Buying the way out

*NB: This is the fourth article in a five-part series on designing an effective Emissions Reduction Fund. ... 1) Less talk, more action ... 2) Listening to the market ... 3) Follow the baseline.

Friday's third article on the Emissions Reduction Fund outlined some of the practical challenges facing the government as it considers baselines. In this article we consider some of the issues for abatement and the process to buy back this abatement – specifically the reverse auction.

A scheme that has a strict requirement for emissions reduction measures to be beyond business as usual, that only pays for realised abatement, will not result in any meaningful reductions in emissions.

The Direct Action plan makes it clear that it intends to fund specific projects to reduce emissions through the Emissions Reduction Fund through forward contracts. The ERF enables all businesses the opportunity to participate.

A project-based scheme brings with it a number of challenges:

1) Dealing with additionality;

2) Minimising risks that would otherwise inhibit investment in abatement measures;

3) Balancing the need for robust methodologies to prove abatement with the need for minimal regulatory burdens.

What are the sources of abatement?

The outcomes of Energetics’ webinar series show that business favours a scheme that supports all forms of abatement. This builds on the theme that the scheme be fair and equitable. Respondents were less clear on the methods used to define abatement reductions.

Two issues stood out. First, will the Clean Energy Regulator be able to validate enough methodologies to allow the fund to begin operation in 2014? Existing, approved abatement methodologies covered by the Carbon Farming Initiative and the Clean Development Mechanism provide a good starting point but still miss a range of potential sources of abatement.

In particular, the existing methodologies have limited coverage of abatement via energy efficiency measures. Energy efficiency offers cost-effective abatement, yet there is greater coverage of energy efficiency measures in the various state based energy efficiency schemes. The relationship between the ERF and the state based energy efficiency schemes emerged as an area where business is seeking further clarification and certainly projects that qualify under a state scheme, can’t in turn apply under the federally operated fund.

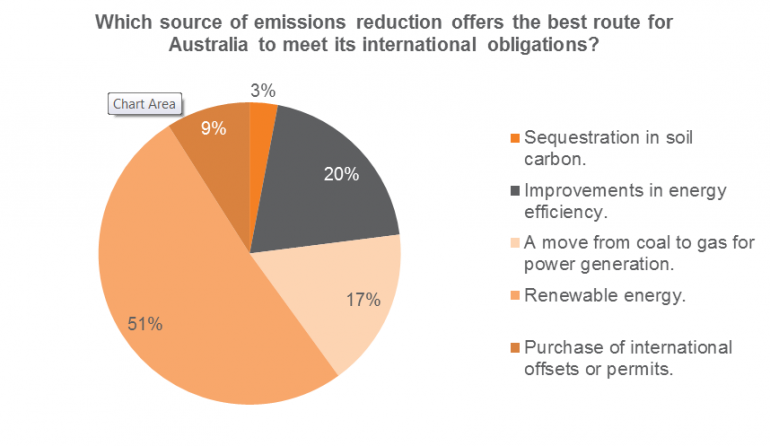

As seen in Figure 1, the clear support for renewable energy suggests that the government should consider fast tracking the development of methodologies to support renewable energy and abatement through energy efficiency. Also, the support for renewable energy further reinforces the importance of clarifying the relationship between Direct Action and the Renewable Energy Target.

Figure 1: Business feedback on the effectiveness of emissions reduction activities

The challenge of additionality

Additionality, the requirement that the emissions reduction measure be beyond business-as-usual, means that in the absence of support from the ERF, the project would not meet investment benchmarks within the business. The challenge is to demonstrate that the measure is genuinely beyond business-as-usual given every business is free to set its own financial hurdles. Also, the need to demonstrate additionality for every measure may introduce an administrative burden that will discourage businesses and especially small businesses from seeking to sell abatement to the fund.

Bringing certainty

Businesses are concerned about monitoring, verification and compliance. The proposed approach of using forward contracts to purchase abatement as it is realised provides some payment certainty. Continued uninterrupted abatement over a long-term period is hard to quantify with any certainty, and the risk of non-delivery of actual abatement is real. Further, as many abatement measures have long payback periods (for instance, the installation of renewable energy generation), businesses looking to participate in the auction process may be limited by cash flow and the need for assistance with capital expenditure.

The verification process

As discussed on Friday the fundamental aspect of baseline and credit emissions trading is the credit. The government can’t enter into forward contracts for the purchasing of abatement without a defined methodology for the abatement.

As a mechanism for providing abatement, project methodologies such as those used in the Clean Development Mechanism, the Carbon Farming Initiative and the state based white certificate schemes in Australia are generally considered to be quite robust. Historically, the process associated with creating project based methodologies is stringent and abatement will need to be independently verified prior to a methodology being approved.

The government will need to walk the fine line between ensuring that the verification process for project methodologies prior to entry into the reverse auction process is robust enough to minimise the risks of non-delivery of abatement; but not too stringent to discourage participation.

Individual project design documents will require verification to ensure that abatement claimed is achievable. To ensure a robust scheme, verification under prescribed standards, such as the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol, is essential.

Where it all comes together or falls apart – the reverse auction process

A reverse auction process differs from a straight up grant tendering process in that the government will purchase an amount of a product or service based almost solely on an assessment of its cost competitiveness. Applicants do not need to adhere to strict selection criteria as required when providing a response to a grant tender.

Using a reverse auction process to purchase tangible goods is an established market mechanism, but it is more difficult to establish for intangibles, such as emissions abatement. Failure to design contractual arrangements which provide genuine security to business prior to project implementation creates a risk that only projects which are financially viable in their own right will be subsidised by the program.

There are positives to running a reverse auction process. As a pure market-based mechanism it works to create a market signal for lowest cost abatement, as high cost abatement will not be purchased. Companies are incentivised to find the lowest cost approach to reduce their emissions profile.

How the reverse auction mechanism is framed in the final legislation will determine its effectiveness. Providing the government with monopoly rights to purchase abatement, will limit the ability of abatement trading to offset any company penalties that would exist if a baseline and credit emissions trading scheme was set up.

Also, focusing on lowest cost abatement will not drive wholesale change of the electricity generation sector which is Australia’s largest emissions source – accounting for 34 per cent of emissions in the year ending March 2013. A strong market signal is required to drive change in Australia’s current generation mix. If the government focuses on lowest cost abatement it runs the risk of playing around the edges without creating any material change.

What will this mean to businesses?

When considering the design of the ERF, new methodologies will need to be quickly developed. There will be a trade-off between breadth of abatement available to the market and a “light touch” verification process.

Implementing a strict verification process prior to including a methodology into the auction process manages the credit risk of a project, minimises the risks of non-delivery and ensures additionality. However, where the process is over complicated it may deter participation.

Conversely, where initial checks are a “light touch”, with costs for companies reduced, participation increases along with the risk of non-delivery. Here the largest risk of non-delivery is that Australia does not achieve our 5 per cent emissions reduction target through domestic abatement. The government’s Direct Action plan is committed to achieving all abatement domestically.

In our final article tomorrow we will outline a structure for the Emissions Reduction Fund that will address the concerns raised by business, as discussed in the previous parts of this series, and at the same time remain true to the principles outlined in the Direct Action plan.

Emma Fagan is a consultant and Dr Peter Holt and Gordon Weiss are both principal consultants with Energetics.