Is this 2008 or 2011 all over again?

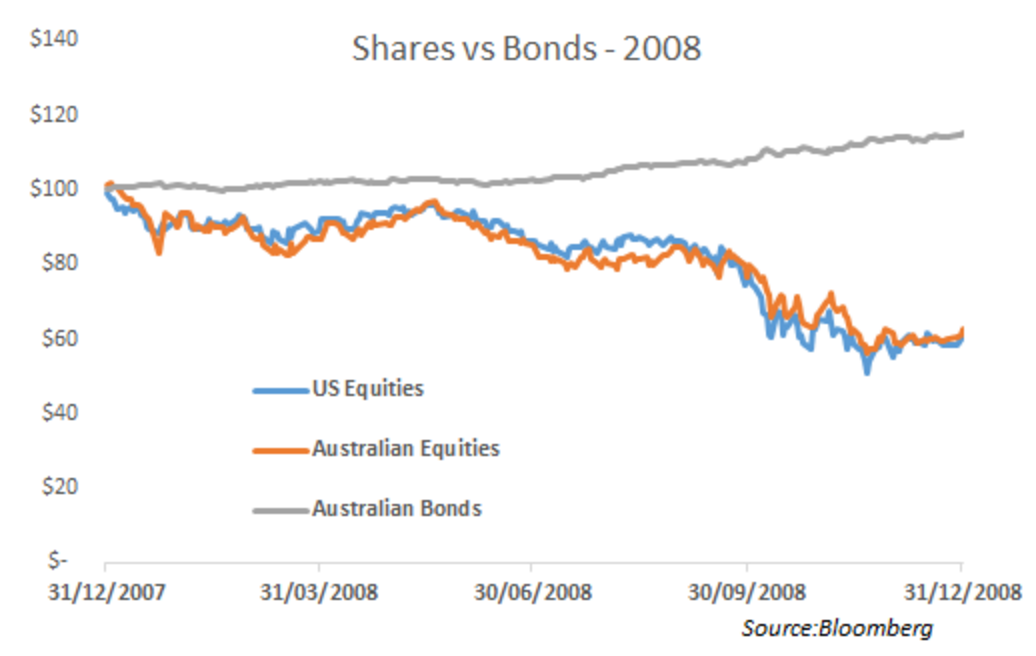

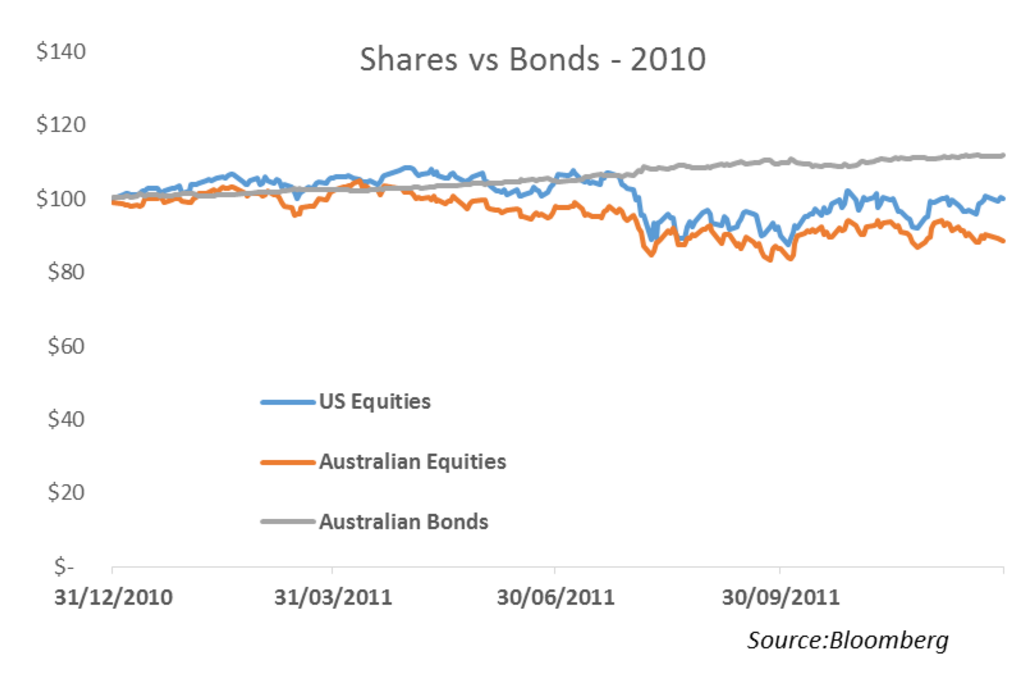

The question on the lips of panicked investors all over the world is: Will 2016 end up being a repeat of 2008 or 2011, where equities lost value? It’s enough to strike panic into the heart … but let’s not get too carried away. There was a big difference between 2008 and 2011, as you can see in the following three charts.

Clearly 2008 was a big deal — an unexpected-financial-apocalypse kind of a big deal. Share investors everywhere lost almost half their capital and it didn’t really matter much where in the world you invested. Meanwhile, bond investors made like bandits and their investment was up 15% by the end of the year.

By contrast, 2011 proved to be a bit of a blip. Aussie equity investors felt a bit hard done by as the still significant resources sector got pummelled and led the index down to a -15% fall at its worst.

The ASX finished the year 10% down while the US bounced back and finished the year flat. It would have been an overstatement to have referred to the US economy then as “resurgent” but there was definitely a sense it was the most resilient economy and market in the world. Again, bond investors made double-digit gains.

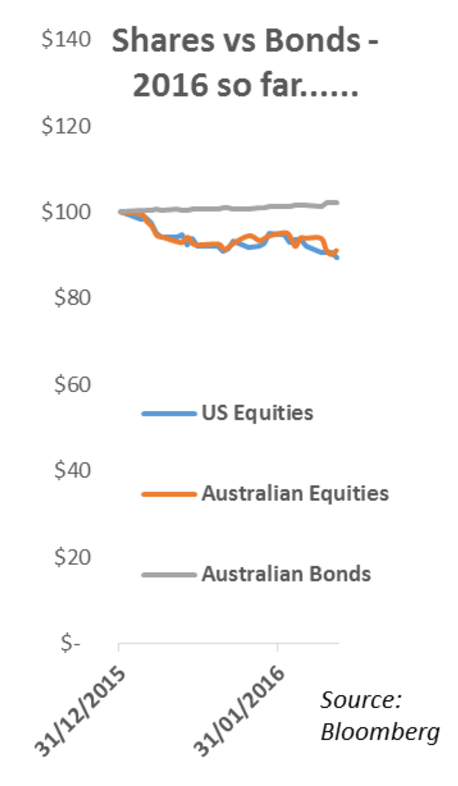

So far, 2016 has seen equity markets endure a 2011-like fall of about 10% and markets haven’t discriminated geographically. Note, though, that bonds are only up by 2% this time. With yields already so low, bonds will not be able to come to the rescue this time if 2016 ends up looking more like 2008 than 2011.

So, where to now?

The media and most pundits will focus on predicting the “things” that may or may not happen in 2016. We think you are on a bit of a hiding to nothing trying to predict this stuff. Don’t get us wrong, we take a good hard look at it — and our analysis affects the probabilities we assign to all the different scenarios. This is just not the main driver as there is a simpler and more robust starting point.

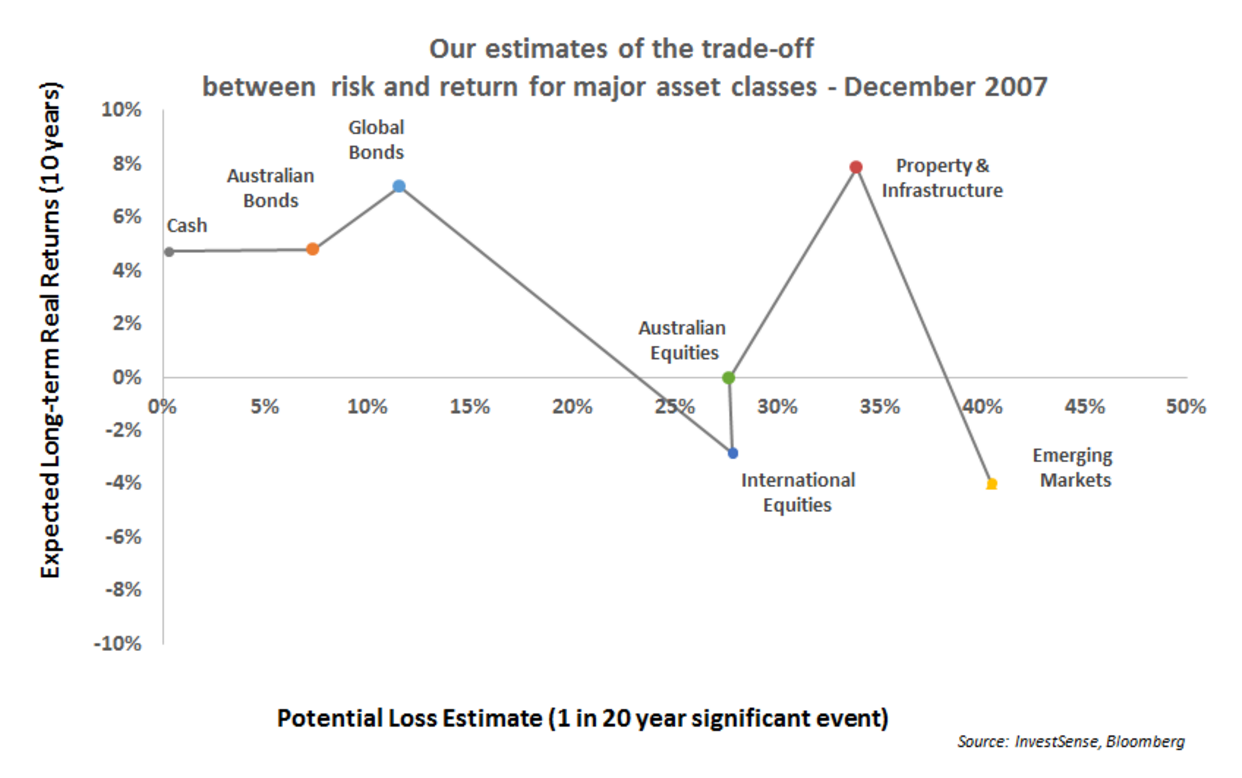

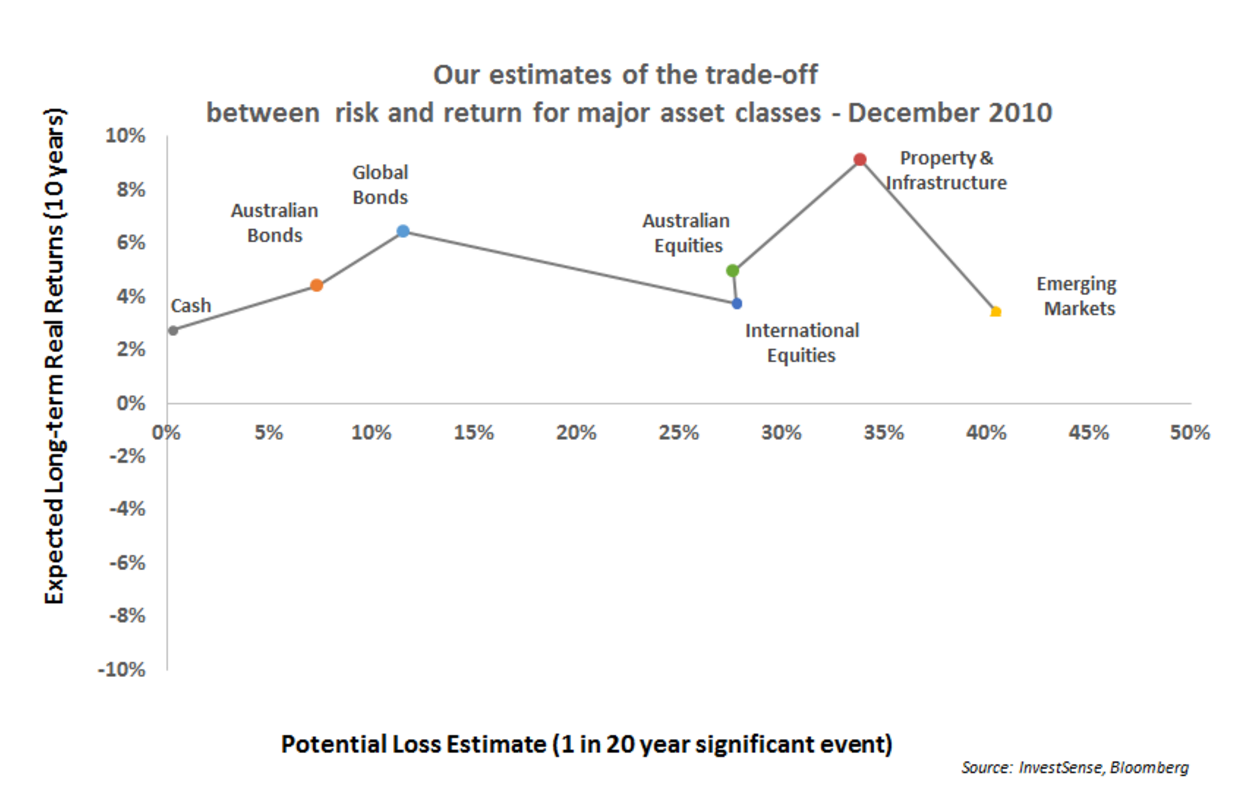

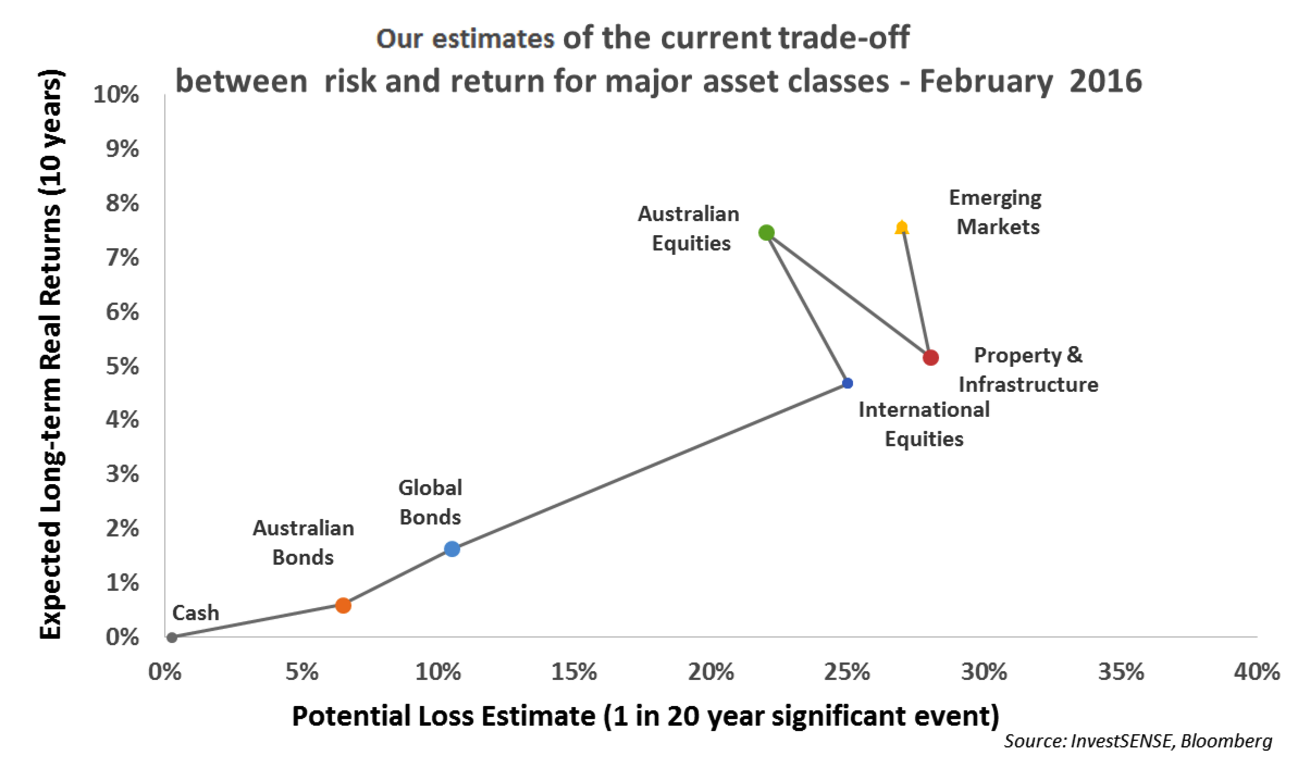

If we are really worried about how much we can make from equities and how much we might lose along the way then current valuations can tell us quite a lot about how markets might react if the unexpected happens. Recall the forward-looking risk-return line we discussed last week. The following three charts show how our Valuation Dashboard looked at the beginning of 2008, 2011 and now.

In 2007 cash rates were quite high in Australia, which ultimately provided a buffer. However, by certain metrics the long-term expected returns for most equities was actually negative. This meant that: 1) if bond rates came down then fixed income investments would do well (they did and they did), and; 2) equity investors were likely to be disappointed at some point (they were).

All that was needed was a catalyst (a US mortgage backed security and banking crisis, for instance). Some have since called this a bug looking for a windshield.

By the end of 2010, only a few years after the GFC, bond yields had come down but could still go further. Meanwhile, equity markets had risen from the GFC lows but still looked fairly valued or even a little cheap. This is indicated by the slight upwards slope of the risk-return line. So when trouble came along (the Greek debt crisis), modest falls for equities and strong returns from bonds was a reasonably predictable result.

Without the “we will do whatever it takes” speech from European Central Bank President Mario Draghi, losses may have looked more like 20% to 25%.

What about the here and now?

It is natural to assume that bonds can’t help in the way they did in 2011 and 2008, which is what we have seen so far this year. On the other hand, if there is more economic and/or geopolitical trouble ahead in 2016, falls in share markets should look more like the losses of 2011 than the sharp drop of 2008.

However, the unprecedented nature of entering a potentially recessionary environment with rates already so low means we wouldn’t rule out a further 10% to 20% fall in equities markets (especially in a low growth/higher inflation scenario). That probably won’t feel great but it may not happen — and weighed against probable returns of 5-10% per annum over the next five to 10 years we think it’s worth holding on to your equity exposure if you can stomach the volatility.

Otherwise, you need to think in terms of just holding on to the cash you have until there is a better time to buy as there are simply not a lot of other ways to make long-term gains other than through equities.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

While 2016 has seen a 10% fall in equity markets similar to 2011, the situation is not as severe as the financial crisis of 2008. Bonds are only up by 2% this time, unlike the double-digit gains seen in previous downturns, suggesting a different market dynamic.

In 2008, equity investors lost nearly half their capital, while bond investors saw a 15% gain. In contrast, 2011 was less severe, with Aussie equities down 10% and the US market finishing flat, but bond investors still enjoyed double-digit gains.

During both 2008 and 2011, bond investments provided a safe haven with significant gains. However, in 2016, bonds have only increased by 2%, indicating they may not offer the same level of protection if markets decline further.

Investors should focus on current valuations and the forward-looking risk-return line to understand potential market reactions. While predicting exact outcomes is challenging, these metrics can provide insights into possible scenarios.

With bond yields already low, there is limited room for further gains. This contrasts with past downturns where falling bond rates provided significant returns, offering a buffer against equity losses.

Equities could face a further 10% to 20% decline if economic or geopolitical issues arise. However, over the next five to ten years, equities are expected to offer probable returns of 5-10% per annum, making them a worthwhile long-term investment despite short-term volatility.

Investors should consider holding onto their equity exposure if they can handle the volatility, as long-term gains are likely. Alternatively, holding cash until a better buying opportunity arises is another strategy, given the limited options for long-term gains outside equities.

The 2008 crisis was triggered by the US mortgage-backed security and banking crisis, while the 2011 downturn was influenced by the Greek debt crisis. Both events led to significant market reactions, with bonds providing a safe haven.