Downside risks prevail in the RBA's economic outlook

The Reserve Bank of Australia is hoping that the economy transitions smoothly towards trend, but there is no shortage of factors that could cause a slip-up.

The RBA released its Statement on Monetary Policy earlier today, which showed that the outlook for the Australian economy hasn't changed over the past three months. That follows significant downgrades for both the May and August SMPs (The big question mark hanging over the RBA's outlook; August 8).

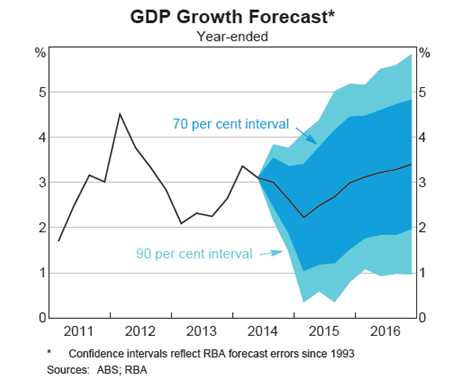

According to the RBA, the economy is set to grow at a sub-trend pace during 2015 before picking up towards around 3.25 per cent in 2016. It's important to remember that with these forecasts the confidence intervals are huge and anything beyond the next six months should be treated with a grain of salt.

In the graph below, the darker blue interval indicates that the RBA is 70 per cent confident that growth will fall within those parameters. We can also conclude that the RBA is more than 90 per cent certain that Australia will not have a recession over the next two years.

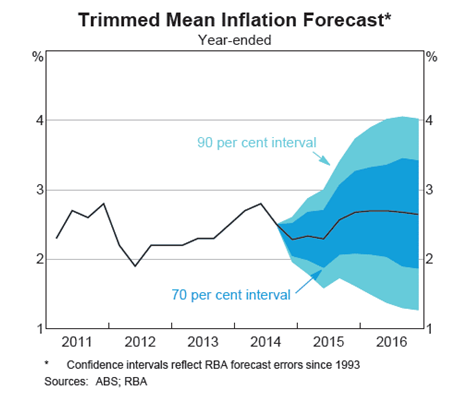

The outlook for inflation has increased slightly in the November SMP, which reflects a softer exchange rate assumption. For the purpose of the SMP, the RBA assumes that the exchange rate remains unchanged throughout the forecast horizon; at the August SMP the assumption was US93c while the new assumption is US86c.

As it stands the upgrade to inflation expectations is relatively minor and unlikely to change the RBA's existing outlook for interest rates. Nevertheless, the Australian dollar creates a considerable risk for the inflation outlook and will depend significantly on monetary policy abroad -- from the Federal Reserve raising rates next year to the Bank of Japan's unprecedented bond buying spree announced last week.

The RBA is clearly concerned that investors seeking attractive yields will look to the Australian dollar -- although I feel that concern is misplaced given the obvious structural challenges facing the Australian economy over the next few years. Personally, I believe that the effect of interest rate differentials will be swamped by weaker commodity prices.

The RBA noted that "government policy measures affected inflation in the September quarter and will continue to do so over the forecast period". The repeal of the carbon tax is "not indicative of an excess or shortfall of demand in the economy” and “[does] not have a direct bearing on monetary policy".

The RBA also provided market analysts with a handy rule of thumb for the relationship between the exchange rate, economic growth and inflation.

“Based on historical relationships, a 10 per cent depreciation of the Australian dollar (that is not associated with any further decline in commodity prices) would be expected to increase output by 0.5 - 1 per cent over a period of two years or so,” the RBA said.

“Year-ended inflation would be higher by a little less than 0.5 percentage points over each of the following two years or so.”

The risks to the outlook is always the most interesting part of the SMP. It is the one time in the entire document that you get a good feel for how the RBA is approaching its most pressing economic challenges.

This quarter it gave special mention to conditions in the Chinese housing market and their implications for the Australian resource sector. According to the RBA there are two reasons why we should be concerned about downside risks to the Chinese property sector.

First, the current downturn has been associated with slower financing growth -- partly reflecting efforts to place financing and domestic leverage on a more sustainable path. Second, there is a large overhang of property developer debt and unsold property -- I noted in an earlier article that China now has more floor space per person than Japan did prior to its property crash (There's more iron ore carnage to come; September 23).

The Chinese property sector represents a considerable financial risk for the Chinese economy. Not only is domestic debt growth rapid but citizens are buying properties at price multiples that make Sydney look like a bargain hunter's paradise.

The implications of this downturn, if it persists, is vast. Chinese residential construction relies largely on Australian iron ore production, which is expected to be a key driver of Australian economic growth over the next few years. Softer steel demand equals lower prices -- particularly as iron ore miners continue to ramp up production -- and that will hit miners and the federal budget hard.

If that sounds familiar it's because that process has already started. While the decline in iron ore prices mainly reflects supply factors thus far, Chinese authorities are trying to consolidate their steel production and ease the existing overhang of unsold properties.

On the domestic front, the biggest immediate challenge for the Australian economy remains the collapse in mining investment. The RBA once again noted that “there is uncertainty about the pace and timing of this slowing”.

It's important to remember that there is no guarantee that the rebalancing of domestic spending will be a smooth process. In fact, it would be remarkable if it was; the process could prove to be highly disruptive to the Australian economy.

What we can be sure of though is that a lot of people in the mining sector are going to lose their jobs. Estimates from ANZ and NAB from earlier this year indicate that the resource sector could cut as many as 100,000 jobs over the next couple of years.

That is particularly bad news given our economy is already finding it difficult to absorb our rapid population growth. The unemployment rate is already at a 12-year high, while the youth unemployment rate is at almost 14 per cent (A bleak jobs picture that's set to worsen; November 6).

Taken at face value the November SMP indicates that the RBA will not be lifting rates for some time. But given the elevated sense of uncertainty -- for almost every sector of the economy -- the reality is that the transition towards trend growth may not be as smooth as the RBA's forecasts indicate.

The risks to the outlook continue to lie on the downside; particularly with regard to mining investment and increasing concerns about the long-term sustainability of the Chinese property sector and its economic growth model.