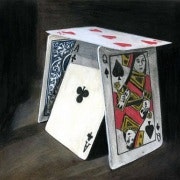

East Asia's house of cards and a North Korean joker

There are three big things going on in east Asia. The most visible and disruptive is the rise of China. The second is a resurgence, particularly in Japan, of competing and mutually reinforcing nationalisms. The third is the return of the US as a resident Asian power. Then there is the joker in the pack: the dangerous unpredictability of Kim Jong-un’s regime in North Korea.

The dynamics of, and collisions between, these trends will make the difference between war and peace in what is at once the world’s most vibrant and potentially combustible region. After a few days in Seoul listening to policy makers and scholars from the interested states, I would struggle to say I am brimming with optimism.

The Asan Institute, South Korea’s foreign policy think-tank, held its annual conference this week. It took as its theme ‘New World Disorder’. The organisers emphasised the title was chosen long before the latest nuclear sabre-rattling by Kim. Even without that menace, this region feels as strategically insecure as it is economically powerful.

It should be said, residents of Seoul do not behave as if they are living in the shadow of imminent attack. An over-excitable international media has been a lot more alarmist about an immediate threat than the residents of Seoul living within easy range of Kim’s artillery batteries. The locals have grown used to rhetorical fusillades, even if the North Korean leader seems more unstable than his predecessors. The real and deep worry is about what happens if and when Pyongyang succeeds in putting a nuclear warhead on a missile.

Given the risk of any conflict on the Korean peninsula spilling over into a wider conflagration, this should be as much of a concern to Beijing as to Seoul or Washington. And, to be fair, Chinese diplomats do not conceal their frustration with the wayward Kim. Beijing’s influence, though, has limits. Westerners who visit Pyongyang have been known to encounter as visceral a hostility towards North Korea’s Chinese paymaster as towards the US.

For now, Beijing has decided living with Kim is probably better than the most likely alternative: the complete collapse of his regime and reunification of the peninsular. That, China’s logic runs, would give the US a foothold – perhaps a military one – on its border.

Better to stick with Mr Kim, and hope he can be held in reasonable check.

It is not at all clear that this makes strategic sense. One or two voices within the Communist party elite have recently suggested that the North Korean regime has become a liability. But inaction is always easier than change, so such dissent has been silenced. For all the irritation, surrendering North Korea would risk sending a signal of weakness.

China has never clearly articulated its broader ambitions, preferring to stick with its mantra about a uniquely ‘peaceful rise’. Sharply rising defence spending, and a newly combative approach to territorial disputes with its neighbours, particularly in the South and East China seas, tells a different story. A fair-minded assessment would say its ambition is to establish political and military, as well as economic, primacy in its own backyard.

No one should be surprised by this. Regional hegemony is what great powers aim for - think of the US claim to suzerainty over the western hemisphere enunciated in the Monroe doctrine. The consequence of a more assertive Beijing, though, is suspicion and resistance among most of its neighbours. The xenophobic populism that appears across China’s blogosphere fans the embers of nationalism elsewhere. That in turn makes longstanding maritime disputes look a lot more dangerous.

One effect has been to push states such as Vietnam and the Philippines closer to the US.

In Seoul, the threat from the Beijing-backed North leads some senior politicians to suggest that Washington should consider the redeployment on the peninsula of tactical nuclear weapons. And if the North does develop a deliverable bomb, why not the South? In Japan, Shinzo Abe’s government has struck a nationalist pose that has unnerved the US and angered South Korea.

Tokyo’s disputes with Beijing over the Senkaku (known in China as Diaoyu) islands, and with Seoul over the Dokdo islands (Takeshima in Japan), have become badly entangled with an apparent revisionism on the part of Mr Abe’s government about Japan’s second world war occupations of China and Korea. Visits by senior ministers to Japan’s Yasukuni military shrine have enraged Beijing and stirred the old enmities with South Korea.

The US has been left with the problem. President Barack Obama’s much-vaunted pivot to Asia was intended to underscore the permanence of the US role as east Asia’s balancing power. The aim is to provide reassurance to Washington’s traditional allies and deter Chinese expansionism. So far, so rational, even if the strategy receives a frosty reception in Beijing. What the Obama administration now fears, however, is that Mr Abe views US treaty guarantees as a shield from behind which he can confront Beijing in the East China Sea.

So there you have it: a more assertive China, a revisionist Japan, myriad territorial disputes, angry arguments about history, and a US committed to constraining China, containing North Korea and discouraging Japan from provoking unnecessary confrontation. I have heard the architects of US policy describe this as a sustainable equilibrium. Perhaps it is my imagination, but they always seem to have their fingers crossed.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2013. Republished with permission.