Asia's astute offshore refuelling

Energy self-sufficiency has almost unanimously declined across Asia in the last decade, and the region’s energy appetite can only expand over the secular horizon as these economies continue to develop and standards of living rise. To meet increasing demand, many Asian oil and gas companies have not only become frequent buyers of foreign assets, they have also regularly tapped the international capital markets to meet their financing needs.

Credit investors may find numerous opportunities in Asia’s energy sector among high-quality companies with strong state support, solid fundamentals and a constructive outlook. That said, rigorous bottom-up credit research is key to identifying risks and attractive valuations.

Mounting energy shortages across Asia

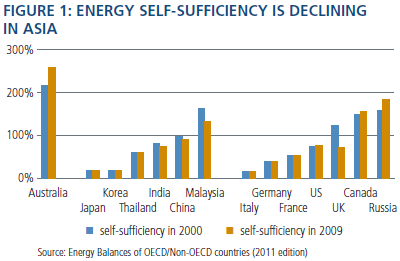

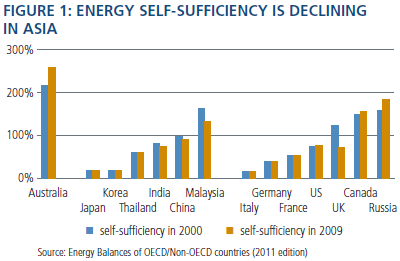

Except for Australia, which has considerable hydrocarbon reserves, most major Asian economies have seen energy self-sufficiency decline over the past decade (see Figure 1). Japan has the most pronounced energy shortage: The world’s third-largest economy is also the largest importer of liquefied natural gas, the second-largest coal importer and the third-largest oil importer. China and India have reasonable levels of natural resources, but domestic demands have rapidly outgrown production. And Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Thailand are endowed with rich natural gas reserves, but still import oil to satisfy domestic consumption needs.

The regional energy supply-demand gap is likely to widen as Asian countries shift the energy mix in favour of cleaner resources, most notably natural gas. In China, the government actively promotes natural gas in place of coal in an attempt to curb growing pollution; the target is to boost natural gas from 4 per cent of total energy use in 2011 to 8 per cent in 2015 and 12 per cent in 2020 (source: National Development and Reform Commission). And even as demand surges, Asia’s indigenous natural gas reserves face rapid decline. Thailand, for example, is already the first Southeast Asian country to import LNG, and Malaysia will shortly be opening its first LNG receiving terminal.

The mission to acquire

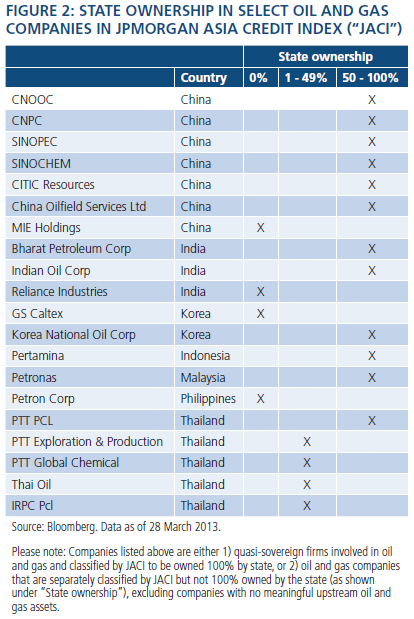

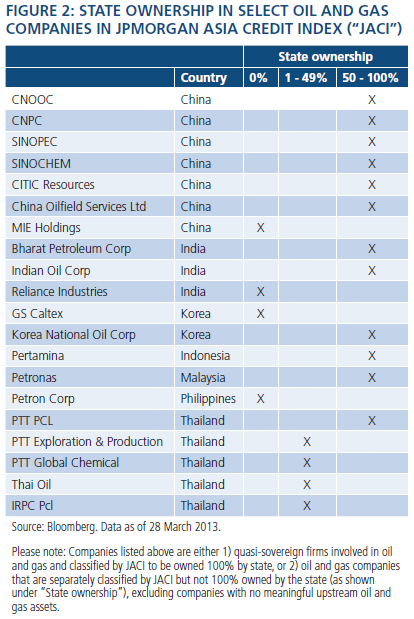

Driven by the local energy shortage, many Asian oil and gas companies are on a mission to look beyond the region for ways to enlarge their reserve base. These companies tend to have close links to the government and often participate in overseas acquisitions on the back of implicit sovereign support (see Figure 2). For example, in 2012, China’s three National Oil Companies – Sinopec, CNPC and CNOOC – announced a total of 11 overseas acquisitions, whose total value exceeded $US30 billion, according to Bloomberg data. Some transactions, such as CNOOC’s $US16.1 billion acquisition of the Canadian exploration and production firm Nexen, received heightened public and regulatory scrutiny. But this has not deterred the pace of these transactions. In the first quarter of 2013, the three Chinese NOCs have announced three more overseas acquisitions.

Amid the strong acquisition appetite, certain asset types, most notably unconventional resources in politically stable areas, appear clearly more popular than others. Many acquisition targets are located in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. For example, CNOOC’s Nexen transaction increased the OECD share of its international reserves from one-third to two-thirds. The Korea National Oil Corporation’s – KNOC's – acquisitions in the last five years are almost entirely located in the US, UK, Canada and Spain. Most Asian national oil companies have also exhibited a preference for unconventional resources such as shale gas, coal bed methane and oil sands. They are also increasingly participating in (and controlling) exploration: In February 2013, Sinopec announced it will take a 50 per cent interest in an 850,000-acre (340,000ha) Mississippi Lime exploration project operated by Chesapeake Energy. Since the transaction terms do not include drilling carry (a lump sum capital expenditure allowance for the operator), Sinopec will exercise greater control over drilling decisions and costs than other Chesapeake partners typically do on similar ventures.

The proliferation of overseas acquisitions prompts the question: What is the strategic rationale behind the buying spree? Many reports have highlighted China’s ambition to “lock up" the world’s resources. While these flashy headlines may garner attention, we question how much of the overseas production actually flows back to the country for consumption. We believe that there are other considerations at play, such as the pursuit of industry know-how and economic profits. According to the US Energy Information Administration, China has 1275 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable shale gas resources, compared with 862 trillion cubic feet in the US. Yet, in sharp contrast to the current shale boom in the US, most of China’s shale resources remain untapped due to technological limitations. But China is keen for a breakthrough: In February 2013, PetroChina and ConocoPhillips announced a collaboration to develop an approximately 500,000-acre (200,000ha) shale block in the Sichuan Basin.

Moreover, Chinese national oil companies almost unanimously face the challenge of ageing reserves and cost inflation. Sinopec’s largest domestic oilfield, Shengli, has been in production since the 1960s and has a lifting cost higher than its production fields in Angola.

The strategic importance of Asian national oil companies

The key investment thesis for Asian NOCs resides in strong sovereign support due to their strategic importance. We believe these companies perform four roles that are critical to their economies:

– Acquiring overseas assets: Most Asian NOCs are pursuing acquisitive corporate strategies, with distinct interests in unconventional assets in politically stable regions. We think these transactions not only help enlarge and diversify the current asset base, but also provide access to critical technologies that can help unlock large domestic resources. Notwithstanding the execution risks involved, we believe these acquisitive strategies point to a constructive outlook for Asian oil and gas companies.

– Managing domestic reserves: China has a meaningful 14.8 billion BOE (barrels of oil equivalent) of proven reserves as of year-end 2011. Some of the country’s largest assets such as Daqing, Shengli, and Bohai Bay have been in production since the 1960s and are still generating sizable production flows (despite some associated costs, as noted above). And Malaysia’s NOC, Petronas, manages all domestic production of the country’s significant natural gas reserves and has added a new LNG facility.

– Distributing products in domestic markets: With approximately 60 per cent and 40 per cent respective market share, Sinopec and PetroChina effectively monopolise domestic refinery product distribution. In India, three state-owned oil marketing companies, Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and HPCL, collectively control the domestic market and distribute fuel at subsidized prices.

– Executing fuel pricing policies: China aims to reform fuel price regulation, whereby CNPC and Sinopec will become the execution arms of the government’s ongoing policy changes. India has a regulated fuel subsidy program under which state-owned oil companies suffer potential losses in the form of 'under-recovery': the difference between the product discounts and government reimbursement.

In the context of high energy prices, regional shortages and growing consumption, most Asian countries have increased support to their NOCs. Korea, for example, has codified sovereign support into the 'KNOC Act', which offers direct government guarantees on KNOC’s debts and allows regular government subsidies. In Malaysia, Petronas derives its powers from the Petroleum Development Act of 1974, which vests in the company the “entire ownership in, and the exclusive rights … of exploring, exploiting, winning and obtaining petroleum whether onshore or offshore of Malaysia”.

Nevertheless, investors must be wary of the risks associated with business models that are highly dependent on sovereign support. Execution risks of aggressive mergers and acquisitions activities are certainly high. Most of Sinopec’s overseas acquisitions, for example, are performed via China Petrochemical Corp, the 100 per cent state-owned parent company. The parent company then spends considerable time and resources to “de-risk” the assets before it injects a select few into its listed subsidiary, China Petroleum and Chemical Corp.

Regulatory headwinds may also present significant challenges. Fiscal uncertainties in India have certainly set limits to its fuel subsidy program and cast valuation overhangs on the country’s state-owned oil companies.

Investment implications

We expect more Asian oil and gas companies to tap the bond market going forward, and more often. Many will likely use the proceeds to finance their overseas acquisitions and ongoing capital needs, as well as to refinance their shorter-tenor bank debt.

In light of the secular trends of energy shortages and greater overseas acquisitions, Asian governments note the critical strategic importance of their oil and gas companies, and offer them strong sovereign support. In evaluating these investment opportunities, we scrutinise the bond structure to gauge the degree of sovereign shareholder support.

We also rely on rigorous bottom-up credit research to assess risks and identify best candidates within the sector. Our general preference is for companies with large upstream assets and limited regulatory headwinds in the downstream segment. Finally, we evaluate the companies based on their standalone credit strength and ability to access alternative sources of funding. We are finding select opportunities in the Asian energy sector attractive due to both major regional trends and company-specific factors.

Raja Mukherji is an executive vice president in the Honk Kong office and head of Asian credit research for Pimco. Taosha Wang is a credit research analyst in the Hong Kong office. © Pacific Investment Management Company LLC. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.