Chinese medicine to stem a Japanese-style crisis

In the 1980s, Japan was widely seen as being on the cusp of overtaking the United States to become the most powerful economy in the world. Ezra Vogel, a well-known Asia scholar from Harvard University, wrote a best-selling book called Japan as Number One: Lessons for America.

The euphoria did not last long and there was a spectacular asset bubble burst, heralding the start of two lost decades. The plunging share and land prices also triggered a banking crisis in Japan; banks incurred total credit losses of $US950 billion ($A1.011 trillion) from 1992 to 2007.

This is equivalent to 105 per cent of their total profits and 285 per cent of their total capital during the same period. The Japanese government spent around $US500bn on tackling the banks’ non-performing loans problem, according to Standard & Poor’s.

There are concerns that the Chinese are going down the same pathway as the Japanese. Non-performing loans in the Chinese banking system are rising at an alarming rate following a massive expansion of credit after the global financial crisis.

Outstanding non-performing loans of 12 listed Chinese banks have increased 19.5 per cent from 390 billion yuan ($A67.27bn) to 467 billion yuan ($80.55bn) in a year, according to information disclosed in their annual reports.

A senior Chinese banking executive told Caixin that outstanding non-performing loans last year were about 100 billion yuan ($A17.25bn) but soared to 160 billion yuan ($A27.6bn) within the first two months of 2014. The Chinese banking regulator has told banks to manage their credit risk and improve their asset quality urgently.

So will the Chinese banks fall into the same trouble as their Japanese counterparts did in the 1980s? Though there are striking similarities between the Japanese situation then and the current woes of the Chinese financial system, China seems to be better prepared than Japan to handle a potential banking crisis, according to a Standard & Poor’s report, Why Chinese banks may avoid repeating Japan’s lost decade.

China’s corporate indebtedness is expected to decrease over the next few years and Beijing has already applied the brakes to the growth in runaway loans since 2011, after becoming sufficiently concerned about credit risk in its financial system.

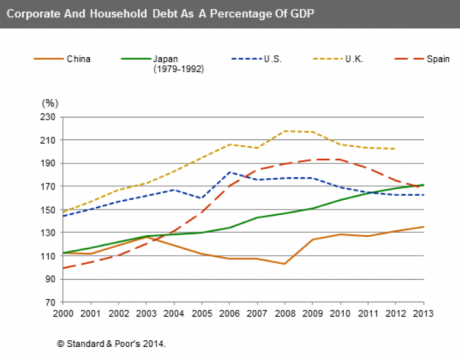

Though China has seen a massive expansion of credit in the last five years as Beijing unleashed unprecedented fiscal stimulus to counter the aftershock of the US subprime meltdown, the annual increase in the ratio of private sector credit to GDP trails the credit growth of three developed countries -- the US, Britain and Spain.

Chinese banks have strong balance sheets to withstand potential credit losses. Standard & Poor’s estimates that common equity tier one ratios of all the country’s major banks are between 9 per cent and 11 per cent, exceeding the regulatory requirement of 7.5 per cent (8.5 per cent for a systematic important bank) under Basel III.

During the heady days of the 1980s, Japan’s banking regulator failed to undertake pre-emptive steps to curb credit expansion. In comparison, Beijing is more acutely aware of the brewing problem and is taking steps to address the issue.

For example, Chinese homebuyers must cough up significant down-payments for their houses. The maximum loan to home value ratio is 70 per cent for first-home buyers and 40 per cent for second-home buyers.

The banking regulator has implemented the Basel III capital framework and also demands a higher common equity leverage ratio than the global standard.

In the early 2000s, Chinese banks’ non-performing loan ratios were as high as 40 per cent and many of them were technically insolvent. Beijing took steps to inject massive amounts of capital into these banks and provided extraordinary support. If trouble hits again, we can expect Beijing to take active measures to provide both capital and liquidity support.

In comparison, when Japanese banks faced capital shortages and credit crunches in the 1990s, the government was not able to provide prompt and decisive action, the Standard & Poor’s report shows.

China’s moderately-high GDP growth of about 7 per cent -- which is much higher than all industrialised countries and certainly much higher than the Japanese growth rate during the 1990s after the asset price crash -- is also expected to provide a buffer to the Chinese banks.

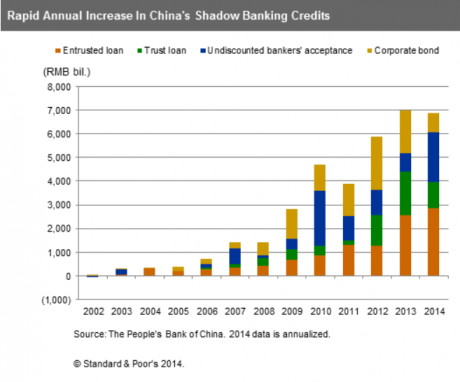

Though China is better placed than Japan to handle a banking crisis, the financial system is still expected to come under stress given the likelihood of credit losses in the shadow banking sector. “Massive defaults of shadow banking credits could trigger the failure of smaller banks with weaker financial profiles,” the Standard & Poor’s report says.

China Spectator will take a closer look at the Chinese banks’ escalating non-performing loans tomorrow.