China could deliver a double blow to Australian exports

Of the many global economic and financial trends, few are more important to Australia's long-term prosperity than the rebalancing of Chinese economic growth away from investment towards household consumption.

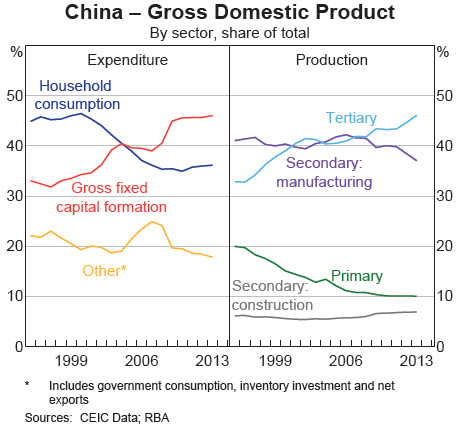

The composition of Chinese growth is odd by international standards. Investment accounts for around 46 per cent of Chinese GDP -- much higher than in developed countries where the investment share often tops out at around 20 per cent. Naturally the consumption share of GDP in China is much lower than in most other countries.

Chinese authorities have been quite open about a desire to reverse these trends. Investment of this level simply isn't sustainable in the long-run -- there's only so many houses, bridges and roads that a country has built -- and the longer investment stays at this level the greater the hole that needs to be filled later on.

A recent paper by the RBA explores this issue further, noting that “Australian exports to China consist primarily of resources, particularly iron ore and coal, and China's manufacturing sector (especially steel production) absorbs the majority of these exports”.

So what would happen if the composition of the Chinese economy shifts towards greater consumption? It's fair to say that there is a high degree of uncertainty but the World Input-Output Database offers some key insights.

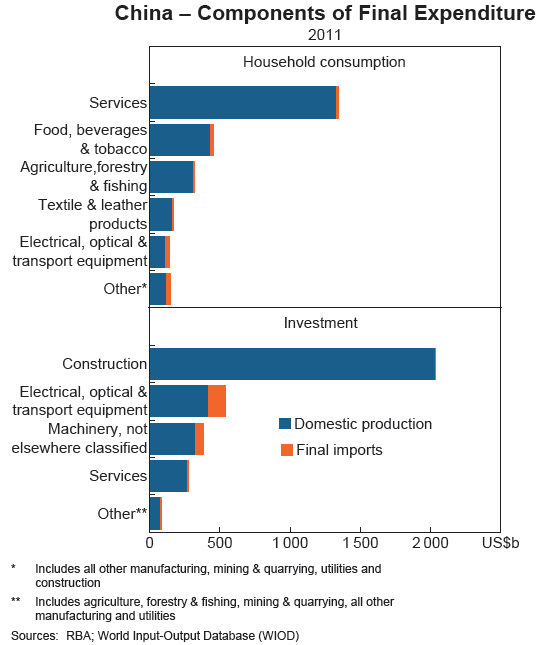

The composition of Chinese growth is contained in the graph below. Consumption is driven by services and spending on food, whereas over half of investment expenditure is captured by construction, although equipment and machinery investment is also quite high.

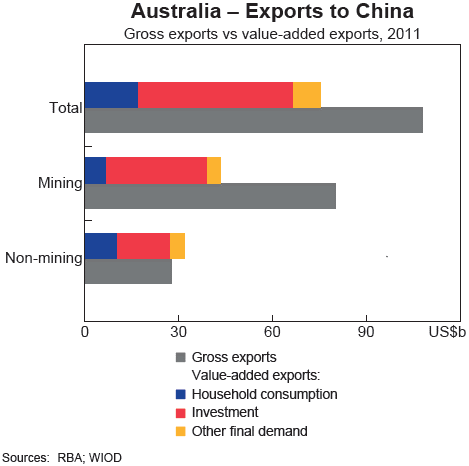

To estimate the effect of a Chinese rebalancing on Australian exports, we must draw a distinction between Australia's gross exports and ‘valued-added exports' to China. Gross exports are simply the total value of goods and services exported by Australia, whereas ‘valued-added exports' makes an adjustment for the impact of intermediate imports used in the course of production as well as Australian goods that are re-exported by China.

This distinction is covered in greater detail during an earlier article.

According to the RBA, “total Australian value-added exports to China were approximately 70 per cent of gross exports to China in 2011”. This accounts for 5 per cent of Australia's total value-added output and 27 per cent of the value-added output in the mining sector.

Chinese investment is the driver of value-added exports for both the mining and non-mining sectors. Construction has by far the highest demand for Australian value-added exports accounting for almost half the total.

In addition, it is important to emphasise that Chinese investment, particularly construction, has relatively high requirements for Australian value-added exports per dollar of output. Compared with consumption, Chinese investment is Australian exports-intensive.

This indicates that any rebalancing away from investment will weigh on the Chinese demand for Australian exports. According to the RBA, “each dollar of Chinese investment involved more than double the demand for Australian value-added output compared with each dollar of household consumption, and almost four times the demand for the Australian mining sector's value-added output.”

The table below gives a sense of the discrepancy. The numbers might seem low but remember that the Chinese economy is measured in the trillions of dollars.

The potential impact of a Chinese rebalancing on the Australian economy is considerable. If, for example, China's consumption share of GDP In 2011 was 10 percentage points higher (and investment 10 percentage points lower), Australia's GDP would be around 0.5 percentage points lower.

The RBA notes that “such a marked shift in the composition of China's growth could only be expected to happen over a number of years”. Over that time there are a range of factors -- such as changes in relative prices, including the exchange rate, and demand and supply dynamics -- that could change significantly in China and elsewhere.

As a result, the impact of a rebalancing on the Australian economy can reasonably be expected to weigh on economic growth but the extent to which is highly uncertain.

However, the expected rebalancing of the Chinese economy is several magnitudes more difficult than the one Australia is attempting to undergo. It is unlikely to be achieved without a significant slowing of growth, indicating that Australian exports will not only get hit by the compositional shift but also the slower absolute growth of the Chinese economy.

The eventual impact of this shift on the Australian economy is likely to be larger than these estimates from the RBA simply because it does not capture the sharp falls in commodity prices and the fact that most iron ore producers will go bust in the shakeout. The rebalancing of the Chinese economy necessitates a further rebalancing of the Australian economy and that has already proved to be a difficult proposition.