A big hangover for water drinkers

Politicians in Queensland should be grateful they have such reassuring problems as they battle over a planned privatisation spree of $37 billion in assets.

What about infrastructure assets that have decreased in value rather than appreciated?

Over-investment in desalination plants is a case in point.

More than $10bn has already been spent on plants in Victoria, NSW, South Australia and the Gold Coast. Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane all now face two common issues: the concern that the desal plants were an unnecessary spend, and how to set water prices now that the money has been spent.

How best to recoup the cost of something that for many was clear overspend should be a matter for public debate and is in effect along the lines of other tax-collecting problems.

Some pundits argue that water users should not have to bear the brunt of the pain, and that governments should instead write down the value of these assets as corporates do, with the added bonus that this may impose a measure of discipline on future government spending.

Experts say it's hard to know which state did worst, but Victoria probably wins that title with its gold-plated desalination plant that will have cost water users $2bn by the end of June and may cost as much as $22.5bn over three decades.

With dams now more than three quarters full, no water has been drawn from Victoria's facility, which is capable of producing 150 billion litres of water a year.

You can't build a quality asset, at a reasonable cost, in a tight timeframe. Detractors say it's clear where the Victorian government chose to compromise when it contracted AquaSure amid panic over water levels prior to 2010.

Water is the cheapest commodity per tonne you will come by. It is literally cheaper than dirt per tonne, even for the best quality drinking water available.

What does cost a bomb is transporting water, and this is why there are a series of separate markets and some eyebrow-raising distortions in water pricing.

Water costs around $10 to $15 a kilolitre if trucked in, around $2 a kilolitre from the tap. Rainwater tanks, incidentally, cost around $10,000 to store a commodity only worth around $10.

But rather than charging more for water when it was in short supply, governments opted to spend big on desalination and introduce wartime-like restrictions on usage.

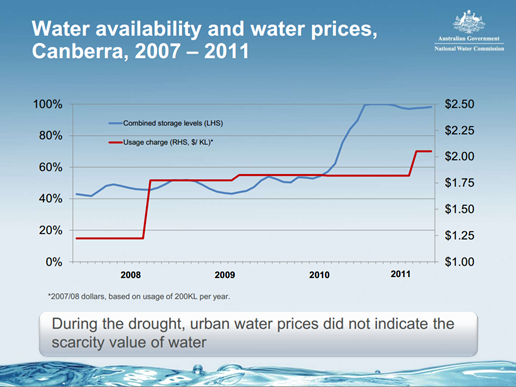

Ironically, households in urban areas in most states were previously undercharged when water was scarce, as the graph below for Canberra water use illustrates, paying much less during drought than they are today, when water is abundant.

Source: National Water Commission

Dr Richard Tooth, a director of consulting firm Sapere Research Group, says the pricing structure needs reform. In times of drought, prices should be elevated to regulate usage. Water restrictions should be about as common as food restrictions and are justifiable only at times such as the event of a major earthquake.

If fixed connection charges were reduced at the same time, the poor would be better off, he says.

If no water has been collected from the Victorian desalination plant by fiscal 2040, consumers will still have paid more than $18bn to keep the plant going. This has already helped push up average water bills in Melbourne by about $200 a year.

This may even go against the pricing principles as established by The National Water Initiative, agreed in 2004 by the Council of Australian governments, which states that water businesses should only recover efficient costs. Arguing the desal plants were an efficient spend is a tough task.

The cost of providing water varies significantly by location. Despite this, governments often opt for uniform pricing, creating a distortion and higher costs.

The NSW government's partial solution was to sell desalination for its plant to a consortium for $2.3bn, under a 50-year lease with guaranteed payments. But South Australians are paying over $3 a kilolitre for water to recoup the cost of Adelaide's 100-gigalitre-capacity desalination plant, which cost $2.2bn.

The average household water bill in South Australia has climbed to almost $800 a year from $236 in 2002.

Paul Kerin, who resigned as head of the Essential Services Commission of SA, argues South Australian households are paying up to $150 million a year too much for water based on a ‘conservative' overvaluation of the desalination plant of $2bn.

Now we have more water than we need, a lot of expensive assets that are not being used, and no political will to reform water pricing to fairly pay for the last drought and prepare for the next one.

That's an ongoing and costly challenge underscoring that what's efficient, and what's politically acceptable, are very two different things.