Australia's housing policy is a total con job

The Australian housing market is a mess. Decades of misguided policy -- favouring speculative gains over home ownership or affordability -- has created an intergenerational divide, which not only threatens to unravel Australia's social fabric, but is also on a collision course with history.

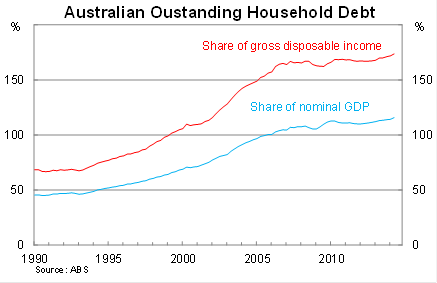

The great Australian dream is no longer achievable for most young Australians. Housing multiples are at record highs and household debt has peaked at 173 per cent of gross disposable income -- almost without peer among developed countries (Did we learn nothing from the GFC?, October 8).

A new report authored by Catherine Cashmore for Prosper Australia does an excellent job of deconstructing Australia's property market, offering simple reforms that could create a more affordable housing stock, improve government finances and ease the burden on low-income earners.

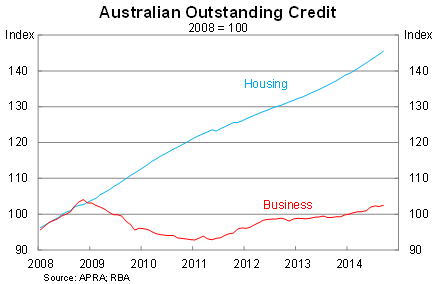

Investor activity increasingly dominates household lending in Australia. Investor loan approvals, as a share of total mortgage lending, rose to a record high of 50 per cent in September and promises to trend higher in the coming months.

Since the global financial crisis, 95 per cent of all bank lending has been channelled towards real estate -- mostly of the residential variety. Outstanding credit to owner-occupiers and investors now accounts for 60 per cent of total credit, up from 45 per cent in 2000.

That reflects the combination of historically low interest rates, a short-sighted financial system and favourable government policy. According to Prosper Australia, “investor and housing tax exemptions worth an estimated $36 billion a year have distorted the Australian dream of owning a home into a vehicle for financial speculation”.

Sadly, these billions neither increase the housing supply -- at least not materially -- nor increase the rate of home ownership. Over the past twenty years, home ownership rates have plummeted, particularly for those under the age of 45. We are increasingly a country of landlords and renters.

So what does government housing policy achieve? It is effectively an intergenerational wealth distribution vehicle that channels money from the renters (usually the young) towards existing owners (often ‘baby boomers' or older Australians).

But don't mistake Australian housing policies for benign neglect, our politicians know exactly what they are doing. Members of federal parliament have accumulated around $300 million in residential property and 94 per cent of MPs own investment properties (The conflict of interest killing housing reform, August 6).

Any reform to housing policy which benefits taxpayers and the broader business community must come at their personal expense.

According to Prosper Australia, this “means of ‘creating wealth' common in most western nations sits at the root of many of our current economic and social problems”. By redirecting income towards landowners, housing policy erodes the living standards of future generations who are required to bear increasingly high debt burdens to get into the property game.

High land prices damage Australia's competitiveness and create barriers to entry for new businesses. It burdens households with higher living costs and higher wages are needed to offset that burden (further weighing on competitiveness).

By undermining the business sector, land prices are clearly on an unsustainable course. The day of reckoning will either be Australia's next recession or the point at which a sufficient number of ‘baby boomers' decide to cash in on their investment.

The former will separate out the good investments from the bad, and property investment in Australia is increasingly negatively geared. The latter will shift market power from the rich towards younger Australians who simply can't afford existing housing multiples. We all know what happens when supply exceeds demand: prices fall.

But we need not wait for a generational shift to address affordability. According to Prosper Australia, we can start to address the housing affordability crisis by removing the accelerants that produce excessive speculative behaviour -- contained in our tax, supply and monetary policies.

According to the Henry tax review in 2010, “economic growth would be higher if governments raised more revenue from land and less revenue from other tax bases”. Land taxes are, almost without exception, the most efficient tax option available to Australian governments, instead we prefer to rely on stamp duty -- an inequitable revenue stream which promotes inefficient land use and reduces labour mobility.

Prosper Australia recommends introducing a broad-based land tax, which would create a disincentive to withhold properties from use. According to its research, in Melbourne's Docklands as much as 27 per cent of residential properties are not in active use. Vacancies are elevated in a number of inner Melbourne suburbs.

A broad-based land tax cannot be passed on to tenants and reduces the size of speculative gains. The property market suddenly places greater emphasis on finding good investments rather than gaming the tax system.

That shift should be combined with abolishing stamp duty. It's inefficient and harms labour mobility but it also creates a disincentive for people to downsize. A greater reliance on land taxes would reduce the volatility of government finances and reduce the upfront cost of purchasing a property.

Housing supply in Australia is a mess but Prosper Australia recommends creating a bond system that would recoup infrastructure levies from residents over a lengthy period of time rather than upfront. This ensures that those costs -- often significant as a share of total land prices -- are not folded into house prices.

Finally, they recommend greater investment in public housing to ameliorate household budget stress. This is preferable to rental assistance packages that enable landlords to charge higher rents than the market would otherwise bear (similar to the first home owner grant it provides minimal benefits to the recipient).

Housing policy in Australia is an absolute con job that has benefited one generation while impoverishing another. It is also clearly on an unsustainable path.

High house prices are often celebrated in Australia -- almost as a sign of our superior success -- but we ignore the inconvenient fact that sky-high house prices undermine the business sector and weigh on Australia's international competitiveness.

Property prices are not necessarily a sign of our economic success, rather a sign that state and federal governments -- combined with a compliant financial sector -- have conspired to prioritise speculative property gains over home ownership and affordable housing.

But it doesn't have to be this way and Prosper Australia have recommended a range of simple reforms that could lead to more competitive pricing and a greater supply of housing, particularly for low-income earners.

Housing affordability should be the key government issue -- an election defining issue -- but instead, it is largely ignored. Given it's the largest purchase that most individuals will ever make, the pressure should be on both state and federal governments to ensure that you aren't being ripped off.