A stronger US dollar is a double-edged sword

The United States household sector continues to struggle, but help will soon arrive in the form of a higher US dollar. A stronger dollar will increase the purchasing power of households, prompting a surge in imports, but it won't come without its risks. A higher exchange rate may also weigh on US production and, in the process, prove detrimental to the US recovery.

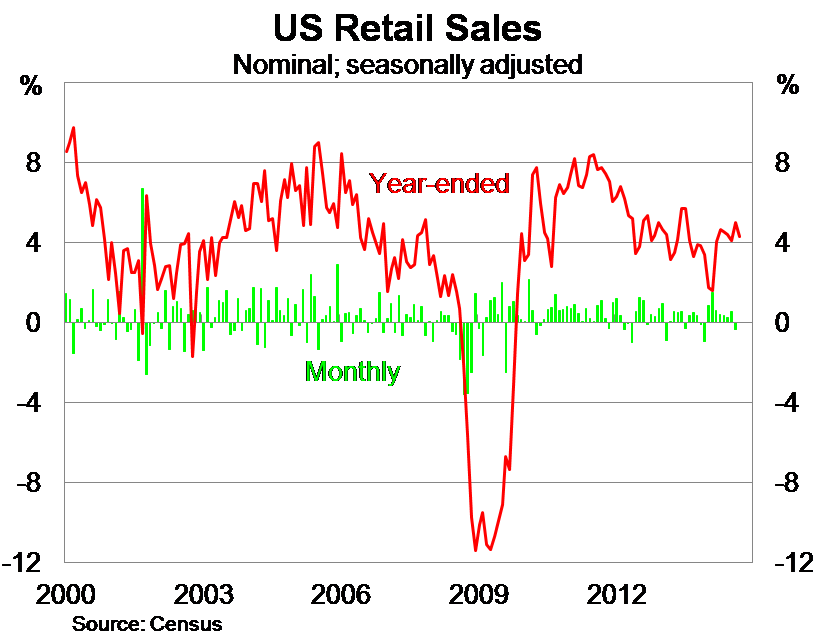

US retail sales fell by 0.3 per cent in September, missing market expectations, to be 4.3 per cent higher over the year. Household spending has been subdued throughout the September quarter and is unlikely to contribute significantly to real GDP growth.

Based on the relationship between retail sales and real household consumption, we can expect household spending to grow by around 0.3 per cent when the September quarter national accounts are released later this month.

To put that in perspective, that is around the same pace as growth during the weather-affected March quarter earlier this year. It's a significant blow for the US economy and its growth outlook, which only recently was upgraded significantly by the International Monetary Fund.

Sales of motor vehicles accounted for around half of the decline in spending during September. Motor vehicle sales were down 0.8 per cent in the month but have remained particularly strong over the past year.

Spending on building materials also declined, while the US housing market continues to concern analysts. The only major gains during September were for electronics and appliances and food services.

An interesting characteristic of the recent economic recovery and the improvement in the labour market is that is really hasn't translated into strong household spending. Over the past two years, nominal retail sales have only been growing at an annualised pace of 3.8 per cent, well below the pre-crisis trend.

One part of the story is that job growth continues to be concentrated in low-paying part-time positions. In some cases, employment is providing only modest gains over existing unemployment benefits.

Unfortunately, high-paying jobs lost during the recession have been replaced by lower-paying jobs during the recovery. According to a report by the National Employment Law Project, lower-wage sectors accounted for 22 per cent of job losses during the recession but 44 per cent of employment growth through to February this year.

Employment growth will eventually translate into higher wages and household spending, but it remains uncertain when this will occur. As spare capacity eases, businesses will need to compete to find the best talent and that will flow through to higher wage demands and eventually higher inflation.

Household spending should also receive a boost in the near to medium term by a stronger US dollar. The dollar has increased significantly against the US' major trading partners in anticipation of the Federal Reserve completing its asset purchasing program at the end of this month.

A stronger US dollar won't offer much support to US exporters, but it will increase the purchasing power of households. Expect consumption to surge as US households take advantage of a range of cheaper goods.

The obvious problem with a dollar-driven surge in household spending is that it is not clear whether the US economy wholly benefits. Sure, the purchasing power of households improves but US production may take a turn for the worse and job growth could ease. It is difficult right now to determine how susceptible the US recovery is to a change in the broader economic climate.

The recovery has proved resilient in the past: overcoming a federal government shutdown last October, the end of emergency unemployment benefits in January and the Fed's taper. On that basis, I remain reasonably optimistic about the US recovery.

But it's an optimism that is increasingly plagued by caveats, and that's a concern. The end of the Fed's asset program marks the biggest challenge yet for the US recovery and the taper tantrum experienced thus far indicates that markets do not share my optimism for US fundamentals.

How this develops over the next few weeks and months will go a long way to determining whether the Fed begins to raise rates in the first half of next year or whether they are forced to wait until 2016 (or potentially introduce a fourth round of quantitative easing).