don’t think we’ll actually get to parity despite the strong support outlined above. Think about it this way. The last time the currency hit parity on upward momentum was in mid-2012. In two months, the unit moved 8%. Two factors acted as the catalyst for that – much stronger-than-expected growth and a growing view that the RBA was done cutting rates. Not too dissimilar to now, except that Chinese growth was stronger, as was the terms of trade, by about 10%. Added to that, the myth that the mining boom has ended has somehow gained significant traction, despite not being even remotely true. I think that will all help to cap $A gains.

More than that though, I don’t think there is any doubt now that if the Aussie dollar approached parity, then a rate cut would be back on the agenda – with all the confidence destroying PR that would bring. Back in 2012, the RBA’s Aussie dollar target wasn’t as explicit. The target really only became fully apparent in 2013 – well, the extent of it. In my view, this will influence sentiment; it’ll make traders more cautious to a degree, especially around what is a key psychological level. Parity will be a hard nut to crack.

To get to parity, I think we’re going to need to see more than the status quo. We know that our interest rates are attractive – investors are buying our debt. Moreover, we know exports are surging. But these flow driven influences are insignificant for a market with a turnover around $100 billion per day. So they won’t be enough, in my view. In my opinion, we’d need to see a combination of data to boost sentiment, over and above any threat the RBA would make to cut rates. This would include:

- A surge in the iron ore price.

- A marked acceleration in Chinese growth.

- A lift in domestic inflation.

- A lift in domestic growth outcomes to well above trend rates – especially from consumers.

That list isn’t exhaustive, but you get the gist. We need to see something that would render as implausible any attempt by policymakers to target the currency – or rather the rhetoric they would use. I just don’t think we are going to see that, and even if we did, I suspect the RBA would cut anyway – such is the misplaced fear over what a stronger currency would bring.

So why wouldn’t the RBA just cut if the $A continues heading high – to nip it in the bud? House prices. It’s a balancing act ultimately. I’ve stated before that the bank would start cutting if house prices moderate, and I still think that’s right. But if it looks like the $A will head above parity, I think it would cut anyway given the importance of parity to market psychology. A balancing act, as I said.